The Philippines, a strategically vital archipelago in the Pacific, found itself thrust onto the global stage of World War II with brutal force. As a Commonwealth of the United States since 1935, it was an anticipated target for the expansionist Japanese Imperial Army. The conflict in the Philippines became a defining period in the nation’s history, marked by three tumultuous phases: the initial invasion and defense, the harsh years of Japanese occupation of the Philippines, and the bloody, destructive process of Liberation of the Philippines by Allied forces. This era forever altered the political landscape, social fabric, and national identity of the Filipino people, leaving behind a legacy of immense suffering but also inspiring tales of courage, resilience, and unwavering patriotism. Understanding the Philippines History WWII is crucial to grasping the nation’s trajectory in the 20th century and beyond.

The Gathering Storm: Pre-War Philippines and Rising Tensions

Before the bombs fell, the Philippines was on a path towards full independence from the United States, slated for 1946 under the Tydings-McDuffie Act. The Philippine Commonwealth, established in 1935 with Manuel L. Quezon as its first president, was actively preparing for self-governance. However, the escalating Japanese aggression in China and Southeast Asia cast a long shadow over these aspirations. The strategic location of the islands, bridging the gap between Northeast Asia and the resource-rich Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia), made them an indispensable piece in Japan’s vision for a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

American military presence in the Philippines, while significant, was primarily naval, centered around the base at Cavite. Ground forces, primarily the Philippine Army under development, were integrated with a smaller contingent of U.S. Army personnel to form the USAFFE (United States Army Forces in the Far East) command. This joint command was placed under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur in July 1941, a clear indication of the growing concern over Japanese intentions. Despite some efforts to bolster defenses, the Philippines remained critically vulnerable to a full-scale invasion.

The Initial Shock: Invasion and the Fall of the Philippines (1941-1942)

The Japanese assault on the Philippines began just hours after their infamous attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 (December 8 in the Philippines due to the International Date Line). Despite forewarning from Pearl Harbor, devastating air raids struck Clark Field and other bases, destroying much of the U.S. Far East Air Force on the ground. This crippled the primary defense against invasion before it could even be fully mobilized.

The Japanese Landings and Advance

Within days of the initial air attacks, Japanese invasion forces began landing on Luzon’s northern beaches. Simultaneous landings occurred in southern Luzon and Mindanao, designed to split the defending forces and secure strategic points. The speed and scale of the invasion overwhelmed the defending USAFFE troops, who were often ill-equipped, poorly trained, and spread thin across the archipelago.

General Douglas MacArthur, facing rapid Japanese advances and the destruction of his air force, made the difficult decision to implement War Plan Orange-3. This pre-war plan called for a strategic withdrawal of forces to the Bataan Peninsula, a rugged, mountainous territory ideal for defense, and the island fortress of Corregidor at the mouth of Manila Bay. The aim was to delay the Japanese advance, allowing time for reinforcements from the United States to arrive – reinforcements that, tragically, would never come in time.

The Defense of Bataan and Corregidor

The Battle of Bataan became a symbol of stubborn resistance against overwhelming odds. For over three months, Filipino and American soldiers of the USAFFE, under increasingly dire conditions, held out against relentless Japanese assaults. Facing severe shortages of food, medicine, and ammunition, and ravaged by disease, the defenders fought valiantly. The defense bought crucial time for the Allied forces elsewhere in the Pacific, delaying the Japanese timetable significantly.

Meanwhile, Manuel L. Quezon, along with Vice President Sergio Osmeña and General MacArthur, were evacuated from Corregidor to Australia in February 1942 to establish a government-in-exile, maintaining the legitimacy of the Philippine Commonwealth. Command of the remaining forces in the Philippines fell to Major General Jonathan Wainwright.

Despite their heroism, the defenders on Bataan were starving and exhausted. On April 9, 1942, Major General Edward P. King Jr., commander of the Luzon Force, surrendered the remaining USAFFE forces on Bataan to the Japanese.

