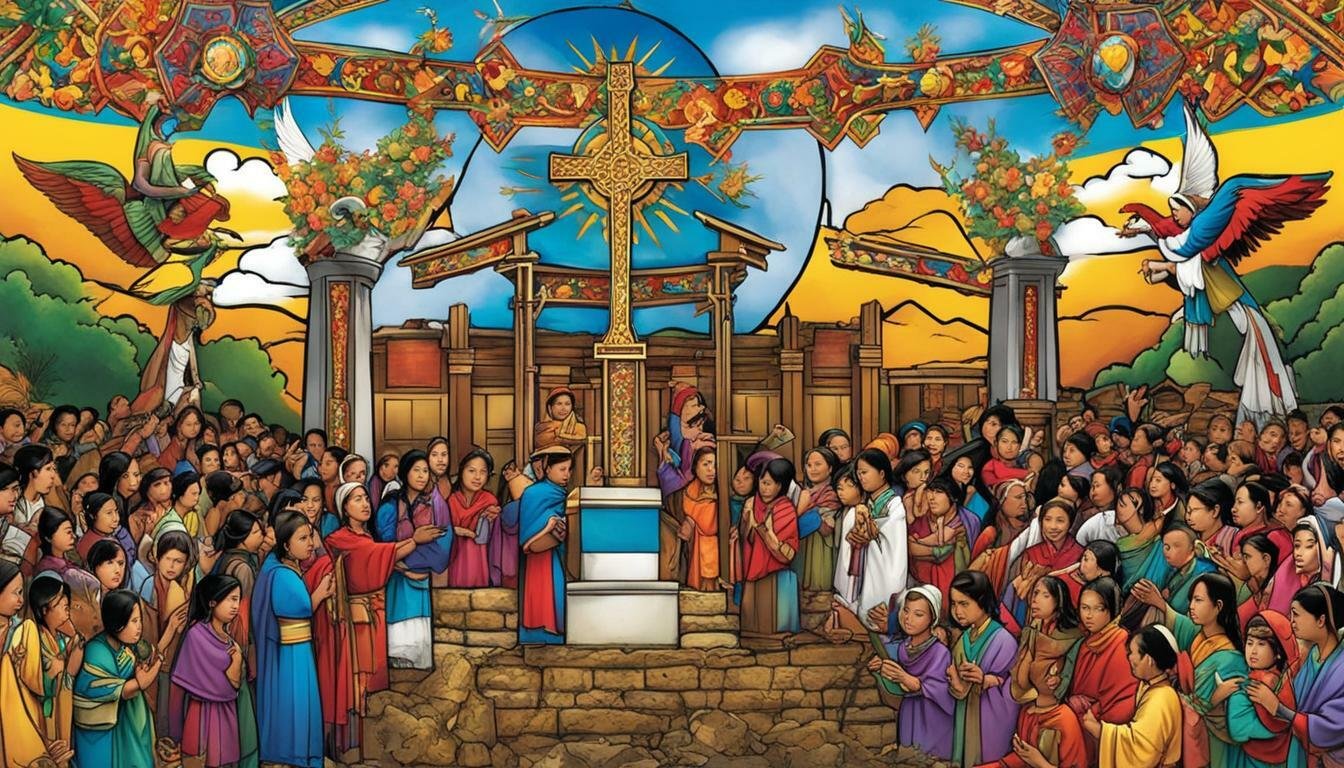

The story of the Spread of Christianity in the Philippines is inextricably linked with the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. What began as a seemingly isolated event – a cross planted on a shore – evolved over centuries into the defining cultural and spiritual characteristic of the archipelago. Today, the Philippines stands as the only predominantly Christian nation in Asia, a testament to the enduring impact of Spanish evangelization. This article delves into the historical journey of Christianity in the Philippines, tracing its introduction, the methods employed by missionaries, the challenges faced, the cultural transformations it ignited, and its evolution through different historical periods.

The Seeds of Faith: Arrival with the Spanish

The initial contact between the Philippines and European Christianity occurred with the arrival of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, sailing under the Spanish flag. His expedition, aimed at finding a western route to the Spice Islands, stumbled upon the archipelago, forever altering its destiny.

