The arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521 marked the beginning of a transformative era for the islands that would eventually become the Philippines. While Magellan’s initial contact was fleeting, the subsequent expedition led by Miguel López de Legazpi in 1565 firmly established Spanish dominion, initiating over three centuries of colonial rule that profoundly reshaped the archipelago’s destiny. The Spanish colonial period Philippines, lasting 333 years until the Treaty of Paris 1898, was not merely a period of foreign occupation; it was a crucible that forged a new cultural, religious, social, and political landscape. Understanding the significant legacies of Spanish rule in the Philippines is crucial to comprehending the modern Filipino nation, its identity, its strengths, and its enduring challenges. The effects of Spanish colonization Philippines were pervasive, complex, and often contradictory, leaving an indelible imprint that continues to resonate today. This article delves into these multifaceted legacies, exploring the enduring impact of Spain on Filipino religion, governance, economy, social structure, culture, language, and the very consciousness that ultimately fueled the fight for independence.

The Cross and the Crown: The Enduring Legacy of Catholicism

Perhaps the most profound and visible legacy of Spanish rule is the introduction and deep entrenchment of Catholicism in the Philippines. Prior to Spanish arrival, the islands were home to diverse indigenous belief systems, alongside pockets of Islam in the south. The Spanish saw colonization not just as a political and economic venture but as a divine mission to spread Christianity.

Conversion and Syncretism

The conversion process was rapid and widespread, driven by dedicated missionary orders (Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, Dominicans, Recollects) who often learned local languages to proselytize effectively. A key strategy employed was the Reducción policy. This involved forcibly resettling scattered indigenous populations into centralized villages built around a church and municipal hall – living bajo de la campana (“under the bell”). This facilitated easier administration, taxation, and religious instruction.

However, conversion was rarely a complete replacement of old beliefs. Instead, a unique form of folk Catholicism emerged, characterized by syncretism – the blending of indigenous spiritual practices and pre-colonial deities or spirits (anitos) with Catholic saints, rituals, and cosmology. This syncretic nature is evident in many local traditions, amulets (anting-anting), and the fervor surrounding Fiestas in the Philippines, which often incorporate pre-Christian elements alongside devotion to patron saints. Catholicism permeated daily life, structuring time around church bells, sacraments (baptism, marriage, burial), and the liturgical calendar.

The Church’s Power: Frailocracy and Social Influence

The Catholic Church, particularly the powerful friar orders, wielded immense influence far beyond the spiritual realm, a phenomenon sometimes termed Frailocracy (Frailocracia). Friars often served as the de facto rulers in local communities, overseeing not just religious matters but also education, administration, and even justice. They were significant landowners, initially benefiting from the Encomienda system (though this was technically a right to collect tribute, not land ownership) and later consolidating vast haciendas (estates).

This concentration of power led to significant abuses, including exploitation of labor, land grabbing, and interference in political affairs, which became major grievances fueling anti-colonial sentiment later on. The friars controlled much of the Education under Spain Philippines, running parochial schools and universities, shaping the curriculum, and often limiting access for the native population. Their influence permeated the Political system Philippines Spanish era, making them indispensable yet often resented figures of colonial authority.

Architectural Heritage: Baroque Churches Philippines

A tangible legacy of Spanish religious influence is the stunning collection of Baroque churches Philippines, many built during the 17th and 18th centuries. Four of these (San Agustin in Manila, Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte, Santa Maria Church in Ilocos Sur, and Miagao Church in Iloilo) are collectively designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

These churches often exhibit a unique style sometimes called “Earthquake Baroque,” characterized by massive buttresses and lower, thicker walls designed to withstand the frequent seismic activity in the region. They were not just places of worship but also served as fortifications in times of attack and became the focal points of community life, central to the Plaza complex layout. The intricate carvings and grand scale of these structures stand as testaments to the resources and religious fervor poured into establishing Catholicism.

Governance and Political Transformation

Spanish rule fundamentally altered the political landscape of the Philippines, replacing fragmented, autonomous barangays (socio-political units led by datus) with a centralized colonial state under the ultimate authority of the King of Spain, represented locally by a Governor-General in Manila.