The Bataan Death March: A Trail of Suffering

The surrender of Bataan was immediately followed by one of the most infamous atrocities of the war: the Bataan Death March. Tens of thousands of Filipino and American prisoners of war, many already weakened by battle, starvation, and disease, were forced to march approximately 65 miles from Mariveles, Bataan, to a prison camp at Camp O’Donnell in Capas, Tarlac.

Under the brutal supervision of the Japanese Imperial Army, the prisoners were subjected to unimaginable cruelty. They were denied food and water, beaten, bayoneted, shot for falling behind, and packed into inhumane conditions. Thousands died during the march itself, and thousands more perished in the horrific conditions at Camp O’Donnell and later at the Cabanatuan prison camp due to starvation, disease, and further abuse. The exact number of casualties remains debated, but estimates range from 7,000 to over 10,000 lives lost on the march alone. The Bataan Death March stands as a stark reminder of the war’s brutality and is a central, painful memory in Philippines History WWII.

Following the fall of Bataan, the final bastion of organized resistance was the island fortress of Corregidor. Subjected to intense aerial and artillery bombardment, the defenders on Corregidor held out for nearly another month. On May 6, 1942, with his forces decimated and facing imminent annihilation, General Wainwright reluctantly surrendered Corregidor, effectively marking the end of organized USAFFE resistance in the Philippines and the full onset of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

Life Under Japanese Occupation (1942-1945)

With the surrender of Corregidor, the Japanese Imperial Army established full control over the Philippines. The period of Japanese occupation of the Philippines was characterized by martial law, economic exploitation, and intense social upheaval. Japan’s stated goal was to incorporate the Philippines into its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, promoting Japanese culture and eradicating Western, particularly American, influence.

The Japanese Military Administration and the Second Republic

The Japanese established a military administration to govern the islands directly. They dismantled democratic institutions and imposed strict control over the population. While promising independence, their actions made it clear that any self-governance would be entirely subservient to Tokyo’s will.

In October 1943, Japan granted the Philippines nominal independence, establishing the Second Philippine Republic, often referred to as the “puppet republic.” Jose P. Laurel, a prominent pre-war politician who had remained in the Philippines, was installed as President. Laurel and other Filipino officials who served in this government faced an impossible dilemma: collaborate to mitigate the harshness of military rule and protect their people, or refuse and potentially face brutal consequences for the population. Their actions during this period remain a subject of historical debate and sensitivity in Philippines History WWII, with accusations of collaboration balanced against arguments of necessary survival and resistance from within.

Economic Hardship and Social Impact

The occupation brought severe economic hardship. The Japanese exploited Philippine resources for their war effort, seizing food, raw materials, and infrastructure. Inflation soared, and widespread shortages led to famine in some areas. Daily life was a struggle for survival.

The occupation also had a profound social impact. Curfews were enforced, freedom of speech and assembly were suppressed, and Filipinos were subjected to Japanese propaganda aimed at fostering loyalty to the Emperor and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Perhaps one of the most tragic social consequences was the institutionalization of sexual slavery through “comfort stations,” where Filipino women, known as Comfort Women, were forced to serve Japanese soldiers. This remains a deeply painful and unresolved issue.

The Brutality of Occupation

The Japanese Imperial Army ruled with extreme brutality. Suspected dissidents, guerrillas, or anyone perceived as disloyal faced torture, imprisonment, or execution. Massacres of civilians were not uncommon, particularly in areas suspected of supporting the resistance. The notorious Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, instilled widespread fear. The concept of War Crimes is inextricably linked to the conduct of the occupation forces.

