The history of the Spanish colonial Philippines is a complex tapestry woven from the threads of various peoples, cultures, and power structures. At the very apex of this intricate social and political pyramid stood the Peninsulares. These were individuals born in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain) who journeyed across vast oceans to administer, exploit, and govern the distant territories of the Spanish Crown, including the Philippine archipelago. Their presence and dominance profoundly shaped the course of Philippine history for over three centuries. Understanding the life of the Filipino Peninsulares is not merely about chronicling the experiences of a select few; it is crucial for comprehending the dynamics of Spanish rule, the development of a rigid racial stratification and social hierarchy, and the deep-seated tensions that would eventually contribute to the clamor for reform and, ultimately, revolution.

Unlike the Insulares (or Criollos), Spaniards born in the colonies, the Peninsulares held a distinct and almost unassailable advantage in the colonial system. Their birthplace was their key to privilege, guaranteeing them preferential access to the highest positions in government, military, and the church. This article delves into the multifaceted existence of these powerful individuals, exploring their arrival, their roles within the colonial administration, their economic activities, their social standing, their interactions with other segments of society, and the factors that led to the erosion of their seemingly absolute authority in the waning years of Spanish colonial Philippines. We will examine their daily lives within the walled city of Intramuros, their connection to the lucrative Galleon Trade, and their often contentious relationship with the Insulares and the native Indio population, as well as the rising class of Mestizos and principalia.

Arrival and Establishing Dominance

The initial waves of Spaniards arriving in the Philippines following Ferdinand Magellan’s arrival in 1521 and Miguel López de Legazpi’s colonization efforts starting in 1565 were, by definition, Peninsulares. They were soldiers, administrators, and missionaries tasked with claiming and consolidating the new territory for Spain. Legazpi himself, the first Governor-General of the Philippines, was a Peninsular. These early arrivals laid the groundwork for the colonial structure, establishing the city of Manila as the capital in 1571 and instituting key institutions of Spanish rule.

The motivations for their arduous journey were varied but often centered on opportunity: to serve the Crown, to spread Christianity, to seek fortune, or to gain prestige unavailable to them in Spain. Unlike later periods where a more defined administrative structure existed, the initial phase was characterized by conquest and the establishment of basic governance and tribute systems. These early Peninsulares faced immense challenges, including resistance from local populations, conflicts with rival European powers (such as the Dutch and Portuguese), and the logistical difficulties of managing a distant colony. Yet, their success in establishing a foothold cemented the Philippines’ place within the vast Spanish Empire and paved the way for the continuous arrival of more Peninsulares seeking power and wealth.

The Pinnacle of the Social Hierarchy

Within the rigid social hierarchy of the Spanish colonial system, the Peninsulares occupied the indisputable top rung. This was a system built on birthright and proximity to the imperial center. The hierarchy was broadly structured as follows:

- Peninsulares: Spaniards born in Spain. Held the highest positions.

- Insulares (Criollos): Spaniards born in the Philippines. Generally ranked below Peninsulares, leading to significant resentment.

- Mestizos: Individuals of mixed race (Spanish and native, or Spanish and Chinese, etc.). Their status varied depending on their specific lineage and wealth.

- Principalia: The native elite who collaborated with Spanish authorities. Held local power but were subordinate to the Spanish.

- Indios: Native inhabitants of the Philippines. Occupied the lowest rung of the social ladder, subject to tribute and forced labor.

This system of racial stratification was not merely social; it had direct implications for political power and economic opportunity. A Peninsular, regardless of their actual capabilities, was almost always preferred over an Insular for key positions. This systematic discrimination against the Insulares, who increasingly identified with the Philippines as their homeland, was a major source of friction throughout the colonial period.

Political and Administrative Power

The political landscape of the Spanish colonial Philippines was dominated by the Peninsulares. The most powerful figure was the Governor-General, appointed directly by the King of Spain, often after consultation with the Consejo de Indias (Council of the Indies) in Madrid. The Governor-General held immense power, acting as the King’s representative, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and head of the colonial administration and judiciary (as President of the Real Audiencia). This position was exclusively reserved for Peninsulares.