Ferdinand Magellan’s Expedition (1521)

Magellan’s arrival in Homonhon on March 16, 1521, marked the first direct contact with the local population and, subsequently, the first attempt at introducing Christianity. After establishing friendly relations with the chieftain of Limasawa, Rajah Kolambu, and his brother, Rajah Siagu, the first Mass in the Philippines was celebrated on Easter Sunday, March 31, 1521. This event, a cornerstone of Filipino Catholic history, symbolized the formal introduction of the new faith.

Following this, Magellan proceeded to Cebu, a thriving port settlement. Here, he met Rajah Humabon, the ruler of Cebu, and managed to forge an alliance. Utilizing a strategy that combined diplomacy, demonstrations of European technology (like cannons), and religious persuasion, Magellan successfully convinced Rajah Humabon, his consort Hara Amihan, and their followers to convert to Christianity. On April 14, 1521, a mass baptism was held, with Hara Amihan reportedly given the name Juana (after the mother of Charles V) and Rajah Humabon named Carlos (after the king). Estimates vary, but historical accounts suggest thousands of Cebuanos were baptized during this period.

During this time, Magellan presented a small wooden image of the Child Jesus, known as the Santo Niño, to Hara Amihan as a baptismal gift. This act would prove profoundly significant centuries later.

However, the initial phase of evangelization was short-lived. Magellan’s involvement in a local dispute between Rajah Humabon and Lapu-Lapu, the chieftain of Mactan, led to the Battle of Mactan on April 27, 1521, where Magellan was killed. His death and the subsequent withdrawal of the remaining expedition members left the newly baptized community in Cebu without guidance, and the initial Christian presence essentially vanished.

Failed Attempts and Renewed Efforts (1525-1546)

Despite Magellan’s failure to complete his circumnavigation and establish a permanent Spanish presence, the potential of the archipelago as a source of spices and a site for evangelization was recognized by the Spanish crown. Several subsequent expeditions were dispatched, though none succeeded in establishing a lasting colony during this period:

- Loaisa Expedition (1525): Led by García Jofre de Loaisa, this expedition faced immense hardship, including the death of Loaisa and other leaders, and failed to establish a foothold.

- Saavedra Expedition (1527): Sent from Mexico under Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón, this expedition also met with limited success and was eventually forced to return.

- Villalobos Expedition (1542): Ruy López de Villalobos reached Mindanao and named the islands “Las Islas Filipinas” in honor of Prince Philip of Asturias (later King Philip II). However, like its predecessors, it failed to establish a permanent settlement due to lack of supplies and Portuguese hostility in the region.

While these expeditions were primarily driven by economic and strategic goals, they carried chaplains, indicating the ongoing intent of the Spanish crown, supported by the Patronato Real (the royal patronage system that granted the Spanish monarchs significant control over the Church in their territories), to spread Catholicism. However, without a sustained presence, the seeds of faith planted during Magellan’s visit lay dormant.

Legazpi’s Successful Colonization (1565)

The turning point came with the expedition led by Miguel López de Legazpi, which arrived in Cebu in 1565. Unlike previous attempts, Legazpi’s mission was explicitly focused on colonization and evangelization.

Upon arriving in Cebu, Legazpi and his men faced resistance but eventually managed to establish a settlement. A pivotal moment occurred when a soldier discovered the image of the Santo Niño amidst the ruins of a burnt house, remarkably preserved from Magellan’s time. This was seen as a miraculous sign, bolstering the morale of the Spanish and serving as a potent symbol for the re-introduction of Christianity. The first church in the Philippines, dedicated to the Santo Niño, was built on this site.

Legazpi’s strategy involved a combination of military force, diplomacy, and the crucial work of the missionaries. The Augustinian friars who accompanied Legazpi played an immediate and vital role in initiating the systematic process of conversion. From Cebu, the Spanish gradually expanded their control, moving to Panay and eventually conquering the fortified kingdom of Manila in 1571. The fall of Manila, under Rajah Sulayman, marked the establishment of the Spanish capital and accelerated the Spread of Christianity in the Philippines.

