The history of the Philippines is a saga of resilience, struggle, and the arduous journey from centuries of colonial subjugation to the assertion of its own national destiny. For over 300 years, the archipelago was a distant outpost of the Spanish Empire, and subsequently, after a brief, tumultuous period of revolutionary independence, it became a territory of the United States. The Philippines shift from colony to country was not a singular event but a complex, multi-stage process marked by revolts, intellectual awakening, warfare, political negotiation, and the unwavering aspiration for Philippine independence. This article delves into this pivotal transformation, tracing the historical arc from the late Spanish era through the American period, the Second World War, and ultimately, the formal recognition of Philippine sovereignty on July 4, 1946. Understanding this transition is crucial to grasping the foundations of modern Philippine history, its unique national identity, and the enduring legacies of colonialism and decolonization.

Centuries Under the Spanish Crown: Seeds of Discontent

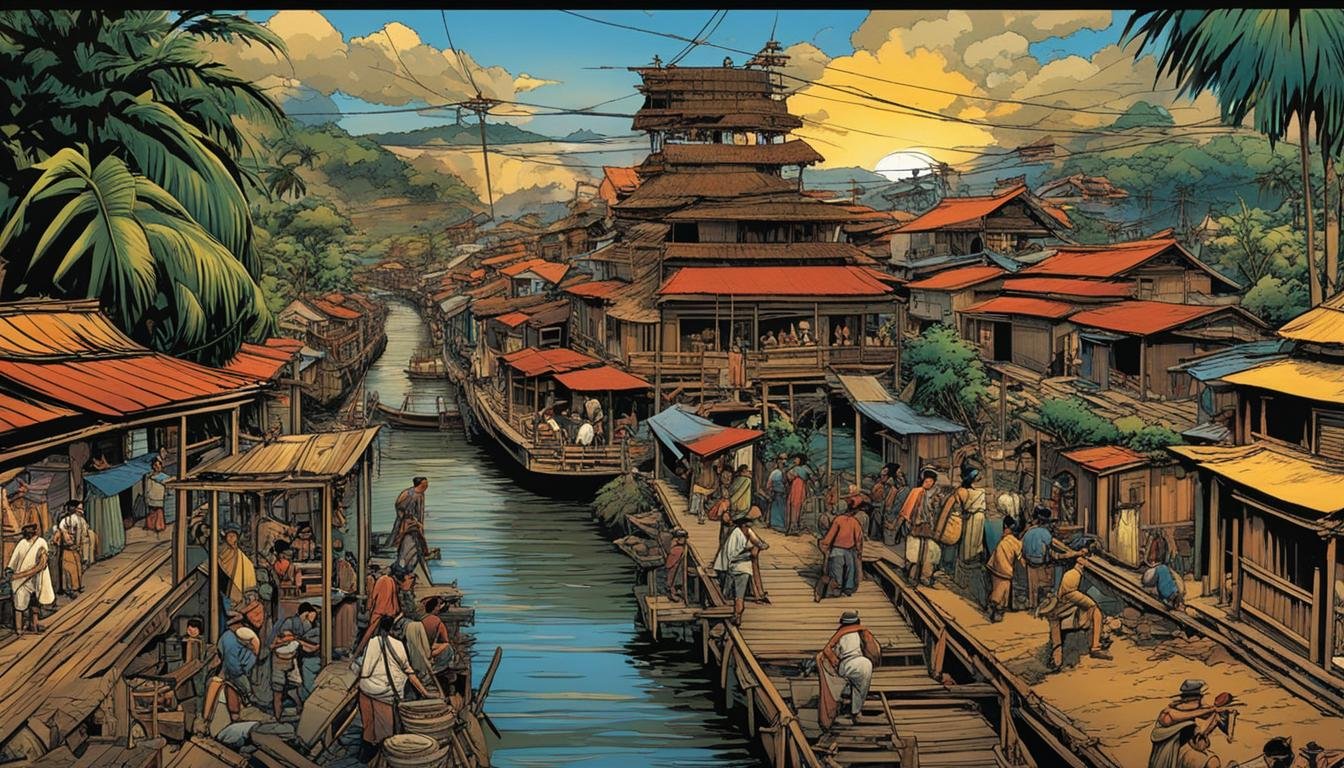

Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines began with the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521 and was formally established by Miguel López de Legazpi in 1565. For over three centuries, Spanish authority profoundly shaped the archipelago’s political, social, cultural, and religious landscape. While Spain introduced Christianity, Western education (albeit limited), and certain administrative structures, its rule was often characterized by exploitation, friarocracy (the political dominance of religious orders), and a rigid social hierarchy that marginalized the native population, known as indios.