Other crucial positions exclusively or predominantly held by Peninsulares included:

- Members of the Real Audiencia: The highest judicial body in the colony, also serving as an advisory council to the Governor-General and sometimes acting as interim governor.

- Alcaldes Mayores: Provincial governors responsible for administering justice, collecting tribute, and promoting economic activities in their respective provinces.

- Oidores: Judges of the Real Audiencia.

- High-ranking military officers: Commanders of regiments and fortifications.

- High-ranking church officials: Archbishops, bishops, and heads of religious orders.

The constant influx of Peninsulares into these positions, often for relatively short terms (to prevent them from building too much personal power or influence), meant that the top layers of governance were perpetually staffed by individuals with limited long-term investment or understanding of the local context, beyond their administrative duties. This system reinforced control from Spain but also created inefficiency and fostered resentment among those born in the colony. The administration was centralized in Manila, specifically within Intramuros, the walled city that served as the seat of Spanish power.

Economic Influence and the Galleon Trade

Economic control was another pillar of Peninsular dominance. The Galleon Trade, which connected Manila with Acapulco in Mexico from 1565 to 1815, was the economic lifeline of the colony and a primary source of wealth for the Peninsulares. This trade involved exchanging silks, porcelain, spices, and other goods from Asia (primarily China) for silver from the Americas.

While the Galleon Trade was technically a royal monopoly managed through the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) in Seville (and later Cadiz), the actual participation and benefit in Manila were heavily skewed towards the Peninsulares. They controlled the limited number of boletas (tickets or licenses) required to ship goods on the galleons. These boletas were highly valuable and often traded hands for significant sums, becoming a source of speculation and wealth accumulation for the elite.

Beyond the Galleon Trade, Peninsulares also controlled other significant economic activities:

- Land Ownership: Though not as extensive as in some other Spanish colonies (due to the importance of the communal land system and religious orders as major landowners), Peninsulares could acquire large estates (haciendas), often through royal grants or by consolidating smaller landholdings.

- Monopolies: They held monopolies on certain goods like tobacco, which became a major state-controlled enterprise in the 18th century.

- Control of Local Trade: Through their positions as Alcaldes Mayores, Peninsulares often engaged in indulto de comercio, a legal but often abused privilege that allowed them to engage in trade within their provinces, often at the expense of local merchants.

This economic power reinforced their political dominance, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of privilege. The wealth generated from these activities allowed Peninsulares to live lives of luxury, further distinguishing them from the rest of colonial society.