The Pillars of Evangelization: Missionary Orders

The systematic and widespread evangelization of the archipelago was primarily carried out by various religious orders, often referred to collectively as friars. These orders arrived in waves and were assigned specific territories to administer, preach, and convert the local population.

The Arrival of the Friars

The principal missionary orders responsible for the initial and sustained Spread of Christianity in the Philippines were:

- Augustinians: Arrived with Legazpi in 1565. They were the pioneers and established some of the earliest and most important parishes.

- Franciscans: Arrived in 1578. Known for their simplicity and dedication to the poor.

- Jesuits: Arrived in 1581. Focused on education and intellectual pursuits, establishing prominent colleges.

- Dominicans: Arrived in 1587. Known for their theological rigor and defense of indigenous rights (though often in complex ways).

- Augustinian Recollects: Arrived in 1606. Worked in various challenging frontier areas.

These orders, often competing for influence and resources, were the backbone of the colonial administration’s spiritual mission. They were not just religious figures but also acted as administrators, builders, educators, and cultural intermediaries.

Evangelization Strategies and Challenges

The missionaries employed a variety of strategies to achieve conversion:

- Learning Indigenous Languages: Recognizing the necessity of communication, friars dedicated themselves to learning the diverse languages of the archipelago (Tagalog, Visayan, Ilokano, etc.). They produced dictionaries, grammars, and catechisms in these languages, such as the Doctrina Christiana (1593), the first book printed in the Philippines, which contained basic Christian prayers and teachings in Spanish and Tagalog. This was crucial for effective preaching and instruction.

- Building Churches and Convents: The construction of stone churches and convents served as visible symbols of the new faith and centers for community life. These structures often incorporated local materials and labor, and their impressive scale aimed to inspire awe and reverence. Many of these colonial churches still stand today and are architectural treasures.

- Reducción System: One of the most significant and often controversial strategies was the Reducción system. This involved the forced resettlement of scattered indigenous populations into planned villages (cabeceras) centered around a church and a plaza. The goal was to bring the people together for easier administration, taxation, and, crucially, Christian instruction and mass attendance. While it facilitated evangelization, it disrupted traditional community structures and ways of life, sometimes leading to resistance.

- Adaptation and Appropriation: Missionaries sometimes incorporated elements of existing Indigenous beliefs and practices into Christian rituals to make the new faith more palatable and understandable. This contributed to the development of religious syncretism, where indigenous concepts found parallels or were subtly integrated into Catholic practices.

- Education: Establishing schools, initially for the children of the native elite (principales), helped train future leaders in Christian doctrine and Spanish culture. These institutions, like those founded by the Jesuits and Dominicans, became centers of colonial learning.

However, the process was not without its challenges. Missionaries faced:

- Resistance: Many indigenous communities, particularly those with strong existing social structures and beliefs, resisted the imposition of Spanish rule and Christianity. This resistance manifested in various ways, from outright revolts (like the Tamblot Revolt in Bohol in 1621, partly fueled by religious grievances, or the Bankaw Revolt in Leyte) to passive non-compliance and the continuation of traditional practices in secret.

- Geographical Difficulties: The dispersed nature of the islands and the challenging terrain made it difficult to reach and minister to all communities effectively.

- Shortage of Missionaries: Despite the influx of religious orders, there were never enough missionaries to cover the vast territory and population adequately.

- Cultural and Linguistic Barriers: Despite efforts to learn local languages, nuances and deep-seated cultural understandings sometimes posed significant barriers to genuine conversion rather than superficial adoption.

- Conflicts with Civil Authorities: The friars, holding significant power and influence, often clashed with the colonial civil governors over jurisdiction, land, and treatment of the indigenous population. These conflicts could complicate the mission.

- Internal Challenges: Maintaining discipline and fervor within the missionary orders themselves was also a constant challenge.

Establishing the Church Hierarchy and Institutions

As the Spanish established control, they also built the formal structure of the Catholic Church in the Philippines, creating dioceses, parishes, and educational institutions that would solidify the Spread of Christianity in the Philippines.

