A Nation Reborn, A Population Transformed

The period following World War II marked a profound turning point in Philippine history. Emerging from the devastation of war and achieving full independence from the United States on July 4, 1946, the newly established Third Philippine Republic faced the monumental task of reconstruction and nation-building. Central to this era was the dramatic transformation of the Philippine Population. The years between 1946 and 1972, preceding the declaration of Martial Law, witnessed significant shifts in Demographic Trends, characterized by unprecedented growth, changing settlement patterns, and evolving social structures. Understanding these population dynamics is crucial for comprehending the social, economic, and political landscape of the Philippines during this formative Post-War Era (1946-1972).

This article delves into the complex interplay of factors that shaped the Philippine population during these critical decades. We will explore the post-war recovery’s impact on population size, the drivers behind the remarkable Population Growth Rate, including the notable Baby Boom and declining Mortality Rates. Furthermore, we will examine the surge in Urbanization and Internal Migration, focusing on the growth of key cities like Manila and Cebu, and the push-and-pull factors driving these movements, including agrarian issues and conflict. The influence of Public Health improvements, advancements in Education, the challenges of Economic Development, and the nascent discussions around Family Planning will also be analyzed. Finally, we will consider these trends within the broader context of the Third Philippine Republic, including political stability challenges like the Hukbalahap Rebellion, the complexities of Agrarian Reform, and the overarching influence of the global Cold War Context.

Setting the Stage: The Philippines After World War II (1946)

The Philippines emerged from World War II physically devastated and psychologically scarred. Major cities, particularly Manila, lay in ruins, second only to Warsaw in terms of wartime destruction. Infrastructure – roads, bridges, power systems, communication lines – was severely damaged. The agricultural sector, the backbone of the economy, was disrupted, leading to food shortages in the immediate aftermath.

The human cost was immense. Estimates suggest over a million Filipinos perished during the war due to direct conflict, massacres, disease, and starvation. This significant loss temporarily impacted the population structure, but the end of hostilities and the dawn of independence set the stage for a dramatic demographic rebound.

Initial Demographic Realities:

- Population Estimates: Precise figures immediately post-war were challenging to ascertain due to disrupted census mechanisms. However, the 1939 census recorded a population of around 16 million. By the first post-war census in 1948, the population had surged to over 19.2 million, indicating rapid recovery and growth despite wartime losses.

- Reconstruction Challenges: The immediate focus was on rebuilding homes, infrastructure, and the economy. This reconstruction effort itself influenced population movements, as people returned to rebuilt areas or sought opportunities in burgeoning recovery zones.

- Political Transition: The establishment of the Third Philippine Republic brought hopes of stability and progress, creating a socio-political environment conducive to family formation and growth, despite underlying political tensions and the simmering Hukbalahap Rebellion in Central Luzon.

This context of recovery, reconstruction, and newfound independence formed the backdrop against which the significant Demographic Trends of the Post-War Era (1946-1972) unfolded.

The Post-War Baby Boom Phenomenon

One of the most defining demographic features of this era was a significant surge in birth rates, often referred to as the Philippine Baby Boom. While perhaps less sharply defined than its Western counterpart, the trend was undeniable and contributed significantly to the escalating Population Growth Rate.

Drivers of the Boom:

- Return to Normalcy: The end of the war and Japanese occupation brought a sense of relief and optimism. Couples reunited, marriages postponed during the conflict took place, and families felt more secure about bringing children into the world.

- Improved Peace and Order (Relatively): While regional insurgencies like the Hukbalahap Rebellion persisted, the general cessation of large-scale warfare across the archipelago created a more stable environment compared to the war years.

- Cultural Factors: Traditional Filipino values emphasizing large families remained strong. Children were often seen as economic assets, particularly in rural agricultural settings, and symbols of family continuity.

- Declining Infant and Child Mortality: As discussed later, improvements in Public Health meant more children survived infancy and childhood, contributing to larger effective family sizes even if fertility rates remained constant initially.