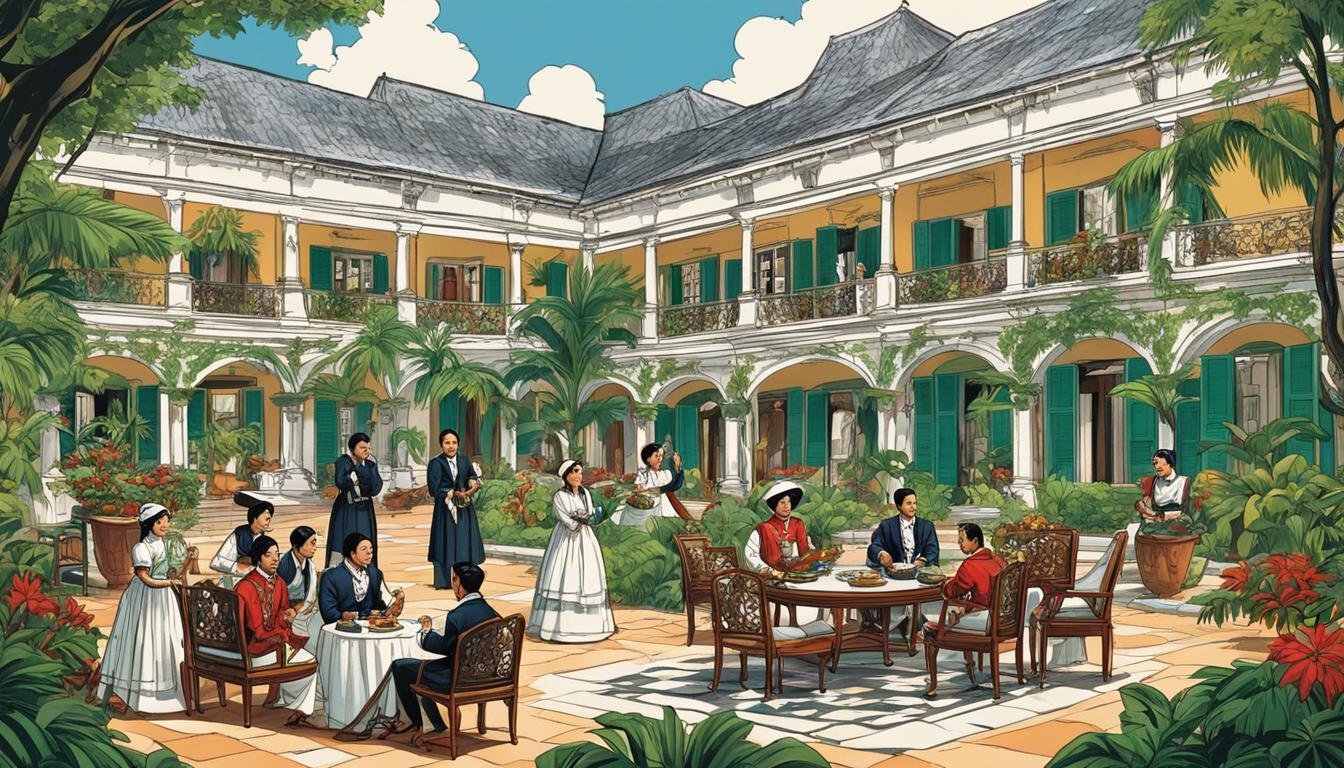

Daily Life and Social Circles in Intramuros

Life for the elite Peninsulares was centered within the fortified walls of Intramuros, the heart of Spanish rule in the Philippines. Intramuros was designed to be a microcosm of Spanish urban life, featuring imposing stone churches, government buildings, and elegant residences (casas de piedra). Living inside Intramuros conferred prestige and security.

The daily routine of a high-ranking Peninsular would depend on their position. The Governor-General presided over official ceremonies, attended mass at the cathedral, oversaw administrative matters at the Palacio del Gobernador, and entertained dignitaries. Members of the Real Audiencia spent their days in courtrooms and council chambers. Merchants involved in the Galleon Trade managed their warehouses and prepared for the arrival and departure of the ships.

Social life was vibrant but exclusive, largely confined to interactions among other Peninsulares, high-ranking Insulares, and senior clergy within Intramuros. Gatherings, banquets, religious festivals, and formal calls constituted the social calendar. These interactions served not only for leisure but also for networking and consolidating power and influence. Marriages often occurred within this small, elite circle, sometimes between Peninsulares and wealthy Insulares families, though intermarriage with native populations, while it created the Mestizo class, rarely elevated individuals to the highest echelons of power occupied by the pure-blooded Spaniards.

For lower-ranking Peninsulares (minor officials, military officers, less successful merchants), life might have been less grand, but they still benefited from their status and enjoyed privileges denied to non-Spaniards.

Beyond the walls of Intramuros, the experience of Peninsulares varied. Alcaldes Mayores lived in provincial capitals, wielding considerable power but potentially facing isolation or danger. Missionaries, often Peninsulares or from Spanish religious orders, lived among the native populations in remote areas, focused on conversion and establishing parishes.

Relationship with Other Groups: The Insulares Rivalry

Perhaps the most significant social and political tension within the Spanish colonial elite stemmed from the rivalry between the Peninsulares and the Insulares. The Insulares, despite being of pure Spanish blood, were systematically denied access to the highest positions simply because they were born in the colony. This created a deep-seated resentment.

The Insulares felt that their long-term residency, familiarity with local conditions, and identification with the Philippines should entitle them to leadership roles. They viewed the Peninsulares as temporary sojourners who arrived solely to enrich themselves before returning to Spain, often with little regard for the long-term welfare of the colony or its inhabitants.

This rivalry manifested in various ways:

- Political Disputes: Insulares often petitioned the Crown for equal rights in appointments, though these pleas were largely ignored.

- Economic Competition: While Peninsulares dominated the top tier of the Galleon Trade, wealthy Insulares also participated and competed in other aspects of the colonial economy.