Life under Spanish rule varied depending on location and social standing. In urban centers like Manila, a small elite of peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain), insulares (Spaniards born in the Philippines), and wealthy mestizos (of mixed heritage) often held positions of power and privilege. The majority of the population, primarily indigenous Filipinos, lived in rural areas, subject to tribute, forced labor (polo y servicio), and the authority of local officials often influenced by the friars.

The economic policies of the Spanish Crown, such as the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade, benefited Spain and a few elites in the Philippines but did little to develop the local economy comprehensively. Land ownership became increasingly concentrated in the hands of religious orders and Spanish hacienderos, leading to agrarian unrest in various regions.

Despite the imposition of Spanish authority, resistance was a constant feature of the colonial period. Early revolts, often localized and focused on specific grievances like tribute, forced labor, or religious impositions, erupted throughout the archipelago. Figures like Lapu-Lapu, who famously defeated Magellan, symbolize the initial defiance. Later uprisings, such as the Dagohoy Rebellion in Bohol (one of the longest rebellions in Philippine history, lasting over 80 years) or the Silang Revolt in Ilocos led by Diego Silang and his wife Gabriela Silang, demonstrated a persistent desire for autonomy, though they lacked the coordinated national scope required to overthrow Spanish power.

Early Resistance and the Seeds of Nationalism

These early, fragmented resistances, while ultimately suppressed, kept alive a spirit of defiance and laid the groundwork for a broader consciousness. The shared experience of Spanish oppression, despite linguistic and regional differences, began to foster a nascent sense of collective identity among the archipelago’s diverse peoples. Communication improved gradually, and increased interaction, partly due to the colonial administration itself, facilitated the spread of ideas.

The Bourbon Reforms implemented by Spain in the late 18th century, aimed at centralizing administration and increasing revenue, inadvertently stimulated some economic activity and the emergence of a small but growing middle class, including native Filipinos and mestizos who could afford education. This group would become crucial in articulating grievances and formulating demands for reform.

The Age of Enlightenment and the Propaganda Movement

The 19th century saw significant global shifts, including the spread of liberal ideas from Europe and the Americas. These ideas reached the Philippines through increased trade, exposure to foreign literature, and Filipinos who studied abroad. A new generation of educated Filipinos, primarily from the ilustrado class (enlightened ones), emerged as the intellectual vanguard of the growing movement for change.

Recognizing the futility of armed rebellion without broader support and organization, these ilustrados initially advocated for reforms within the Spanish system. This movement, known as the Propaganda Movement, sought to expose the injustices of Spanish rule and demand equal rights for Filipinos, secularization of the clergy, and political representation in the Spanish Cortes.

Key figures of the Propaganda Movement included José Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and Graciano López Jaena. They used their writings, published primarily in La Solidaridad, a newspaper founded in Barcelona in 1889, to criticize the abuses of the friars and colonial officials and to promote a sense of national consciousness. Rizal, through his novels Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not) and El filibusterismo (The Filibustering), vividly depicted the social ills and injustices under Spanish rule, profoundly impacting the developing national identity and fueling nationalist sentiments. While the Propaganda Movement did not achieve its goal of peaceful reform, it successfully awakened a wider segment of the population to the need for change and popularized the concept of “Filipino” as a national identity encompassing all inhabitants of the archipelago, not just Spaniards born locally.

The Katipunan and the Outbreak of Revolution

The failure of the peaceful reform movement convinced many that only armed revolution could achieve genuine change. Inspired by the ideals of the Propaganda Movement but disillusioned with its methods, Andres Bonifacio, a Supremo of humble origins, founded the Kataas-taasan, Kagalang-galangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (Supreme and Most Honorable Society of the Children of the Nation), or Katipunan, on July 7, 1892, the same day Rizal was exiled to Dapitan.

The Katipunan was a secret revolutionary society aimed at achieving full Philippine independence from Spain through armed struggle. It recruited members from various social strata, particularly among the masses, and its revolutionary ideals spread rapidly, particularly in the provinces surrounding Manila. The discovery of the Katipunan by Spanish authorities in August 1896 triggered the Philippine Revolution. Bonifacio and his fellow Katipuneros tore their cedulas (community tax certificates) in the Cry of Pugad Lawin (or Balintawak), signaling their open defiance.