Impact on Population Growth:

The combination of high birth rates and falling death rates resulted in an accelerating Population Growth Rate.

| Census Year | Population (Approx.) | Average Annual Growth Rate (Intercensal) |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 19.2 Million | – |

| 1960 | 27.1 Million | ~3.06% |

| 1970 | 36.7 Million | ~3.01% |

| (1975) | (42.1 Million) | ~(2.78%) |

Export to Sheets

Note: Growth rates are approximate averages between census years. The 1975 data is included for trend context beyond the primary period.

This rapid growth, averaging around 3% annually for much of the period, meant the Philippine Population nearly doubled between 1948 and 1970. This demographic explosion would have profound implications for resource allocation, Economic Development, social services, and the environment in the decades to follow.

Trends in Mortality Rates and Public Health

Concurrent with the high birth rate was a significant decline in Mortality Rates, another crucial factor driving the rapid Population Growth Rate. The Post-War Era (1946-1972) saw concerted efforts, often supported by international aid (partially influenced by the Cold War Context emphasis on development), to improve Public Health.

Key Developments:

- Disease Control: Major campaigns targeted infectious diseases that were primary causes of death. DDT spraying significantly reduced malaria prevalence, although environmental concerns emerged later. Vaccination programs against smallpox, cholera, and tuberculosis (BCG) became more widespread. The availability of antibiotics like penicillin dramatically reduced deaths from bacterial infections.

- Sanitation and Water: Efforts were made to improve access to potable water and basic sanitation, particularly in urbanizing areas, though progress was uneven and often lagged behind population growth. Government agencies and international organizations played roles in these infrastructure projects.

- Expansion of Health Services: While still concentrated in urban centers and facing resource constraints, the number of hospitals, rural health units (RHUs), and trained medical personnel (doctors, nurses, midwives) gradually increased throughout the period. The establishment of the Department of Health as a key government ministry signaled a commitment to public welfare.

- Maternal and Child Health: Focus on improving prenatal care, skilled birth attendance (though traditional hilots remained prevalent), and nutritional programs aimed to reduce maternal and infant mortality.

Impact:

- Increased Life Expectancy: Average life expectancy at birth, while still low by modern standards, saw steady improvement throughout this period, rising from estimated figures in the 40s post-war to the high 50s or low 60s by the early 1970s.

- Reduced Infant and Child Mortality: While still high compared to developed nations, the rates of death among infants and young children saw marked declines, meaning more individuals survived to reproductive age, further fueling population growth.

These Public Health successes, however, were tempered by persistent challenges: stark rural-urban disparities in access to care, limited funding, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and the emergence of health problems associated with rapid Urbanization.