The Philippine Resistance Movement (Guerrilla Warfare)

Despite the Japanese efforts to suppress dissent, the spirit of resistance among Filipinos never died. Almost immediately after the fall of Corregidor, numerous Philippine Resistance Movement groups emerged across the archipelago. These guerrilla units, composed of former soldiers, farmers, students, and ordinary citizens, became the backbone of the opposition to the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

Diverse Resistance Groups

The resistance movement was fragmented, comprising various groups with different origins, ideologies, and levels of organization. Some were remnants of the USAFFE, led by American or Filipino officers who had evaded capture (e.g., the forces under Wendell Fertig in Mindanao). Others were civilian-led groups motivated by patriotism, anti-Japanese sentiment, or local grievances.

One of the most significant resistance organizations was the Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon (People’s Anti-Japanese Army), or Hukbalahap, founded in Central Luzon. Initially a united front against the Japanese, the Hukbalahap was heavily influenced by communist ideology and drew support primarily from peasants and agricultural workers who suffered under both Japanese rule and pre-war social injustices. Their focus on land reform and peasant rights sometimes put them at odds with other, more nationalist or pro-American guerrilla groups.

The Role of Guerrillas

The guerrillas played a vital role during the occupation. They conducted sabotage operations, harassed Japanese patrols, gathered intelligence for the Allies, protected civilian populations where possible, and maintained Filipino morale. They effectively kept the flame of resistance alive, preventing the Japanese from ever achieving complete control over the countryside. The Japanese were forced to divert significant resources to counter the insurgency, weakening their overall position. The Philippine Resistance Movement was crucial in paving the way for the eventual Liberation of the Philippines.

The Tide Turns: Allied Advance and the Road to Liberation

While the Philippines suffered under occupation, the tide of World War II in the Pacific gradually began to turn in favor of the Allied Forces. Following crucial victories like the Battle of Midway, the Allies began a strategic island-hopping campaign, pushing back the Japanese perimeter. General Douglas MacArthur, having famously vowed “I Shall Return” upon leaving Corregidor, made the liberation of the Philippines a personal and strategic priority.

Allied Strategy in the Pacific

The Allied strategy involved bypassing heavily fortified Japanese strongholds while capturing strategically important islands that could serve as forward bases. By 1944, Allied forces were approaching the Philippines. The strategic importance of the archipelago lay not only in fulfilling MacArthur’s promise but also in cutting off Japan from crucial resources in Southeast Asia and providing a staging area for the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands.

MacArthur’s Return and the Leyte Landing

On October 20, 1944, after two years and seven months, General Douglas MacArthur fulfilled his promise, wading ashore at Palo, Leyte. His return signaled the beginning of the Liberation of the Philippines. Accompanying the landing force was the Philippine Commonwealth government-in-exile, returning to re-establish its authority.

The Leyte landing was preceded and covered by the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle in history. This massive engagement effectively destroyed the remaining strength of the Japanese Imperial Navy, ensuring that Japanese forces in the Philippines would be isolated and unable to receive significant reinforcements or supplies.

The Liberation Campaign (1944-1945)

The Liberation of the Philippines was a protracted and incredibly costly campaign. The Japanese garrisons, though isolated, were ordered to fight to the death, turning every island into a potential battlefield.

The Battle of Leyte

Following the initial landing, the Battle of Leyte raged for months. Japanese forces launched fierce counterattacks, including the first widespread use of kamikaze suicide pilots. Allied and Filipino forces, fighting alongside the Philippine Resistance Movement guerrillas, gradually secured the island.

The Lingayen Gulf Landings and the Drive South

In January 1945, Allied forces executed a major landing at Lingayen Gulf in northern Luzon, the same location where the Japanese had landed in 1941. This landing opened the main front for the liberation of the Philippine capital, Manila. American and Filipino forces, including recognized USAFFE guerrilla units, began their drive south.