- Social Friction: Despite intermarriage occurring, social circles could be divided, with Peninsulares sometimes looking down upon their colonial-born counterparts.

- Ideological Differences: As the colonial period progressed, some Insulares began to develop a nascent sense of identity tied to the Philippines, distinct from Spain, contributing to early nationalist sentiments.

This table highlights some key differences and points of contention:

| Feature | Peninsulares | Insulares |

|---|---|---|

| Place of Birth | Spain (Iberian Peninsula) | Spanish colonies (e.g., Philippines) |

| Access to Power | Preferred for highest government/church posts | Systematically denied highest positions |

| Perceived Loyalty | Closer to the Crown and Spain | Seen as potentially less loyal, more localized |

| Duration of Stay | Often temporary, aiming to return to Spain | Permanent residents, considered their homeland |

| Economic Advantage | Dominance in top-tier trade (Galleon Trade), monopolies | Participated in trade, land ownership, but faced barriers |

| Social Status | Apex of the social hierarchy | Below Peninsulares, despite pure Spanish blood |

Export to Sheets

The grievances of the Insulares were a significant factor in the growing discontent against Spanish rule, laying some of the groundwork for later reform and revolutionary movements. The Cavite Mutiny of 1872, for instance, involved both native soldiers and creole officers.

The relationship with the native Indio and Mestizo populations was largely one of ruler and ruled. Peninsulares benefited directly from the labor and tribute extracted from the Indios. While some friars among the Peninsulares advocated for the welfare of the natives, the general relationship was one of dominance and exploitation. The principalia, the native elite, served as intermediaries, collaborating with the Spanish authorities to maintain order and facilitate tribute collection, but remained subordinate to the Spanish officials. The Mestizos, particularly those of Spanish and native or Spanish and Chinese descent, occupied a middle ground, their status and influence depending largely on their wealth and connection to the Spanish elite. Some wealthy Mestizo families could attain a degree of influence, but the highest echelons of power remained the preserve of the Peninsulares.

Challenges to Peninsular Authority

Despite their privileged position, the Peninsulares faced various challenges throughout the colonial period:

- Corruption and Abuse of Power: The immense power wielded by Peninsulares, particularly Alcaldes Mayores, often led to corruption, extortion, and abuse of the native population. This generated resentment and occasional rebellions.

- External Threats: The Philippines was a strategic location, and Peninsulares had to contend with threats from rival European powers (Dutch, British) and persistent raids from Muslim sultanates in the south.

- Internal Dissent: Beyond native revolts and the Insulares rivalry, conflicts could arise among Peninsulares themselves due to personal rivalries, disputes over power, or disagreements on policy. The Real Audiencia sometimes clashed with the Governor-General.

- Distance from Spain: While being born in Spain was the source of their power, the vast distance meant that decisions and support from Madrid were slow in coming, requiring Peninsulares on the ground to exercise considerable autonomy, which could sometimes lead to unforeseen consequences or challenges to central authority.

The Impact of the Bourbon Reforms

The 18th century saw the implementation of the Bourbon Reforms across the Spanish Empire. These reforms, initiated by the Bourbon monarchs of Spain, aimed to centralize administration, improve efficiency, increase revenue, and assert greater control over the colonies. While intended to strengthen the empire, the Bourbon Reforms had a significant, albeit unintended, impact on the position of the Peninsulares and exacerbated tensions with the Insulares.

Key aspects of the Bourbon Reforms in the Philippines included:

- Creation of Royal Monopolies: The tobacco monopoly, established in 1782, became a major source of revenue but also led to hardship for native farmers and increased administrative presence.

- Increased Number of Peninsular Officials: The reforms often resulted in more positions being created or filled by Peninsulares sent directly from Spain, further limiting opportunities for Insulares.

- Ending the Galleon Trade: The Galleon Trade was officially ended in 1815, replaced by direct trade between the Philippines and Spain. This removed a major source of wealth and power for the Manila-based Peninsulares who controlled the boletas.

- Military Reforms: Increased emphasis on professional military forces, often led by Peninsular officers.