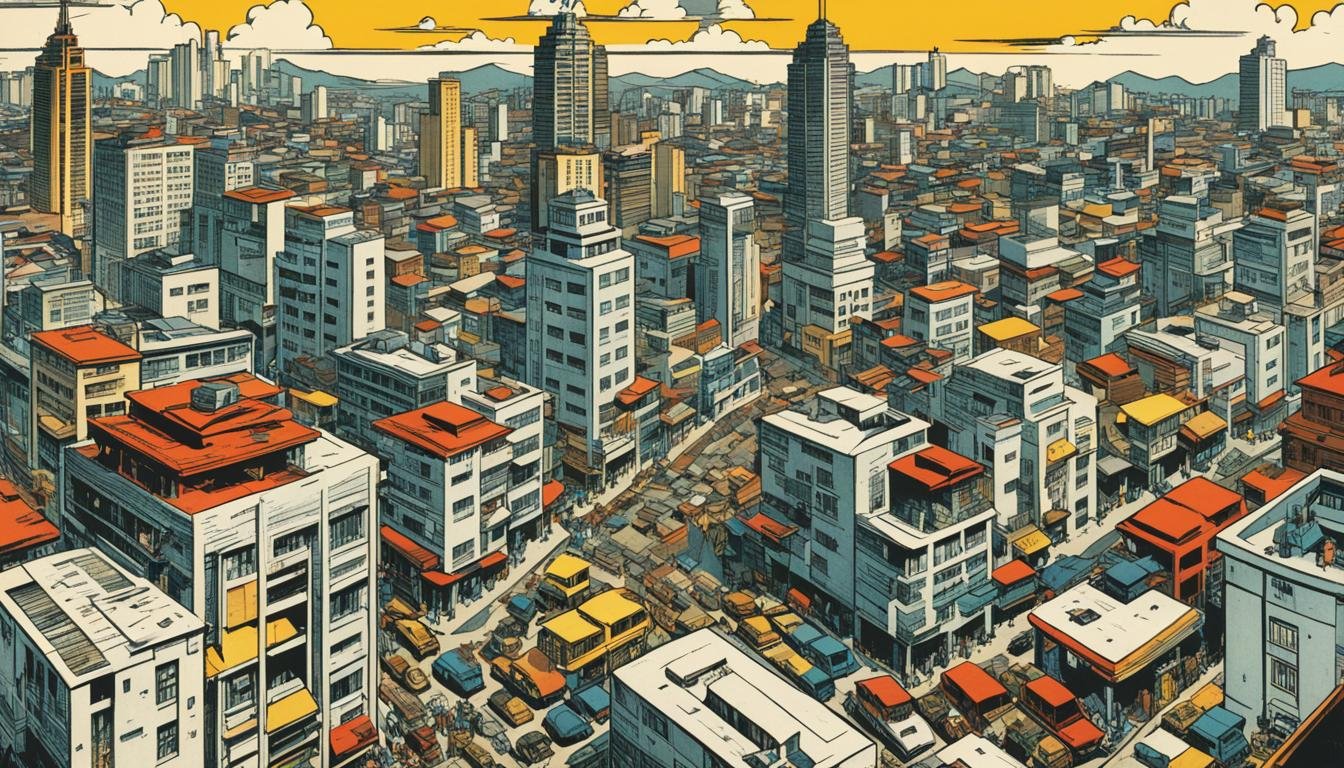

Urbanization and Internal Migration Patterns

The decades from 1946 to 1972 witnessed a dramatic acceleration of Urbanization and large-scale Internal Migration. Filipinos moved from rural areas to cities in unprecedented numbers, fundamentally reshaping the country’s settlement patterns.

Drivers of Migration:

- Push Factors (Rural):

- Rural Poverty: Limited economic opportunities, lack of non-farm jobs, and persistent poverty in agricultural communities drove many to seek fortunes elsewhere.

- Agrarian Issues: Unequal land distribution, tenure insecurity, and the slow pace of effective Agrarian Reform frustrated many tenant farmers and landless workers. While reforms were attempted under various presidents of the Third Philippine Republic, their impact was often limited, failing to stem the tide of out-migration.

- Conflict and Instability: The ongoing Hukbalahap Rebellion in Central Luzon (peaking in the late 1940s and early 1950s) displaced many families and made rural life precarious in affected areas. Other localized conflicts also contributed to population movements.

- Limited Rural Services: Poorer access to Education, healthcare, and basic amenities in many rural areas compared to urban centers.

- Pull Factors (Urban):

- Perceived Economic Opportunities: Cities, especially Metro Manila, were seen as centers of employment, industry, trade, and government, offering the promise (though not always the reality) of better wages and jobs.

- Educational Opportunities: Major universities and colleges were concentrated in urban areas, attracting students who often stayed on after graduation. Access to higher Education was a significant pull factor.

- Modern Amenities: Cities offered access to electricity, entertainment, better infrastructure, and a wider range of goods and services, representing a ‘modern’ lifestyle attractive to many.

Growth of Urban Centers:

- Metro Manila: As the national capital and primary economic hub, Manila experienced explosive growth. Its population swelled, leading to the expansion of the metropolitan area and the proliferation of informal settlements (slums) as infrastructure struggled to keep pace.