Dioceses and Parishes

The first diocese was established in Manila in 1579, initially a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Mexico. It was later elevated to an Archdiocese in 1595, with Manila becoming the ecclesiastical center of the islands. Subsequent dioceses were created in key regional centers:

- Diocese of Cebu (1595): Reflecting the importance of the site of the first landing and settlement.

- Diocese of Nueva Segovia (now in Luzon, 1595): Covering northern Luzon.

- Diocese of Nueva Cáceres (now Naga, 1595): Covering southeastern Luzon.

These dioceses were further subdivided into parishes, each centered around a church and administered by a parish priest, typically a friar from one of the orders. The parish priest became a powerful figure at the local level, often the only Spaniard living among the indigenous population, wielding both spiritual and sometimes civil authority. The sheer number and influence of the regular clergy (friars) in parishes became a major issue later in the colonial period.

Education and Social Services

The religious orders were instrumental in establishing the first formal educational institutions in the Philippines, initially to train priests and administrators and later to educate the local elite.

- Colegio de San Ildefonso (Cebu, 1595): Founded by the Jesuits, it is one of the oldest educational institutions in Asia.

- Colegio de San José (Manila, 1601): Also founded by the Jesuits, another pioneering institution.

- University of Santo Tomas (Manila, 1611): Founded by the Dominicans, it is the oldest existing university in Asia and played a central role in intellectual and religious life.

These institutions, while primarily serving the Spanish and Creole populations and the native elite, gradually became avenues for limited social mobility and the dissemination of European knowledge and values, including Christian doctrine.

Beyond education, the Church also established hospitals, orphanages, and other charitable institutions, reflecting the Christian emphasis on care for the poor and needy. These services, while often insufficient to meet the widespread needs, further cemented the Church’s role in colonial society.

The Evolution of Philippine Catholicism

Over centuries, the practice of Catholicism in the Philippines evolved from a foreign import into a distinctly Filipino form, shaped by the interaction between Spanish doctrine and existing Indigenous beliefs and cultural practices.

Religious Syncretism

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Spread of Christianity in the Philippines is the phenomenon of religious syncretism. Rather than a complete replacement of old beliefs, Christianity was often integrated into existing worldviews. Examples include:

- Veneration of Saints and Images: The Catholic devotion to saints found resonance with pre-colonial beliefs in anitos or spirits associated with specific places or aspects of nature. Statues of saints (santos) sometimes took on roles similar to those of indigenous idols, becoming mediators or protectors. The deep devotion to the Santo Niño, in particular, echoes pre-colonial veneration of powerful child figures or spirits.

- Rituals and Festivals: Catholic festivals, such as the fiesta celebrating the patron saint of a town, often incorporated pre-colonial communal feasting and celebratory traditions. Elements of animistic rituals sometimes found their way into processions or local religious practices. The concept of a supreme being in indigenous religions could be somewhat aligned with the Christian God, but the pantheon of lesser deities or spirits was often reinterpreted through the lens of saints, angels, or even demons.

- Beliefs in the Supernatural: Christian concepts of heaven, hell, angels, and demons were layered onto or blended with existing beliefs in the spirit world, witchcraft (barang), and various mythical creatures.

The Boxer Codex, a late 16th-century manuscript illustrating the peoples of Southeast Asia, including detailed depictions of the Tagalogs, Visayans, and other groups in the Philippines before extensive Spanish influence, provides valuable insights into the rich tapestry of pre-colonial Indigenous beliefs and practices, offering a baseline against which to understand the transformations wrought by evangelization and religious syncretism.

Cultural and Artistic Impact

The Church profoundly influenced Filipino culture and art.

- Architecture: Churches became the most prominent buildings in towns, built in various styles (Baroque, Neoclassical), often adapted to the local climate and seismic conditions (Earthquake Baroque).

- Religious Art: The production of religious images (santos), paintings, and retablos flourished, incorporating Filipino craftsmanship and sometimes subtle local interpretations of religious figures.