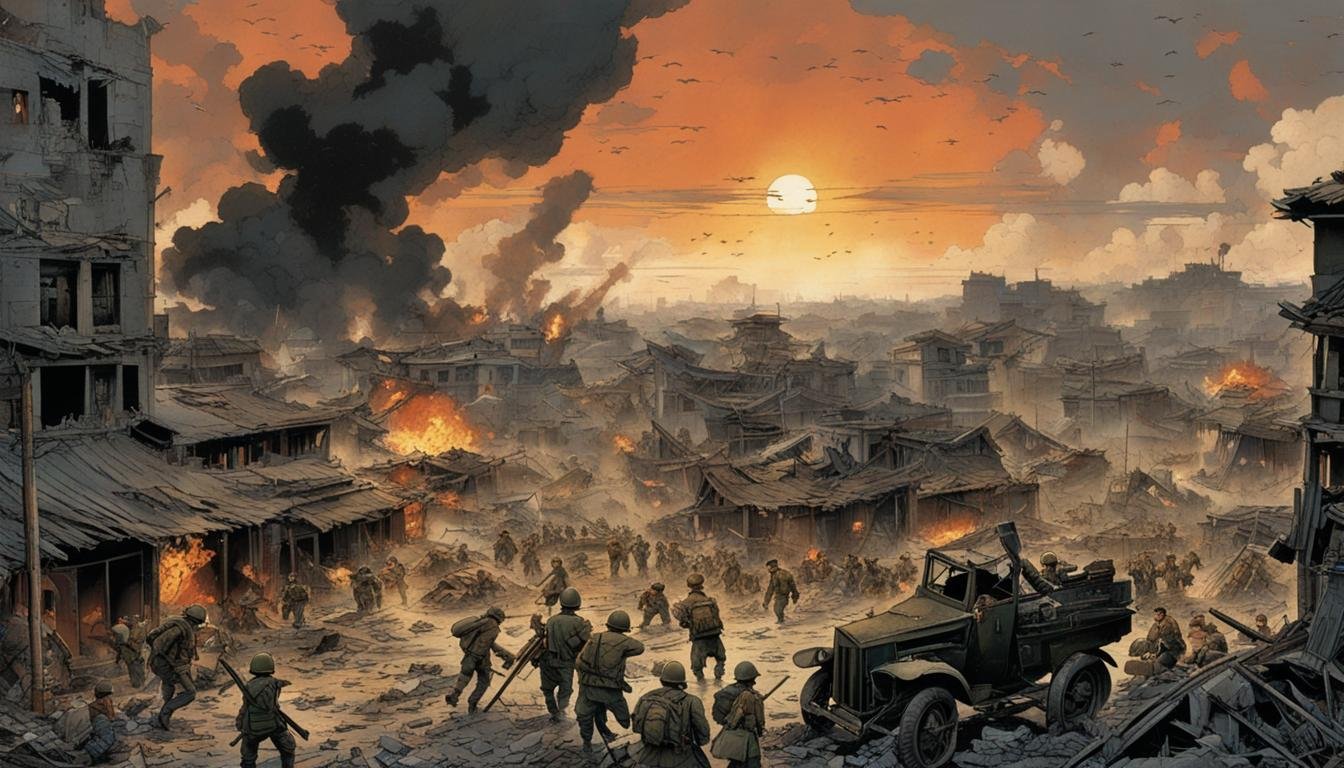

The Battle of Manila: A City Destroyed

One of the most brutal episodes of the entire war was the Battle of Manila (February-March 1945). Japanese naval forces, ordered to defend the city to the last man (despite Army command orders to withdraw), turned Manila into a killing field. They massacred an estimated 100,000 Filipino civilians in a horrific wave of brutality. The urban fighting was intense, with American artillery and aerial bombardment adding to the destruction. The beautiful, historic city of Manila was reduced to rubble, and the civilian population suffered immensely. The Battle of Manila stands as a tragic testament to the war’s impact on civilian populations.

Clearing Operations and Final Surrender

Even after the fall of Manila in March 1945, fighting continued in other parts of Luzon and on many other islands across the archipelago. Japanese holdouts, often retreating to mountainous terrain, continued resistance. The fighting gradually subsided throughout the summer of 1945.