The Philippine Revolution began with a series of uncoordinated uprisings, but it quickly gained momentum, particularly in the province of Cavite. Here, a young general named Emilio Aguinaldo rose to prominence, leading revolutionary forces to significant victories against the Spanish. Internal rivalries, however, soon plagued the revolutionary leadership, leading to the Tejeros Convention in March 1897, where Aguinaldo was elected president of the revolutionary government, a move that led to a tragic rift with Bonifacio, who was later executed.

Despite internal conflicts, the revolution continued, forcing the Spanish government to negotiate. The Pact of Biak-na-Bato in December 1897 led to a temporary truce. Aguinaldo and other revolutionary leaders went into exile in Hong Kong, receiving a sum of money from the Spanish government in exchange for laying down arms. However, this truce was fragile and ultimately failed to address the underlying desire for complete independence.

The Revolution, the First Republic, and the American Intervention

The Spanish-American War, which began in April 1898, dramatically altered the course of the Philippine Revolution. The United States, with its own strategic interests in the Pacific, saw an opportunity to expand its influence. Commodore George Dewey’s decisive victory over the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, effectively ended Spanish naval power in the region and marked the beginning of American military presence in the Philippines.

Seizing the opportunity presented by the American presence and believing the Americans were allies in their struggle against Spain, Emilio Aguinaldo returned from exile and rekindled the revolution. Filipino revolutionaries, with American logistical support, liberated most of the country from Spanish control, surrounding Manila.

Declaration of Independence

On June 12, 1898, taking advantage of the weakening Spanish grip and the presence of American forces, Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed the independence of the Philippines from Spanish rule in Kawit, Cavite. This historic event marked the birth of the First Philippine Republic. The Philippine flag was formally unfurled, and the national anthem, “Lupang Hinirang,” was played for the first time. A constitutional convention was convened in Malolos, Bulacan, which drafted the Malolos Constitution, establishing a republican form of government. This First Republic, though short-lived, was a tangible expression of the Filipino people’s determination to be a sovereign nation.

The Treaty of Paris and Its Aftermath

The aspirations of the newly declared republic were, however, soon dashed by the ambitions of another colonial power. Unbeknownst to the Filipino revolutionaries, Spain and the United States were already negotiating the terms of peace. The Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, between Spain and the United States, formally ended the Spanish-American War. In a move that completely disregarded the declaration of Philippine independence, Spain ceded the Philippines, along with Cuba and Puerto Rico, to the United States for the sum of $20 million.

This treaty was a betrayal of the Filipino people’s hopes and sacrifices. Having fought for and largely achieved independence from Spain, they now found their homeland transferred to a new colonial master without their consent. The stage was set for another, more brutal conflict.

The Philippine-American War

The tension between Filipino forces surrounding Manila and the American troops occupying the city erupted into open conflict on February 4, 1899. This marked the beginning of the Philippine-American War, a brutal and costly struggle for independence against a technologically superior opponent. The war lasted officially until 1902, although sporadic resistance continued for several years thereafter, particularly in the southern Philippines.

The Philippine-American War was characterized by intense conventional battles in its early phase, followed by a shift to guerrilla warfare by the Filipino forces under the leadership of generals like Antonio Luna and Miguel Malvar. The American forces, in turn, employed counter-insurgency tactics, including the establishment of concentration camps, referred to as “reconcentration camps,” and the use of scorched-earth policies in certain areas. The war resulted in significant casualties on both sides, with Filipino civilian deaths estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands due to violence, famine, and disease.

The capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela, in March 1901, dealt a significant blow to the Filipino resistance. Aguinaldo subsequently issued a proclamation calling on his countrymen to lay down their arms and accept American sovereignty. While some continued to fight, organized resistance gradually waned. The end of the war marked the formal establishment of American colonial rule over the Philippines.

The American Colonial Period: A New Master, A Different Approach

The American colonial period (1898-1946) differed significantly from the Spanish era, though it was still fundamentally a period of foreign domination. The United States, influenced by its own historical experience and the prevailing political climate of the time, adopted a policy it termed “Benevolent Assimilation.” This policy, while asserting American sovereignty, also promised to prepare the Philippines for eventual self-governance.

The initial years were focused on pacification and establishing American administrative control. The Spooner Amendment in 1901 marked the transition from military rule to civil government, with William Howard Taft appointed as the first Civil Governor.