- Cebu City: As the major urban center in the Visayas, Cebu also saw significant population growth, driven by trade, commerce, and its role as a regional hub.

- Other Cities: Davao City in Mindanao, Iloilo City in Western Visayas, and other regional centers also experienced substantial growth due to migration.

Challenges of Rapid Urbanization:

This rapid, often unplanned, Urbanization brought significant challenges:

- Severe housing shortages and the rise of slum communities.

- Overburdened infrastructure (transport, water, sanitation, power).

- Increased pressure on social services.

- Traffic congestion and pollution (particularly in Manila).

- Rising urban poverty and unemployment/underemployment.

The dynamic of Internal Migration and Urbanization became a defining characteristic of Philippine Population distribution during the Post-War Era (1946-1972).

Socio-Economic Development and Population Dynamics

The relationship between Demographic Trends and Economic Development during this period was complex and bidirectional. The rapid Population Growth Rate presented both opportunities (a larger domestic market, abundant labor) and significant challenges for economic planners.

- Economic Context: The Philippine economy during the Third Philippine Republic experienced periods of growth, often fueled by reconstruction aid, agricultural exports, and early industrialization efforts (import substitution). However, growth was often hampered by political instability, corruption, reliance on primary exports, and unequal distribution of wealth.

- Population Growth vs. Economic Growth: A key debate emerged: Was rapid population growth hindering Economic Development? Many economists and policymakers argued that the high Population Growth Rate diluted the gains from economic growth, meaning GDP per capita grew much slower than overall GDP. More people meant greater demand for food, housing, jobs, Education, and health services, straining government budgets and resources.

- Labor Force: The growing population resulted in a rapidly expanding labor force. However, job creation often failed to keep pace, leading to persistent unemployment and underemployment, particularly in urban areas swelled by Internal Migration.

- Resource Pressure: A larger population increased pressure on natural resources, particularly land for agriculture and settlement, forests, and fisheries. This laid the groundwork for future environmental challenges.

- Dependency Ratio: The Baby Boom initially led to a high dependency ratio (a large proportion of young, non-working individuals relative to the working-age population), putting pressure on families and the state to provide for children’s needs.

While the government pursued various Economic Development plans, explicitly incorporating population variables into planning remained limited until the latter part of this era, when concerns about the rapid growth rate became more prominent.

The Role of Education in Demographic Shifts

The Post-War Era (1946-1972) saw a significant expansion of the Philippine Education system, driven by a strong societal value placed on schooling and government efforts to increase access. This expansion had subtle but important links to Demographic Trends.

- Increased Literacy and Enrollment: Literacy rates improved, and enrollment in primary, secondary, and tertiary education grew substantially. The Philippines achieved relatively high literacy and enrollment rates compared to other Southeast Asian nations at the time.

- Education as a Migration Driver: As mentioned earlier, the concentration of higher education institutions in cities like Manila and Cebu was a major pull factor for Internal Migration.

- Education and Fertility (Emerging Trends): While the full impact would be felt later, increased educational attainment, particularly for women, began to correlate subtly with changing attitudes towards family size and potentially delayed marriage or childbirth. Educated individuals often sought non-agricultural employment where large families were less of an economic necessity. However, cultural norms supporting high fertility remained dominant throughout most of this period.

- Informed Populace: A more educated populace became increasingly aware of national issues, including those related to population growth, Economic Development, and social services, potentially influencing public discourse and later policy debates on Family Planning.

The expansion of Education was thus intertwined with Urbanization, migration, and the gradual evolution of social norms that would eventually influence fertility trends more significantly in subsequent decades.

Emerging Discourse on Family Planning (Late 1960s – Early 1970s)

While high fertility rates characterized most of the Post-War Era (1946-1972), the late 1960s saw the beginnings of a national discourse on population control and Family Planning.