The formal surrender of Japan on September 2, 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet declaration of war, finally brought World War II in the Philippines to an end. General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the “Tiger of Malaya” who had been placed in command of Japanese forces in the Philippines in 1944, formally surrendered to Allied forces in Baguio on September 3, 1945.

Aftermath and Legacy of World War II in the Philippines

The end of World War II in the Philippines left a nation devastated. Estimates of Filipino casualties range from 500,000 to over 1 million, making it one of the highest per capita death tolls of the war. The economy was in ruins, infrastructure was destroyed, and social scars ran deep. The experience of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines and the violent Liberation of the Philippines fundamentally shaped the country’s post-war development.

Human Cost and Destruction

The human cost was immense. Beyond the military casualties, the civilian population suffered terribly from violence, starvation, disease, and the atrocities committed during the occupation and liberation. The widespread destruction of cities like Manila left millions homeless and infrastructure in ruins. The concept of War Crimes perpetrated during the occupation led to post-war trials, including that of General Yamashita.

Political Landscape and Independence

The Philippine Commonwealth government was restored after liberation, and Manuel L. Quezon‘s successor, Sergio Osmeña, returned to lead the country. However, the war significantly impacted the political landscape. The issue of collaboration with the Japanese became a divisive one, leading to trials and political instability in the immediate post-war years.

Despite the devastation, the United States proceeded with its promise of independence. On July 4, 1946, the Philippines gained full sovereignty, becoming the independent Republic of the Philippines. The war had delayed this milestone but arguably strengthened the Filipino resolve for self-determination. The Post-war Philippines faced the daunting task of rebuilding and establishing itself as a truly independent nation.

Remembering the War

The memory of World War II in the Philippines remains vivid. Memorials across the country, such as the Mt. Samat National Shrine in Bataan and the American Memorial and Cemetery in Manila, honor the sacrifices made. The stories of the Battle of Bataan, the Bataan Death March, the courage of the Philippine Resistance Movement, and the destruction of Manila are passed down through generations, serving as powerful reminders of the horrors of war and the enduring spirit of the Filipino people.

The legacy of the war also includes unresolved issues, such as the calls for justice and reparations for Comfort Women and other victims of Japanese atrocities. The complex relationship between the Philippines, the United States, and Japan continues to be influenced by the events of this period.

World War II in the Philippines: Occupation and Liberation was a pivotal period that tested the nation to its limits. The resilience demonstrated by the Filipino people, whether fighting in the USAFFE, resisting as part of the Philippine Resistance Movement, or simply enduring the hardships of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, is a testament to their strength and determination. The costly Liberation of the Philippines ultimately secured the nation’s path to independence, but the scars of the conflict remain a significant part of its historical consciousness.

Key Takeaways:

- The Philippines was strategically important in World War II and quickly became a target for Japan after Pearl Harbor.

- The initial defense of the Philippines, including the Battle of Bataan and the Battle of Corregidor, involved combined American and Filipino forces (USAFFE).

- The surrender of Bataan led to the horrific Bataan Death March, a major Japanese War Crime.

- The Japanese occupation of the Philippines was marked by harsh military rule, economic exploitation, and the establishment of a puppet government under Jose P. Laurel.

- A strong and diverse Philippine Resistance Movement (guerrilla warfare), including groups like the Hukbalahap, actively fought against the Japanese throughout the occupation.

- The Liberation of the Philippines began with Douglas MacArthur‘s return to Leyte in October 1944, following the decisive Battle of Leyte Gulf.

- The Liberation Campaign was brutal, culminating in the devastating Battle of Manila, where widespread atrocities were committed against civilians.

- The war had a catastrophic human and economic cost but paved the way for Philippine independence in 1946.