- Music and Performing Arts: Christian narratives were incorporated into local performing arts traditions. The pasión, a narrative of Christ’s life and suffering, is sung during Holy Week. The senakulo, a dramatic re-enactment of the Passion, remains a popular tradition.

- Literary Works: Early printed materials, like the Doctrina Christiana, were religious. Later, religious themes permeated Filipino literature, including devotional works and narratives with moral lessons.

The Church and Colonial Society

The Church was not merely a spiritual force; it was an integral part of the colonial administration and significantly influenced the social and political landscape of the Philippines.

Political Influence of the Friars

The friars, particularly the parish priests, held immense power at the local level. They were often the de facto authorities in remote areas, acting as advisors to the native leaders (gobernadorcillos), overseeing public works, controlling education, and even influencing appointments. Their knowledge of local languages and customs gave them unique leverage.

This power, coupled with the immense wealth accumulated by the religious orders through land ownership (friar lands), led to frequent conflicts with both the colonial civil government and the Filipino population. The Patronato Real theoretically subjected the clergy to royal authority, but in practice, the friars often operated with considerable autonomy.

The pervasive influence and perceived abuses of the friars became a major source of discontent among Filipinos in the 19th century, fueling anti-clerical sentiments that were a significant factor leading to the Philippine Revolution. Events like the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 and the subsequent execution of the GomBurZa (Fathers Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora), three Filipino secular priests falsely accused by the Spanish authorities, were deeply intertwined with the struggle between the Filipino secular clergy and the powerful Spanish friar orders.

Social Stratification and Religious Practice

The Church played a role in the social stratification of the colony. While Christianity was open to all, access to education and positions within the Church hierarchy was initially limited. The native elite, who converted early, often gained privileges and influence. The Reducción system also altered social dynamics by reorganizing communities.

Religious practice became a central part of daily life, marking the rhythm of the day, week, and year with prayers, masses, sacraments, and festivals. While some conversions were undoubtedly sincere, others were likely motivated by a desire to gain favor with the Spanish, avoid punishment, or adapt to the new social order.

Christianity Under New Rule (American Period and Beyond)

The end of Spanish rule with the Spanish-American War in 1898 and the subsequent American colonization brought new dynamics to the Spread of Christianity in the Philippines.

Introduction of Protestantism

The American period saw the arrival of various Protestant denominations, including Methodists, Presbyterians, Baptists, and others. Unlike the unified approach of the Spanish Catholic Church, the Americans introduced religious pluralism. Protestant missionaries established schools, hospitals, and churches, often focusing on social reform alongside evangelization. While Catholicism remained the dominant religion, Protestantism gained a foothold, particularly in urban areas and among certain sectors of the population.

The Iglesia ni Cristo

The early 20th century also saw the rise of indigenous Christian movements. The most prominent of these is the Iglesia ni Cristo, founded by Felix Manalo in 1914. This movement, distinct from mainstream Catholicism and Protestantism, emphasizes specific doctrines and has grown into a significant religious force in the country.

Catholicism in the 20th and 21st Centuries

Philippine Catholicism continued to evolve throughout the 20th century. A significant development was the Filipinization of the clergy, with increasing numbers of Filipino priests and eventually bishops taking leadership roles. The Second Vatican Council (Vatican II, 1962-1965) had a profound impact on the global Catholic Church, including in the Philippines. Its emphasis on liturgical reforms, increased lay participation, ecumenism, and social justice resonated with the local Church and influenced its direction.

The Catholic Church has played a prominent role in modern Philippine history, notably during the EDSA People Power Revolution in 1986, where it provided moral leadership and mobilized popular support against the Marcos regime. Today, the Church remains a powerful social and political force, actively involved in various issues.

Challenges and Diversity in the Spread of Faith

Despite the pervasive Spread of Christianity in the Philippines, particularly Catholicism, the process was not uniform, and significant diversity exists.

Resistance and Revolts

As mentioned earlier, various revolts throughout the Spanish period were partly driven by resistance to religious impositions, the Reducción system, or the abuses of the friars. While these revolts were ultimately suppressed, they demonstrate that conversion was not always peaceful or voluntary.