Establishing American Control and Institutions

The American colonial government implemented significant changes aimed at modernization and development. Key initiatives included:

- Education: A public education system, accessible to a wider population than under Spain, was established. American teachers, known as Thomasites, arrived in 1901 to teach English, which became the medium of instruction and a unifying language, albeit one that also distanced Filipinos from their indigenous languages. This system produced a new generation of educated Filipinos who would play a crucial role in the independence movement.

- Public Health: Significant strides were made in public health, including the control of infectious diseases like smallpox and cholera, leading to population growth.

- Infrastructure: Investments were made in infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, and ports, primarily to facilitate economic exploitation but also improving connectivity.

- Political Institutions: American models of governance were introduced, including a bicameral legislature. While initially the Philippine Commission, composed of Americans, held legislative power, the Philippine Assembly, an elected body, was established in 1907, providing Filipinos with limited participation in the legislative process.

While these reforms brought tangible improvements in certain areas, they were also designed to consolidate American control and integrate the Philippine economy into that of the United States. The colonial economy became heavily reliant on agricultural exports, particularly sugar, coconut, and abaca, to the American market, making it vulnerable to fluctuations in US demand.

Filipino political leaders, recognizing the need to engage with the American system to achieve independence, participated in the newly established political structures. Figures like Sergio Osmeña and Manuel L. Quezon dominated Philippine politics during this era, advocating for greater autonomy and ultimately, independence.

The Path to Commonwealth

The promise of eventual self-governance, articulated in policies like “Benevolent Assimilation,” fueled the Filipino independence movement. Filipino politicians consistently petitioned the US Congress for greater autonomy and a timeline for independence.

Key legislative milestones in the path to Commonwealth and eventual independence included:

- Philippine Autonomy Act (Jones Law) of 1916: This act replaced the Philippine Commission with a Senate, making both houses of the legislature elected by Filipinos. It also contained a preamble stating the US intention to grant independence to the Philippines as soon as a stable government could be established. This was a significant step, placing the responsibility for demonstrating readiness for self-governance on the Filipinos.

- Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act of 1933: This was the first US law that would have granted the Philippines independence after a 10-year transition period. However, it contained provisions regarding American military bases and trade quotas that were controversial in the Philippines. Manuel L. Quezon, then Senate President, opposed the act, primarily due to the military base provisions, and successfully lobbied for a revised version.

- Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934: This act, largely similar to the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act but with some revisions, was accepted by the Philippine legislature. It provided for the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, a transitional government that would exist for 10 years preceding the granting of full independence on July 4, 1946.

The Commonwealth Era

The Commonwealth of the Philippines was inaugurated on November 15, 1935. Manuel L. Quezon was elected as the first President, with Sergio Osmeña as Vice President. This period was intended to be a crucial phase of preparation for full sovereignty, allowing Filipinos to gain experience in national governance.

The Commonwealth government faced significant challenges, including establishing effective administrative structures, developing the economy, and preparing for national defense. President Quezon initiated various social justice programs and worked towards strengthening the foundations of a future independent state.

However, the carefully planned transition was dramatically interrupted by the outbreak of World War II.

World War II and its Impact on the Shift

World War II had a profound and devastating impact on the Philippines, interrupting the peaceful transition to independence and adding another layer of complexity to the Philippines shift from colony to country.

Japanese Occupation and the Second Republic

Japan launched its invasion of the Philippines shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Despite the joint Filipino-American defense force, Japanese forces quickly gained control. The fall of Bataan in April 1942 and the subsequent infamous Bataan Death March, where thousands of Filipino and American prisoners of war died, became a symbol of the brutal Japanese occupation.

The Japanese established a puppet government, known as the Second Philippine Republic, in 1943, with José P. Laurel as President. While some Filipinos collaborated with the Japanese, many others joined guerrilla movements that continued to resist the occupation throughout the war. This period of Japanese rule was marked by widespread suffering, atrocities, and the disruption of daily life.

The war exposed the vulnerabilities of being a non-sovereign entity and underscored the urgency of achieving genuine independence and the ability to defend one’s nation.

Liberation and the Post-War Landscape

The liberation of the Philippines began with the landing of Allied forces under General Douglas MacArthur in Leyte in October 1944. The campaign to retake the islands was long and arduous, culminating in the Battle of Manila in 1945, which resulted in the near-total destruction of the city and immense civilian casualties.

The end of the war in August 1945 found the Philippines devastated. Infrastructure was destroyed, the economy was in ruins, and the social fabric was strained by years of conflict and occupation. Despite the immense challenges, the commitment to granting the Philippines independence remained.