Centralized Government and Bureaucracy

The Spanish established a hierarchical administrative structure. The archipelago was divided into provinces (alcaldías for pacified areas led by an alcalde mayor, and corregimientos for unpacified military zones led by a corregidor). Provinces were further subdivided into towns (pueblos), each headed by a gobernadorcillo (petty governor), usually drawn from the native elite or Principalía. Barangays were retained as the smallest administrative units, led by a cabeza de barangay, also from the Principalía, primarily responsible for tax collection.

This system imposed a top-down structure unfamiliar to the pre-colonial Philippines. While it created a unified political entity spanning much of the archipelago for the first time, it also entrenched a bureaucracy often characterized by corruption, inefficiency, and distance from the needs of the populace. The Political system Philippines Spanish era laid the groundwork for a centralized state but also fostered patterns of centralized power and local dependency.

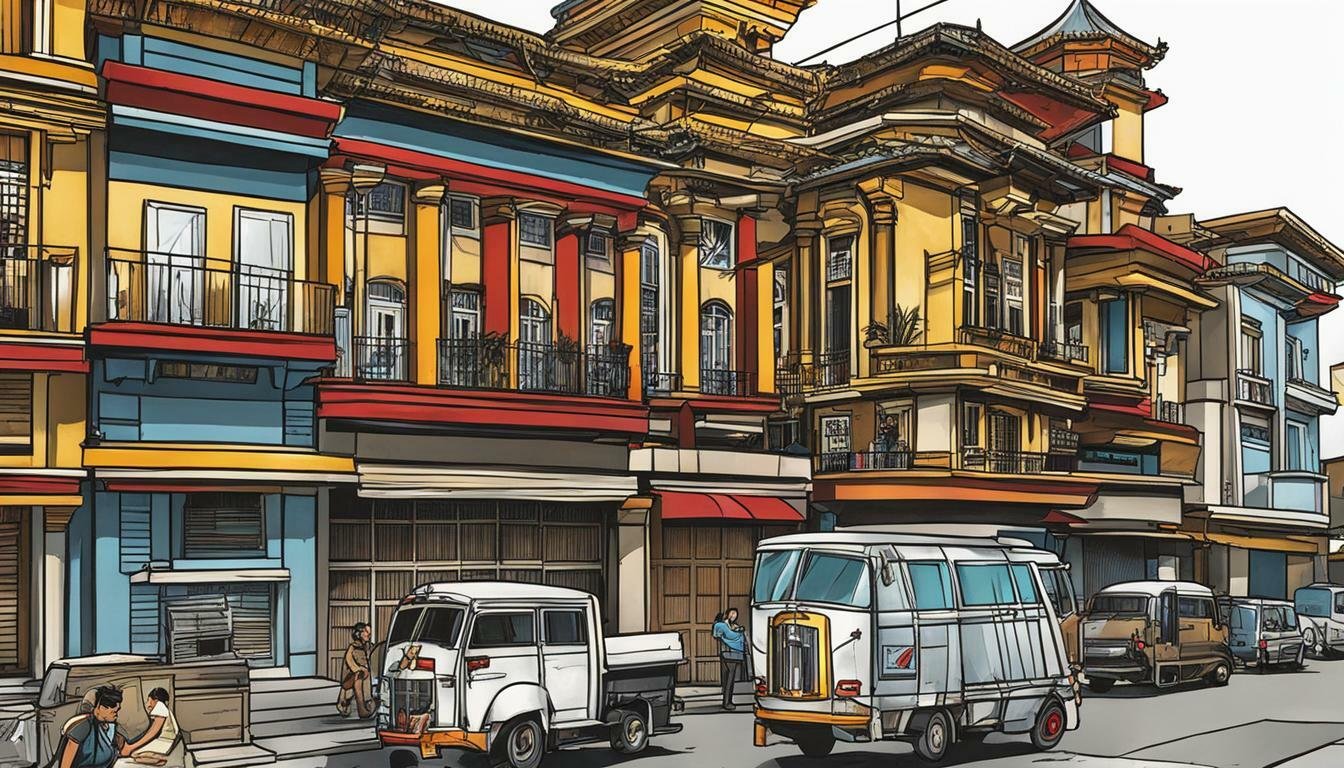

The Plaza Complex: Spatial Organization and Control

The Reducción policy was intrinsically linked to a specific urban planning model known as the Plaza complex. This layout, mandated by the Laws of the Indies, dictated that towns be organized in a grid pattern radiating from a central rectangular plaza. Dominating the plaza were the church, the convento (friar’s residence), the casa real or tribunal (municipal hall), and the residences of the local elite (Principalía).