Moreover, the predominantly Muslim populations in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago largely resisted Spanish attempts at conquest and conversion, maintaining their Islamic faith and distinct cultural identity. This historical resistance continues to shape the religious and political landscape of the southern Philippines.

Conversion Among Indigenous Peoples

The evangelization of scattered and diverse Indigenous peoples across the archipelago presented unique challenges. While many lowland groups were eventually integrated into the Catholic fold through the Reducción system and missionary efforts, some upland and remote communities maintained more of their traditional beliefs and practices. Missionary work continues among these groups today, often with a greater emphasis on cultural sensitivity and dialogue, though challenges remain in balancing evangelization with respect for indigenous cultures and self-determination.

The legacy of the Spread of Christianity in the Philippines among Indigenous peoples is complex, involving both the loss of traditional ways and the adaptation of Christian faith within existing cultural frameworks.

Conclusion

The Spread of Christianity in the Philippines is a multi-faceted historical narrative spanning over four centuries. It began with the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan and was systematically pursued by Miguel López de Legazpi and waves of missionaries from various religious orders, including the Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, Dominicans, and Augustinian Recollects. Their efforts, facilitated by the Patronato Real and strategies like the Reducción system, fundamentally transformed the archipelago.

While the initial phase in Cebu, marked by the arrival of the Santo Niño and the first baptisms, was interrupted, Legazpi’s successful colonization in 1565 established a permanent Spanish presence and allowed for sustained evangelization. The Church hierarchy was built, with Manila Cathedral becoming a key symbol of its institutional power, and essential texts like the Doctrina Christiana were produced.

The interaction between imported Catholicism and existing Indigenous beliefs led to widespread religious syncretism, creating a unique Filipino form of Catholicism that blended foreign dogma with local customs. The Church’s influence extended beyond the spiritual, deeply impacting Filipino culture, art, education, and social structures. However, the power and wealth of the friars also contributed to social tensions that played a role in the Philippine Revolution.

The American period introduced Protestantism and religious pluralism, adding another layer to the country’s religious landscape. Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the Catholic Church continued to adapt, influenced by events like Vatican II, and has remained a significant force in national life.

Despite the dominance of Catholicism, particularly among lowland Christian Filipinos, the Philippines remains a religiously diverse nation, with a substantial Muslim population and various indigenous belief systems. The history of the Spread of Christianity in the Philippines is a complex tapestry of conversion, resistance, adaptation, and the enduring search for spiritual meaning that continues to shape the nation’s identity.

Key Takeaways:

- Christianity was introduced to the Philippines by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, with the first mass and baptisms in Cebu.

- Sustained evangelization began with Miguel López de Legazpi in 1565 and was primarily carried out by various missionaries (Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, Dominicans, Augustinian Recollects).

- Key strategies included learning local languages, building churches, establishing the Reducción system, and utilizing the Patronato Real.

- The Church established a hierarchical structure, including dioceses in Manila and Cebu, and founded important educational institutions.

- Religious syncretism led to a unique blend of Catholic and Indigenous beliefs.

- The influence and perceived abuses of the friars were a significant factor in the Philippine Revolution.

- The American period introduced Protestantism and religious pluralism.

- Vatican II significantly impacted Philippine Catholicism in the latter half of the 20th century.

- Resistance from groups like Muslim Filipinos and some Indigenous peoples demonstrates the non-uniform nature of conversion.

- Artifacts like the Santo Niño, Boxer Codex, and Doctrina Christiana provide insights into the historical context and cultural impact.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

- When did Christianity first arrive in the Philippines? Christianity first arrived in the Philippines with the expedition of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521.

- Who were the main groups responsible for spreading Catholicism? The main groups were the missionaries from various religious orders, particularly the Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, Dominicans, and Augustinian Recollects, who arrived during the Spanish colonial period.

- What is the significance of the Santo Niño? The Santo Niño image was a gift from Ferdinand Magellan to the Queen of Cebu in 1521. Its rediscovery in 1565 by Legazpi’s expedition was seen as a miraculous sign and became a powerful symbol for the re-establishment and Spread of Christianity in the Philippines. It remains a central figure of devotion for Filipino Catholics.