- Growing Awareness: Planners, academics, and some policymakers began to publicly articulate concerns that the rapid Population Growth Rate was hindering Economic Development and straining public resources (Public Health, Education, infrastructure).

- International Influence: International organizations (like the UN, USAID, World Bank, Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation) became increasingly active globally in promoting population control as part of development assistance, heavily influenced by the Cold War Context where stabilizing populations in developing nations was seen as strategically important. These organizations provided funding and technical assistance for Family Planning initiatives in the Philippines.

- Formation of NGOs: Private organizations, often funded internationally, began promoting family planning methods and services. The Family Planning Organization of the Philippines (FPOP) was established in 1969.

- Government Response: In 1967, President Ferdinand Marcos signed the UN declaration on population. In 1969, he created the Commission on Population (POPCOM) tasked with formulating national population policy. While official policy promoting Family Planning was still nascent and faced opposition (notably from the Catholic Church), its emergence marked a significant shift from the largely pro-natalist stance of the earlier post-war years. The groundwork was laid for more extensive programs that would be implemented under Martial Law.

This emerging focus signaled a recognition at the highest levels that the Demographic Trends observed over the preceding decades, particularly the high Population Growth Rate, required policy attention.

Regional Variations in Demographic Trends

While national trends provide an overall picture, Demographic Trends were not uniform across the Philippine archipelago during the Post-War Era (1946-1972).

- Luzon: Experienced the most intense Urbanization, particularly around the national capital region of Manila. Central Luzon, despite being affected by the Hukbalahap Rebellion, remained a key agricultural area and source of migrants. Northern Luzon saw relatively slower growth compared to the central and southern parts.

- Visayas: Islands like Cebu, Panay (Iloilo), and Negros saw significant urban growth in their main cities but also experienced substantial out-migration from poorer rural areas, often towards Manila or frontier areas in Mindanao. Traditional agricultural economies faced challenges, contributing to migration pressures.

- Mindanao: Often viewed as a “land of promise,” Mindanao attracted significant Internal Migration from Luzon and the Visayas, fueled by government resettlement programs (partly aimed at easing Agrarian Reform pressures elsewhere) and perceptions of land availability. This led to rapid population growth in many parts of Mindanao but also contributed to ethnic tensions over land resources in later years.

Understanding these regional differences is essential for a nuanced view of Philippine Population dynamics, highlighting the varying impacts of Economic Development, conflict, Agrarian Reform policies, and resource availability across the country.

Conclusion: Shaping Modern Demographics

The Post-War Era (1946-1972) was a period of profound demographic transformation for the Philippines. Independence and recovery unleashed forces that led to a dramatic increase in the Philippine Population, driven by a combination of high birth rates (the Baby Boom) and declining Mortality Rates due to improvements in Public Health. This era firmly established a high Population Growth Rate that would shape the nation’s trajectory for decades.

Simultaneously, vast Internal Migration flows reshaped settlement patterns, accelerating Urbanization and fueling the growth of cities like Manila and Cebu, while also populating frontier regions like Mindanao. These movements were driven by complex push factors like rural poverty and limited Agrarian Reform, and pull factors like the lure of urban opportunities and Education.

These Demographic Trends unfolded within the specific historical context of the Third Philippine Republic, interacting constantly with efforts at Economic Development, political challenges like the Hukbalahap Rebellion, the expansion of Education, and the global Cold War Context. By the end of this period, the sheer scale of population growth led to emerging concerns and the initial stages of Family Planning promotion, setting the stage for different demographic policies under the subsequent Martial Law regime. The demographic foundations laid between 1946 and 1972 fundamentally influenced the social, economic, and political landscape of the modern Philippines.

Key Takeaways:

- The Post-War Era (1946-1972) saw the Philippine Population nearly double due to high birth rates (Baby Boom) and falling Mortality Rates.

- Improvements in Public Health (disease control, sanitation) significantly lowered death rates and increased life expectancy.

- Massive Internal Migration occurred from rural areas to cities, driving rapid Urbanization, especially in Manila and Cebu.