This spatial arrangement was a powerful tool of control and acculturation. It physically manifested the twin pillars of Spanish authority – the Church and the State – placing them at the heart of community life. It facilitated surveillance, tax collection, religious observance, and the dissemination of colonial culture, reinforcing the hierarchical Social stratification Philippines Spanish era. The Plaza complex remains a defining feature of many older Philippine towns and cities.

Legal Systems and Land Ownership

Spain introduced its legal codes, significantly altering concepts of justice, property, and ownership. While customary laws persisted at the local level to some extent, Spanish law governed major aspects of life.

Land ownership underwent a dramatic transformation. The pre-colonial concept of communal land use largely disappeared, replaced by systems of private ownership and state grants favoring the colonizers and the collaborating native elite. The Encomienda system, granted to early conquistadors and settlers, gave them the right to collect tribute and demand labor from the inhabitants of a specific area in return for protection and Christian instruction. While intended to be temporary and not conferring land ownership, it often led to abuses and effective control over land and labor. Over time, this evolved into large private haciendas owned by Spanish families, religious orders, and mestizos, often acquired through royal grants, purchases, or foreclosures, dispossessing many indigenous communities and creating agrarian tensions that persist to this day.

Table: Key Stages of Spanish Governance Establishment

| Period | Key Developments | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1565 – 1600s | Establishment by Miguel López de Legazpi, Encomienda system, Reducción policy | Initial pacification, forced resettlement, tribute/labor extraction |

| 1600s – 1700s | Consolidation of central govt., Plaza complex development, Frailocracy grows | Bureaucratization, Church power increases, Manila becomes central |

| 1700s – 1800s | Rise of haciendas, Manila Galleon Trade declines, Bourbon reforms | Land concentration, economic shifts, attempts at administrative reform |

| Late 1800s | Rise of Ilustrados, Propaganda Movement, Philippine Revolution | Growing nationalism, challenge to Spanish authority, end of Spanish rule |

Export to Sheets

Economic Restructuring: Trade and Exploitation

The Spanish colonial economy was primarily extractive, designed to benefit the mother country and the colonial elite. Its most defining feature for over two centuries was the Manila Galleon Trade.

The Manila Galleon Trade (1565-1815)

This trans-Pacific trade route connected Manila with Acapulco, Mexico (then part of New Spain). Spanish galleons carried silver bullion and coin from the Americas to Manila, where it was used to purchase Asian goods like Chinese silks, porcelain, Indian textiles, and Southeast Asian spices. These goods were then shipped back to Acapulco and transported overland to Veracruz for shipment to Spain.

The Galleon Trade made Manila a thriving cosmopolitan port and a crucial node in global commerce for a time. However, its benefits were narrowly distributed, primarily enriching Spanish officials, merchants, religious orders, and Chinese intermediaries in Manila. It fostered neglect of Philippine agriculture and local industries, as colonial capital and attention were focused almost exclusively on the galleons. The economy became heavily dependent on the silver subsidy from Mexico (the situado) and the fortunes of the trade, creating a vulnerable economic structure. The walled city of Intramuros in Manila served as the administrative and commercial heart of this trade network.

Agricultural Policies and Taxation

Outside the orbit of the Galleon Trade, the rural economy was geared towards subsistence and meeting colonial demands through tribute and forced labor. The Spanish introduced new crops like corn, cacao, coffee, and tobacco, some of which became important cash crops later on.

Several exploitative systems characterized the rural economy:

- Tributo: A head tax paid by natives, initially in kind (goods) but later often demanded in cash, forcing many into debt or disadvantageous crop sales.

- Polo y Servicios: A system of compulsory rotational labor, requiring native males to work for 40 days (later reduced to 15) annually on public works projects like road and bridge construction, shipbuilding (crucial for the galleons), church building, or military service. This often took men away from their own farms during crucial planting or harvesting seasons.