- What was the Reducción system? The Reducción system was a Spanish colonial policy that forcibly resettled dispersed indigenous populations into concentrated villages centered around a church and plaza. This system was implemented to facilitate colonial administration, taxation, and evangelization.

- How did Indigenous beliefs interact with Catholicism? Rather than being completely replaced, Indigenous beliefs often blended with Catholic practices, leading to religious syncretism. This is evident in the veneration of saints, the adaptation of festivals, and the integration of traditional spirit beliefs into a Christian framework. The Boxer Codex offers insights into the pre-colonial beliefs that influenced this syncretism.

- What role did the friars play in the Philippine Revolution? The significant power, wealth, and perceived abuses of the Spanish friars were major sources of discontent among Filipinos in the 19th century. Anti-clerical sentiment fueled the Philippine Revolution, as Filipinos sought greater autonomy and challenged the dominance of the religious orders.

- What happened to Christianity in the Philippines during the American period? The American period saw the introduction of Protestantism by American missionaries, leading to greater religious diversity. While Catholicism remained dominant, various Protestant denominations established a presence.

- What is the importance of the Doctrina Christiana? The Doctrina Christiana (1593) is historically significant as the first book printed in the Philippines. It contained basic Christian teachings in Spanish and Tagalog, serving as a key tool for early evangelization.

- How did Vatican II affect the Catholic Church in the Philippines? Vatican II (1962-1965) introduced reforms that led to changes in liturgy, increased lay participation, a greater focus on social justice, and dialogue with other religions. These reforms influenced the direction of the Catholic Church in the Philippines in the latter half of the 20th century and beyond.

- Is the entire Philippines Christian? No, while the Philippines is predominantly Christian, with Catholicism being the largest denomination, there is a significant Muslim population, particularly in Mindanao, as well as various indigenous belief systems and other religious groups.

Sources:

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. History of the Filipino People. 8th ed. Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, 1990. (A widely cited textbook on Philippine history).

- Arcilla, José S. An Introduction to Philippine History. 5th ed. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2008. (Provides a solid overview of the colonial period and the role of the Church).

- Blair, Emma Helen, and James Alexander Robertson, eds. The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. 55 vols. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1903–1909. (A massive collection of translated primary source documents from the Spanish colonial era, including missionary accounts). Available online via Project Gutenberg or the University of Michigan’s Philippine History Collection.

- Cano, Gaspar. Catálogo de los religiosos de N.S.P. Agustín de la provincia del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús de Filipinas: desde su establecimiento en estas Islas hasta nuestros días: con algunas noticias biográficas de los mismos. Manila: Imp. de Ramirez y Giraudier, 1893. (Historical catalogue of Augustinian friars in the Philippines).

- De la Costa, Horacio. The Jesuits in the Philippines, 1581-1768. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961. (A key work on the role of the Jesuit order).

- Lach, Donald F., and Edwin J. Van Kley. Asia in the Making of Europe. Vol. III, A Century of Advance. Book 3, Southeast Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. (Provides broader context of European expansion and missionary activities in Southeast Asia).

- Phelan, John Leddy. The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959. (A classic analysis of the early colonial period and the process of cultural transformation, including evangelization).

- Rodriguez, Agustin. Historia de la Provincia Agustiniana del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús de Filipinas. 1965. (Centennial history of the Augustinians in the Philippines).

- Schumacher, John N. The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creators of a Filipino Consciousness, the Makers of the Revolution. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1997. (Discusses the role of anti-clericalism in the lead-up to the Revolution).

- Scott, William Henry. Cracks in the Parchment Curtain and Other Essays in Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1982. (Essays that offer insights into Philippine society before and during the early colonial period, using primary sources like the Boxer Codex).

- The Boxer Codex (c. 1590). Original held at the Lilly Library, Indiana University. Various scholarly editions and reproductions exist.

- The Doctrina Christiana (1593). Facsimile editions are available.

- Zaide, Gregorio F. Philippine Political and Cultural History. Rev. ed. Manila: Philippine Education Co., 1957. (Another foundational text in Philippine historiography).