Ironically, by seeking to tighten control and extract more resources, the Bourbon Reforms heightened the grievances of the Insulares and other segments of the population who saw their economic opportunities curtailed and their aspirations for greater participation in governance ignored. This period saw a hardening of the lines between the Peninsulares and the colonial-born elite.

The Waning Days of Dominance and the Rise of the Ilustrados

The 19th century marked a period of significant change and the gradual erosion of the absolute dominance of the Peninsulares. Several factors contributed to this shift:

- The Opening of the Philippines to World Trade: From 1834 onwards, ports in the Philippines were gradually opened to foreign trade, ending Spain’s long-held monopoly and creating new economic opportunities outside the traditional Spanish-controlled systems like the Galleon Trade. This benefited not only foreign merchants but also local entrepreneurs, including wealthy Mestizos and principalia, whose economic power began to grow.

- The Rise of the Ilustrados: The economic changes allowed some Filipino families (primarily Insulares and wealthy Mestizos) to send their sons to study in Europe. These Ilustrados (Enlightened Ones) were exposed to liberal ideas, nationalism, and critiques of colonialism. Figures like José Rizal, Graciano López Jaena, and Marcelo H. del Pilar, though not Peninsulares themselves (they were Insulares or Mestizos), became vocal critics of Spanish rule and the injustices of the colonial system, including the preferential treatment of Peninsulares.

- Secularization Controversy: Disputes within the church between regular clergy (often Peninsulares from religious orders) and secular clergy (increasingly Insulares and native priests) added another layer of tension and highlighted the discrimination faced by the colonial-born clergy.

- Increased National Consciousness: The combined effects of economic changes, the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 (which led to the martyrdom of three secular priests: Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora, falsely accused of rebellion), and the propaganda movement led by the Ilustrados fostered a growing sense of national identity among Filipinos, uniting various groups (Insulares, Mestizos, Principalia) against Spanish rule and its agents, the Peninsulares.

While Peninsulares continued to hold the highest positions until the end of Spanish rule in 1898, their authority was increasingly challenged. The political stability they represented was undermined by growing unrest and the organization of nationalist movements like the Katipunan. The once unassailable position of the Peninsulares became a symbol of colonial oppression and a target for those seeking reform and independence.

The End of an Era and Legacy

The Spanish-American War in 1898 brought an abrupt end to over three centuries of Spanish rule in the Philippines. The Treaty of Paris ceded the archipelago to the United States. For the Peninsulares, this marked the end of their privileged era. Many returned to Spain, their power and influence in the Philippines vanishing with the colonial flag.

The departure of the Peninsulares left a vacuum at the very top of the social and political structure. This vacuum was partly filled by the rising Insulares, Mestizos, and principalia, who had, by this time, developed a stronger sense of Filipino identity and were poised to play a more prominent role in the country’s affairs, first under American colonial rule and eventually in an independent Philippines.

The legacy of the Peninsulares in the Philippines is complex and multifaceted. On one hand, they were the agents of colonialism, responsible for implementing policies that led to exploitation, cultural disruption, and the imposition of a rigid social hierarchy and racial stratification. Their pursuit of wealth through systems like the Galleon Trade primarily benefited Spain and a small elite, rather than fostering broad-based development within the Philippines.

On the other hand, they established the foundational administrative and legal systems that, in modified forms, persist to some extent today. They introduced Christianity, which became a dominant cultural force. Their architectural legacy can still be seen in places like Intramuros, although much was destroyed during World War II.

Ultimately, the life of the Filipino Peninsulares exemplifies the nature of colonial power – the imposition of foreign rule, the creation of a privileged elite based on origin, and the inherent tensions arising from such an unequal system. Their story is inextricably linked to the story of resistance, the struggle for identity, and the eventual emergence of the Filipino nation. The resentment fueled by Peninsular dominance was a significant, though not the sole, catalyst for the movements that sought to dismantle Spanish rule and establish an independent Philippines.

Understanding their role is crucial for appreciating the depth of the social and political changes that swept through the Philippines in the late 19th century and the complex factors that contributed to the birth of the nation. The hierarchical structure they sat atop, with Peninsulares at the summit, Insulares below, followed by Mestizos and Indios, shaped social relations, access to power, and economic opportunities for centuries, leaving an indelible mark on the social fabric of the Philippines.