- Bandala: Forced sale of local products (like rice or coconut oil) to the government at dictated, often low, prices.

- Monopolies: The government established monopolies on certain products, most notoriously tobacco in the late 18th and 19th centuries, which, while generating significant revenue for the crown, caused hardship for farmers forced to cultivate it under strict conditions.

These economic policies were major sources of discontent and fueled numerous uprisings throughout the colonial period. The effects of Spanish colonization Philippines included the creation of an economy dependent on external forces and characterized by internal inequalities.

Shaping Society: Hierarchy and Identity

Spanish rule imposed a rigid social hierarchy based largely on race and lineage, profoundly altering pre-colonial social structures. This Social stratification Philippines Spanish era became a defining feature of colonial life.

New Social Stratification

At the apex were the Peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain), who held the highest positions in government, the Church, and the military. Below them were the Insulares (Spaniards born in the Philippines, also called criollos or Creoles). Then came the Mestizos (persons of mixed Spanish and native ancestry, or sometimes Chinese and native ancestry), who occupied an intermediary position, often involved in commerce, crafts, or lower bureaucratic roles.

The vast majority of the population were the Indios (the Spanish term for the native Malay inhabitants). Within native society itself, the Spanish co-opted the existing elite, transforming the pre-colonial maginoo class into the Principalía. This group included former datus and their descendants, who were granted certain privileges (like exemption from tribute and forced labor) and served as local administrators (gobernadorcillos, cabezas de barangay). They acted as crucial intermediaries between the Spanish rulers and the native population, but their position was subordinate within the overall colonial hierarchy. At the bottom were those outside this system, including non-Christianized highland groups and Muslims in the south (often called Moros by the Spanish), who largely resisted Spanish control.

This system institutionalized racial discrimination and created deep social divisions that influenced opportunities, status, and power.

Education and the Rise of the Ilustrados

While initially focused on religious instruction and primarily accessible to Spaniards and mestizos, Education under Spain Philippines gradually expanded. The religious orders established primary schools (escuelas pías), secondary schools (colegios), and universities like the University of Santo Tomas (founded 1611).

Although access for Indios remained limited for centuries, opportunities for higher education increased somewhat in the 19th century, particularly for sons of the Principalía and wealthy mestizos. This led to the emergence of a new, educated, often European-influenced class known as the Ilustrados (“enlightened ones”). These individuals, including professionals like lawyers, doctors, and writers, became increasingly aware of liberal ideas from Europe (liberty, equality, fraternity) and the disparity between Spanish ideals and colonial realities. Figures like José Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and Graciano López Jaena were prominent Ilustrados who spearheaded the Propaganda Movement, advocating for reforms and articulating a growing sense of national consciousness.

The Concept of Filipino Identity

Ironically, Spanish colonization played a crucial role in forging a collective Filipino identity. Before 1565, the inhabitants of the archipelago identified primarily with their local communities (barangay, region, or ethnic group). Three centuries of shared experience under a single colonial power – albeit often a harsh and exploitative one – coupled with the unifying influence of Catholicism and the development of inter-regional communication and trade, gradually fostered a sense of commonality.

Initially, the term “Filipino” was used by the Spanish to refer exclusively to the Insulares (Spaniards born in the Philippines). However, by the late 19th century, the Ilustrados and later the revolutionaries began to appropriate the term for the entire native-born population, regardless of ancestry. This redefinition was a crucial step in asserting a distinct national identity opposed to the colonizers. The shared grievances against Spanish abuses, the spread of nationalist ideas, and the martyrdom of figures like José Rizal solidified this nascent identity, culminating in the Philippine Revolution.

Cultural Transformations: Language, Arts, and Daily Life

Spanish influence permeated Filipino culture, affecting language, arts, cuisine, fashion, and social customs, often resulting in unique hybrid forms.

Spanish Language Influence Philippines

While Spanish became the official language of government, education, and literature during the colonial period, it was never adopted as a lingua franca by the majority of the population. Friars often preferred to learn local languages for proselytization, and educational opportunities in Spanish were limited for most natives.