The Achievement of Full Sovereignty

In accordance with the Tydings-McDuffie Act, the Philippines shift from colony to country culminated on July 4, 1946.

The Formal Transfer of Power

On this historic day, at a ceremony held at Luneta Park in Manila, the United States formally granted independence to the Republic of the Philippines. The American flag was lowered, and the Philippine flag was raised as a symbol of the country’s newfound sovereignty. Manuel Roxas was inaugurated as the first President of the Third Republic of the Philippines (the First Republic being Aguinaldo’s, and the Second being the Japanese-sponsored one).

The choice of July 4th, the American Independence Day, as the date for Philippine independence was symbolic but also somewhat controversial. While it highlighted the role of the United States in granting independence, some felt it overshadowed the Filipino people’s own struggle and sacrifices. In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal declared June 12th, the date of Aguinaldo’s 1898 declaration, as the true Philippine Independence Day, while July 4th was designated as Philippine-American Friendship Day.

Challenges Facing the New Nation

Achieving formal Philippine sovereignty in 1946 did not instantly resolve the myriad challenges facing the new nation. The post-war period was marked by:

- Economic Rehabilitation: Rebuilding the war-devastated economy was a monumental task, requiring significant foreign aid and the development of new economic policies. The Philippine economy remained heavily dependent on trade with the United States due to the Bell Trade Act, which tied the Philippine peso to the US dollar and granted American citizens parity rights in exploiting Philippine natural resources.

- Political Instability: The new government faced internal threats, including the Hukbalahap rebellion, a peasant-based anti-Japanese guerrilla movement that continued its struggle against the post-war government, demanding agrarian reform.

- Establishing National Unity: Forging a cohesive national identity among a diverse population with varying regional loyalties and experiences of colonialism was an ongoing process.

The transition from being a colony to a fully functioning country required not just political independence but also the building of robust institutions, a stable economy, and a strong sense of shared nationhood.

Forging a National Identity and Navigating Post-Colonial Challenges

The formal declaration of independence in 1946 was a critical milestone, but the process of fully realizing Philippine sovereignty and forging a distinct national identity continued long after. The legacies of Spanish and American colonial rule deeply influenced Philippine society, politics, culture, and economy.

Defining Filipino Identity

Centuries of foreign rule resulted in a complex and multifaceted national identity. While Spanish colonialism left an indelible mark on religion (Catholicism), language (Spanish loanwords in Filipino languages), and social customs, American rule introduced democratic institutions, the English language, and popular culture that continue to influence the Philippines today.

The struggle for independence itself became a powerful unifying narrative, celebrating national heroes like José Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, and Emilio Aguinaldo. The concept of bayanihan (community spirit) and resilience in the face of adversity became central to the Filipino self-image.

Defining what it meant to be Filipino involved navigating the influences of both Eastern and Western cultures, indigenous traditions, and the shared historical experience of struggle. This process continues to evolve, shaped by contemporary challenges and global interactions.

Political and Economic Development in the Republic

The early decades of the Republic were marked by efforts to consolidate democratic institutions, implement economic development plans, and address social inequalities. However, the path was not smooth. Political corruption, economic dependency, and social unrest posed significant challenges.

The period saw a succession of presidents grappling with these issues. The declaration of Martial Law by President Ferdinand Marcos in 1972, citing the need to suppress insurgency and establish a “New Society,” marked a departure from democratic norms and led to a period of authoritarian rule. While Marcos’s regime initiated significant infrastructure projects, it was also characterized by human rights abuses, corruption, and the suppression of dissent.

The peaceful People Power Revolution in 1986, which overthrew the Marcos regime and restored democracy, was another pivotal moment in the ongoing development of Philippine sovereignty and the assertion of the people’s will. It demonstrated the continued vitality of democratic aspirations forged during the colonial and independence struggles.

Legacies of Colonialism and the Ongoing Journey of Nationhood

The Philippines shift from colony to country left behind complex legacies. The democratic institutions introduced by the Americans, though imperfect, provided a framework for self-governance. The education system produced an educated citizenry capable of participating in national life. However, colonialism also contributed to persistent issues such as social inequality, regional disparities, and a political culture sometimes influenced by patronage and personalistic politics.

The journey of nationhood is an ongoing process. The Philippines continues to grapple with challenges related to poverty, governance, external relations, and asserting its place in the global community. Understanding the historical arc from colony to country provides essential context for appreciating the complexities of the present-day Philippines and the enduring spirit of a nation that fought hard to gain its place among the sovereign states of the world. The lessons learned from the struggle for independence, the challenges of the Commonwealth era, the disruption of World War II, and the early decades of the Republic continue to shape the country’s aspirations and its path forward.