- The legacy of World War II in the Philippines continues to influence the nation’s memory and international relations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

Q1: Why was the Philippines so important to Japan during World War II? A1: The Philippines was crucial due to its strategic location. Controlling the islands would cut off vital supply lines between the United States and its allies in Southeast Asia, and it provided a necessary stepping stone for Japan to access the resource-rich territories further south, fitting into their plan for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Q2: What was the significance of the Battle of Bataan? A2: The Battle of Bataan was significant because the Filipino and American defenders of USAFFE held out against the Japanese for over three months. This significantly delayed the Japanese timetable for conquest in the Pacific, buying crucial time for the Allies to reorganize and build up their forces elsewhere, even though it ultimately ended in surrender and the tragic Bataan Death March.

Q3: Who was Douglas MacArthur and what was his role in the Philippines during WWII? A3: Douglas MacArthur was the commander of the USAFFE forces at the start of the war. He initially directed the defense of Bataan and Corregidor but was ordered to leave the Philippines. He famously vowed “I Shall Return” and led the Allied forces in the Pacific theater. He spearheaded the Liberation of the Philippines, returning to Leyte in 1944 and overseeing the campaign that ended the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

Q4: What was the Hukbalahap? A4: The Hukbalahap was one of the largest and most effective groups within the Philippine Resistance Movement. It was founded in Central Luzon and fought against the Japanese occupiers. While initially a broad anti-Japanese front, it was heavily influenced by communist ideology and championed peasant rights, which led to conflicts with other resistance groups and the post-war Philippine government.

Q5: What happened during the Battle of Manila? A5: The Battle of Manila was the fight for the Philippine capital in February and March 1945. It was one of the most devastating urban battles of the war. Japanese naval forces, ordered to defend the city, committed horrific atrocities against Filipino civilians, resulting in the massacre of an estimated 100,000 people. The intense fighting also resulted in the near-total destruction of the city.

Q6: How did the Japanese occupation impact the average Filipino citizen? A6: The Japanese occupation of the Philippines had a devastating impact on average Filipinos. They experienced severe economic hardship, including food shortages and hyperinflation. Basic freedoms were suppressed under martial law, and civilians lived under constant fear of the Japanese Imperial Army and the Kempeitai. Many suffered from lack of food, medicine, and basic necessities, while women were subjected to forced prostitution as Comfort Women.

Q7: When did the Philippines gain independence after the war? A7: The Philippines gained full independence from the United States on July 4, 1946. World War II in the Philippines had delayed the original independence schedule set for 1946 under the Tydings-McDuffie Act, but the process went forward shortly after the war’s end.

Q8: What is the significance of the Bataan Death March today? A8: The Bataan Death March remains a powerful and painful symbol of the brutality of the Japanese forces during World War II. It is remembered as a significant War Crime and is commemorated annually in the Philippines and the United States to honor the suffering and sacrifice of the prisoners of war. It is a crucial part of remembering the horrors of Philippines History WWII.

Sources:

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. The Fateful Years: Japan’s Adventure in the Philippines, 1941-1945. University of the Philippines Press, 1965. (A foundational Filipino historical account of the period)

- Drea, Edward J. MacArthur’s War: Korea and the Cold War. University Press of Kansas, 2000. (Provides context on MacArthur’s role)

- Morton, Louis. The Fall of the Philippines. U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1953. (The official U.S. Army history, available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://history.army.mil/html/books/05-2/index.html)

- Pacific Wrecks. “Bataan Death March.” https://www.google.com/search?q=https://pacificwrecks.com/events/bataan_death_march.html (Provides detailed information and historical context on the Death March)

- Philippines – World War II. Encyclopædia Britannica. (General overview of the war in the Philippines)

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The Philippines.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. https://www.google.com/search?q=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/philippines (Provides context on the occupation and war crimes)

- Wolff, Leon. Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn. Doubleday, 1960. (Provides pre-war context)

- Report of General MacArthur’s Advanced Echelon to the War Department, 1943-1945. (Primary source documents offering insights into liberation planning)