However, the Spanish language influence Philippines is undeniable, particularly in vocabulary. Thousands of Spanish words were borrowed and integrated into Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, and other Philippine languages, particularly terms related to religion, governance, cuisine, numbers, time, and abstract concepts. Spanish surnames also became widespread due to the Clavería decree of 1849, which mandated systematic adoption of surnames for easier record-keeping and taxation. Early printed materials, like the Doctrina Christiana (a catechism printed in 1593 using xylography), represent the initial intersection of Spanish language, religion, and local script/language.

Arts, Music, and Cuisine

Spanish artistic traditions heavily influenced Philippine painting, sculpture, and architecture. Religious themes dominated, with the carving of santos (statues of saints) becoming a significant folk art form. Western musical forms (like the habanera and jota) and instruments (guitar, violin, piano) were introduced and adapted, blending with indigenous musical traditions to create unique Filipino styles like kundiman.

Filipino cuisine is another area of prominent Spanish legacy, with many popular dishes having Spanish origins or names, adapted with local ingredients and flavors (e.g., adobo, menudo, lechon, paella variations, empanadas). The techniques of sautéing (guisado) and the use of ingredients like tomatoes, garlic, onions, and olive oil became staples.

Cultural Practices and Fiestas in the Philippines

The Spanish introduced numerous social customs, including forms of address, courtship practices, and emphasis on family honor. Clothing styles evolved, leading to traditional attire like the Barong Tagalog (for men) and the Maria Clara gown (for women), which combined indigenous elements with European influences.

The most vibrant expressions of Hispano-Filipino culture are arguably the Fiestas in the Philippines. Celebrated in almost every town and barrio to honor its patron saint, these events are characterized by religious processions, masses, feasting, music, dancing, and community gatherings. While rooted in Catholic tradition, fiestas often incorporate local customs and serve as vital occasions for social cohesion, hospitality, and cultural expression, embodying the syncretic nature of Filipino Catholicism. The layout of the Plaza complex often serves as the epicenter for these celebrations.

Resistance and the Seeds of Revolution

Spanish rule was not accepted passively. Resistance, both overt and covert, was a constant feature throughout the 333 years.

Early Revolts and Uprisings

From the earliest days of colonization until the late 19th century, numerous localized revolts erupted across the islands. These were often responses to specific grievances: oppressive tribute collection, forced labor (Polo y Servicios), land disputes related to the Encomienda system or haciendas, abuses by local officials or friars, or attempts to return to indigenous beliefs. Notable examples include the Tamblot Revolt (1621-22) in Bohol, the Sumuroy Rebellion (1649-50) in Samar, the Dagohoy Rebellion (1744-1829) in Bohol (the longest revolt in Philippine history), and the Silang revolts (1762-63) in Ilocos during the British occupation of Manila.

While demonstrating resilience and discontent, these early uprisings were generally localized and lacked coordination, making them vulnerable to Spanish suppression, often aided by native troops recruited from different regions.

The Propaganda Movement and José Rizal

The late 19th century witnessed a shift from localized revolts to a more organized, nationalist movement led by the Ilustrados. The Propaganda Movement (roughly 1880-1895) did not initially seek independence but advocated for reforms, demanding assimilation of the Philippines as a province of Spain, representation in the Spanish Cortes (parliament), equality before the law for Filipinos and Spaniards, secularization of parishes (transfer from friar orders to Filipino secular priests), and guarantees of basic freedoms.

José Rizal emerged as the most influential figure of this movement. His novels, Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not) and El Filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed), brilliantly exposed the injustices, corruption, and abuses of the Spanish colonial administration and the Frailocracy. While advocating for peaceful reform, Rizal’s writings awakened a profound sense of national consciousness and solidarity among Filipinos, making him a symbol of the burgeoning Filipino identity. His execution by the Spanish in 1896 galvanized widespread outrage and is considered a pivotal moment leading to revolution.

The Philippine Revolution (1896)

When it became clear that Spain was unwilling to grant meaningful reforms, a secret revolutionary society, the Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (Highest and Most Honorable Society of the Children of the Nation), or Katipunan, was founded by Andres Bonifacio in 1892. Unlike the reformist Propaganda Movement, the Katipunan aimed for complete independence through armed struggle.