Key Takeaways:

- The Philippines shift from colony to country was a long and arduous process, not a single event.

- Spanish colonial rule (over 300 years) created the conditions for discontent and the rise of nationalism.

- The Propaganda Movement intellectually prepared the ground for revolution, led by figures like José Rizal.

- The Katipunan, founded by Andres Bonifacio, launched the armed Philippine Revolution.

- The declaration of independence in 1898 and the First Republic were short-lived due to American intervention following the Spanish-American War and the Treaty of Paris.

- The Philippine-American War was a brutal conflict resulting from the US annexation of the Philippines.

- The American colonial period introduced significant reforms (education, infrastructure) but maintained foreign control, while also setting the path to Commonwealth and eventual independence through acts like the Tydings-McDuffie Act.

- The Commonwealth of the Philippines under leaders like Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña was a crucial preparatory phase, interrupted by World War II.

- Full Philippine sovereignty was achieved on July 4, 1946, marking the formal end of the colonial era.

- The new nation faced immediate challenges in economic rehabilitation, political stability, and forging a unified national identity, legacies that continue to shape the country today.

- The journey from colony to country highlights the resilience of the Filipino people and their unwavering desire for self-determination.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

- When did the Philippines gain independence? The Philippines officially gained independence from the United States on July 4, 1946, in accordance with the Tydings-McDuffie Act. However, many Filipinos consider June 12, 1898 (declaration of independence from Spain) as the true Independence Day.

- Who were the key figures in the Philippine independence movement? Major figures include José Rizal (intellectual leader of the Propaganda Movement), Andres Bonifacio (founder of the Katipunan and leader of the early Philippine Revolution), Emilio Aguinaldo (leader of the later stages of the Revolution, first President of the First Republic), Manuel L. Quezon (first President of the Commonwealth), and Sergio Osmeña (Vice President of the Commonwealth and later President). Many others played crucial roles at local and national levels.

- What was the significance of the Treaty of Paris (1898) for the Philippines? The Treaty of Paris ended the Spanish-American War and resulted in Spain ceding the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. This was a pivotal moment as it transferred the Philippines from one colonial power to another without the consent of the Filipino people, directly leading to the Philippine-American War.

- What was the Tydings-McDuffie Act? The Tydings-McDuffie Act, passed by the US Congress in 1934, provided for the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines as a 10-year transition period leading to full Philippine independence on July 4, 1946.

- How did World War II impact the shift from colony to country? World War II interrupted the Commonwealth period and the planned transition to independence. The brutal Japanese occupation and the subsequent liberation campaign devastated the country but also underscored the urgent need for genuine sovereignty and the ability to defend the nation.

- What were the immediate challenges the Philippines faced after gaining independence in 1946? The new Republic faced immense challenges including rebuilding a war-devastated economy, addressing political instability (like the Hukbalahap rebellion), establishing effective governance, and forging a unified national identity amidst the legacies of centuries of colonialism.

- Is the Philippines still affected by its colonial past? Yes, the legacies of both Spanish colonial rule and the American colonial period continue to influence various aspects of Philippine society today, including its political system, legal framework, educational system, culture, and economic structure. The ongoing process of defining national identity and achieving full Philippine sovereignty in practice is a continuous negotiation with this historical inheritance.

Sources:

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1990). History of the Filipino People. Garotech Publishing. (A widely cited comprehensive history of the Philippines)

- Constantino, Renato. (1975). The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Tala Publishing Services. (A nationalist perspective on Philippine history)

- Stanley, Peter W. (1974). A Nation in the Making: The Philippines and the United States, 1899-1921. Harvard University Press. (Focuses on the early American colonial period)

- Zaide, Gregorio F. & Sonia M. Zaide. (1999). Philippine History and Government. All-Nations Publishing Co. (A commonly used textbook)

- National Historical Commission of the Philippines. (Various publications and online resources). http://nhcp.gov.ph/ (Official government source for historical information)

- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Treaty of Peace Between the United States and Spain; December 10, 1898. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/sp1898.asp (Primary source for the Treaty of Paris)

- United States. Congress. (1934). Tydings-McDuffie Act. (Public Law 73-127). (Primary source for the independence act)

(Note: Specific page numbers or editions are not provided for brevity, but these are reputable sources for further research on Philippine History).