Key Takeaways:

- Peninsulares were Spaniards born in Spain who held the highest positions in the Spanish colonial Philippines.

- They occupied the apex of a rigid social hierarchy and racial stratification system.

- Their power stemmed from control over government, military, church, and key economic activities like the Galleon Trade.

- Life for the elite Peninsulares was largely centered in Intramuros, the walled city of Manila.

- A significant rivalry existed between Peninsulares and Insulares (Spanish born in the Philippines) due to the latter’s exclusion from top posts.

- The Bourbon Reforms in the 18th century aimed to increase Spanish control but often exacerbated colonial tensions.

- The rise of the Ilustrados and increased national consciousness challenged Peninsular dominance in the 19th century.

- The end of Spanish rule in 1898 marked the end of the Peninsulares’ era of privilege in the Philippines.

- Their legacy is tied to both the imposition of colonialism and the institutional structures they established.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

- Who exactly were the Peninsulares in the context of the Philippines? Peninsulares were individuals born in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain) who resided in the Spanish colonial Philippines. They were distinct from Insulares, who were Spaniards born in the colony.

- Why did Peninsulares hold more power than Insulares? The Spanish Crown favored Peninsulares for almost all high-ranking positions in the government, military, and church based solely on their birthplace. This was part of Spain’s strategy to maintain tighter control over its colonies by appointing administrators directly from the metropole, perceived as more loyal.

- What was the significance of the Galleon Trade for the Peninsulares? The Galleon Trade between Manila and Acapulco was a major source of wealth. Peninsulares controlled access to the lucrative boletas (shipping licenses), allowing them to accumulate vast fortunes through the exchange of Asian goods for American silver.

- How did the Peninsulares interact with the native Filipino population? The relationship was primarily one of ruler and ruled. Peninsulares, as agents of Spanish rule, benefited from the tribute and labor of the native Indio population. While some missionaries advocated for native rights, the system was largely exploitative and reinforced the existing social hierarchy.

- What were the Bourbon Reforms and how did they affect Peninsulares? The Bourbon Reforms were 18th-century changes by the Spanish Crown to centralize control and increase revenue. They often led to more Peninsulares being sent to the colonies and the end of the Galleon Trade, which impacted the economic basis of some Peninsular fortunes, while simultaneously increasing the grievances of the Insulares.

- How did the rise of the Ilustrados challenge Peninsular dominance? The Ilustrados, educated Filipinos (mostly Insulares and Mestizos) exposed to liberal ideas, criticized the injustices of Spanish rule, including the favoritism shown to Peninsulares. Their writings and activism fostered a sense of national identity and fueled opposition to the colonial system the Peninsulares represented.

- What happened to the Peninsulares after Spanish rule ended? When the Philippines was ceded to the United States in 1898, the basis of the Peninsulares’ power vanished. Most returned to Spain, their era of dominance in the Philippines concluded.

- Is the term “Filipino Peninsulares” historically accurate? Historically, “Filipino” in the Spanish colonial era often referred specifically to Insulares (Spanish born in the Philippines). Peninsulares were Spaniards born in Spain. The term “Filipino Peninsulares” used in the title should be understood as “Peninsulares residing in the Philippines.”

Sources:

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. History of the Filipino People. 8th ed. Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, 1990.

- Blair, Emma Helen, and James Alexander Robertson, eds. The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898. 55 vols. Cleveland, Ohio: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1903-1909. (Contains numerous primary source documents detailing the colonial administration and social life). Available online through various digital archives.

- Corpuz, Onofre D. The Roots of the Filipino Nation. 2 vols. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1989.

- Cushner, Nicholas P. Spain in the Philippines: From Conquest to Revolution. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1997.

- Phelan, John Leddy. The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959.

- Schurz, William Lytle. The Manila Galleon. Manila: Historical Conservation Society, 1985. (Classic work on the Galleon Trade).

- Taylor, George E. The Philippines and the United States: Problems of Partnership. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964. (Provides context on the transition from Spanish to American rule).

(Note: Access to specific editions or online versions of these sources may vary. These are widely recognized academic works on Philippine history during the Spanish period.)