- Rural poverty, Agrarian Reform issues, and conflict (Hukbalahap Rebellion) pushed people out, while urban jobs and Education pulled them in.

- Rapid Population Growth Rate presented challenges for Economic Development, resource management, and provision of social services during the Third Philippine Republic.

- Concerns about population growth led to the emergence of Family Planning discourse and initiatives in the late 1960s, influenced partly by the Cold War Context.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

- Q1: What were the main reasons for the rapid population growth in the Philippines after WWII (1946-1972)?

- The primary drivers were a persistently high birth rate (post-war Baby Boom, cultural norms favoring large families) combined with a significant decline in Mortality Rates due to improved Public Health measures (disease control, sanitation, basic healthcare access). More children were being born, and more people were surviving longer.

- Q2: How did urbanization change the Philippines during this period?

- Urbanization concentrated population and economic activity in cities like Manila and Cebu. This led to economic dynamism but also created major challenges like housing shortages, infrastructure strain, traffic, pollution, and the growth of informal settlements (slums), profoundly altering the physical and social landscape.

- Q3: Was the Hukbalahap Rebellion a significant factor in demographic trends?

- Yes, particularly in Central Luzon during the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Hukbalahap Rebellion caused displacement, disrupted rural life, and acted as a localized ‘push’ factor contributing to Internal Migration away from conflict zones towards safer areas or urban centers. Its roots were also tied to unresolved Agrarian Reform issues, which were broader drivers of migration.

- Q4: Did the government try to manage population growth during the Third Philippine Republic (1946-1972)?

- For most of this period, there was no active government policy to limit population growth. The focus was primarily on Economic Development and reconstruction. However, by the late 1960s, growing awareness of the challenges posed by the rapid Population Growth Rate, coupled with international influence (Cold War Context), led to the creation of the Commission on Population (POPCOM) in 1969 and the beginnings of official discourse and programs related to Family Planning.

- Q5: How did the demographic trends of 1946-1972 impact later Philippine history?

- These trends created a large, young population structure that continued to drive growth for decades. The rapid Urbanization patterns established persistent challenges for city management and development. The sheer size of the Philippine Population became a central factor in economic planning, environmental concerns, and political discourse, including the more assertive population policies implemented during the Martial Law era (post-1972). The socio-economic pressures related to population density and resource competition remain relevant today.

Sources:

- Abinales, P. N., & Amoroso, D. J. (2017). State and Society in the Philippines. Rowman & Littlefield. (Provides broad historical context for the Third Republic).

- Caoili, Manuel A. (1988). The Origins of Metropolitan Manila: A Political and Social Analysis. New Day Publishers. (Focuses on the growth and challenges of Manila’s urbanization).

- Concepcion, Mercedes B. (Ed.). (1977). Population of the Philippines. CICRED Series. (Although slightly later, often references data and trends from the period).

- Doeppers, Daniel F. (1984). Manila, 1900-1941: Social Change in a Late Colonial Metropolis. Yale University Press. (Provides pre-war context for Manila’s demographic patterns).

- Guerrero, Milagros C. (1998). A Survey of Philippine History. (Standard textbook offering chronological overview).

- Kerkvliet, Benedict J. Tria. (1977). The Huk Rebellion: A Study of Peasant Revolt in the Philippines. University of California Press. (Details the Hukbalahap movement and its socio-economic context, relevant to migration).

- National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) & National Statistics Office (NSO – now Philippine Statistics Authority, PSA). Philippine Census Reports (1948, 1960, 1970). (Primary data sources for population figures).

- Owen, Norman G. (Ed.). (1999). The Philippine Economy and the United States: Studies in Past and Present Interactions. University of Michigan Press. (Discusses economic factors influencing the period).

- Pertierra, Raul. (Various works on Philippine social change and migration).

- Zaide, Gregorio F., & Zaide, Sonia M. (1990). Philippine History and Government. National Book Store. (General textbook covering the period).