The discovery of the Katipunan in August 1896 triggered the outbreak of the Philippine Revolution. Filipinos across several provinces rose up against Spanish rule. Despite internal rivalries within the revolutionary leadership and superior Spanish weaponry, the revolutionaries achieved significant successes. By 1898, they had gained control over most of the archipelago and declared Philippine independence on June 12th. However, this independence was short-lived. Following the Spanish-American War, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States in the Treaty of Paris 1898, ignoring the Filipino declaration of independence and leading to the subsequent Philippine-American War.

Ambiguous Legacies: Colonial Mentality and Enduring Issues

The legacy of Spanish rule is not monolithic; it is complex and often debated. While contributing to national unification, introducing Christianity (which remains central to Filipino identity for many), developing infrastructure, and laying foundations for modern education and governance, Spanish colonialism was also inherently exploitative and oppressive.

One frequently discussed, though controversial, concept is colonial mentality. This refers to a perceived internalized attitude of cultural inferiority among some Filipinos, characterized by a preference for foreign (particularly Western or Spanish) products, standards, and appearances over local ones. While its extent and causes are debated, some argue it stems from the hierarchical and racially conscious Social stratification Philippines Spanish era, where Spanish culture was presented as superior.

Furthermore, many contemporary issues in the Philippines have roots in the colonial past. Deep-seated socio-economic inequalities, particularly regarding land ownership, trace back to the Encomienda system and the hacienda structure. Patterns of centralized political power and local elite dominance reflect the Political system Philippines Spanish era. Even aspects of bureaucratic inefficiency or corruption can be seen as echoes of colonial administrative practices.

Evaluating the effects of Spanish colonization Philippines requires acknowledging both the contributions and the damages, the unifying forces and the divisive structures, the cultural enrichment and the economic exploitation.

Conclusion

The significant legacies of Spanish rule in the Philippines are woven into the very fabric of the nation. For over three centuries, Spain acted as a powerful catalyst, profoundly altering the religious, political, economic, social, and cultural landscape of the archipelago. The introduction of Catholicism in the Philippines, the establishment of a centralized government and the Plaza complex, the integration into global trade via the Manila Galleon Trade, the imposition of a new Social stratification Philippines Spanish era, and the pervasive Spanish language influence Philippines are among the most salient transformations.

While the Spanish colonial period Philippines brought elements that contributed to the formation of the modern nation – a unified territory, a dominant religion, shared cultural touchstones like Fiestas in the Philippines, and the eventual emergence of a national Filipino identity spearheaded by figures like José Rizal and the Ilustrados – it was also a period marked by exploitation, racial hierarchy, the abuses of Frailocracy, and the suppression of indigenous autonomy, culminating in the Philippine Revolution. The end of Spanish dominion via the Treaty of Paris 1898 did not erase these legacies; instead, they continued to shape the subsequent American period and the independent republic. Understanding these complex and often contradictory effects of Spanish colonization Philippines, including lingering issues like colonial mentality, remains essential for navigating the present and future of the Filipino nation. The baroque churches stand, the fiestas continue, Spanish words pepper daily conversation, and the deep Catholic faith endures – powerful reminders of a past that is inextricably linked to the present.

Key Takeaways

- Dominant Legacy of Catholicism: Spain’s most enduring legacy is the widespread adoption of Catholicism, deeply influencing Filipino culture, values, and traditions (Fiestas in the Philippines, Baroque churches Philippines).

- Centralized State Formation: Spain unified the fragmented archipelago under a single administration (Political system Philippines Spanish era) centered in Manila, using tools like the Reducción policy and Plaza complex.

- Economic Transformation & Exploitation: The Manila Galleon Trade integrated the Philippines into global commerce but fostered economic dependency and neglect of local development. Systems like tributo and polo y servicios exploited native labor.

- Hierarchical Social Structure: A rigid Social stratification Philippines Spanish era based on race (Peninsulares, Insulares, Mestizos, Indios) was imposed, co-opting local elites (Principalía).

- Cultural Hybridity: Spanish influence led to significant borrowing in language (Spanish language influence Philippines), arts, cuisine, and customs, creating a unique Hispano-Filipino culture.

- Forging Filipino Identity: Shared colonial experiences, the rise of the Ilustrados (José Rizal), and resistance against oppression fostered a collective Filipino identity that fueled the Philippine Revolution.

- Complex Inheritance: The Spanish legacy is ambiguous, encompassing contributions to national unity and culture alongside enduring issues stemming from colonial exploitation and hierarchy, sometimes linked to concepts like colonial mentality.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

- What was the most significant legacy of Spanish rule in the Philippines? While debatable, Catholicism in the Philippines is often cited as the most significant legacy due to its pervasive and lasting influence on Filipino culture, identity, values, and daily life for the vast majority of the population. The political unification of the archipelago under a central government is another major contender.

- Was Spanish rule entirely negative for the Philippines? No, historical analysis suggests a more nuanced view. While undeniably marked by exploitation (e.g., Encomienda system, forced labor), oppression, and racial discrimination, Spanish rule also brought elements like Christianity (valued by many Filipinos), a unified political structure, introductions in Education under Spain Philippines (leading to the Ilustrados), infrastructure development (roads, bridges, Baroque churches Philippines), new crops, and cultural exchanges (Spanish language influence Philippines, cuisine) that shaped the modern nation. Judging it requires weighing these complex effects of Spanish colonization Philippines.

- How did Spanish rule lead to the Philippine Revolution? Centuries of accumulated grievances – economic exploitation (tribute, forced labor, land issues), political disenfranchisement, abuses by the Frailocracy, racial discrimination – created widespread discontent. The failure of the peaceful Propaganda Movement led by Ilustrados like José Rizal to achieve reforms convinced many, like Andres Bonifacio who founded the Katipunan, that armed struggle was the only path to freedom, igniting the Philippine Revolution.

- Did Filipinos speak Spanish widely during the colonial era? No, widespread adoption of Spanish among the general population was limited. While it was the language of government, high society, and higher Education under Spain Philippines, missionary efforts often prioritized local languages for conversion, and access to Spanish education was restricted for most natives for much of the Spanish colonial period Philippines. However, significant Spanish language influence Philippines exists through thousands of loanwords in local languages.

- What was the Encomienda system? The Encomienda system was a grant from the Spanish Crown given to early conquistadors, officials, or settlers in the Philippines. It granted the holder (encomendero) the right to collect tribute (goods or later cash) and demand labor from the native inhabitants of a specific area. In return, the encomendero was theoretically obligated to provide protection and instruction in Catholicism in the Philippines. It was not a land grant but often led to abuses and effective control over resources and people.

- Who was Miguel López de Legazpi? Miguel López de Legazpi (c. 1502–1572) was a Spanish navigator and governor who led the expedition that established the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Philippines in Cebu in 1565. He later founded Manila in 1571, making it the capital of the Spanish East Indies. He is considered the primary figure in the establishment of Spanish colonial rule across the archipelago.

- What happened after Spanish rule ended in the Treaty of Paris 1898? The Treaty of Paris 1898 ended the Spanish-American War. In this treaty, Spain ceded the Philippines (along with Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Guam) to the United States for $20 million. This transfer ignored the Philippine Declaration of Independence proclaimed earlier that year by Filipino revolutionaries, leading directly to the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) as Filipinos fought against their new colonizers.

Sources:

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. History of the Filipino People. 8th ed., Garotech Publishing, 1990. (A foundational text in Philippine historiography).

- Constantino, Renato. The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Tala Publishing Services, 1975. (Offers a nationalist perspective on Philippine history).

- Corpuz, O.D. The Roots of the Filipino Nation. Vol. 1 & 2. AKLAHI Foundation, 1989. (Detailed socio-economic and political history).

- Phelan, John Leddy. The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700. University of Wisconsin Press, 1959. (Classic study on early Spanish cultural and religious influence).

- Schurz, William Lytle. The Manila Galleon. E. P. Dutton & Co., 1939. (The definitive work on the Galleon Trade).

- National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP): https://nhcp.gov.ph/ (Official government body for Philippine history, offers resources and articles).

- Zaide, Gregorio F., and Sonia M. Zaide. Philippine History and Government. All-Nations Publishing Co., 2004. (Widely used textbook).

- Newson, Linda A. Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press, 2009. (Examines demographic impacts of colonization).

- Rafael, Vicente L. Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society Under Early Spanish Rule. Duke University Press, 1993. (Analyzes the complexities of conversion and language).