The Philippines is an archipelago nation renowned for its rich tapestry of cultures, a vibrant mosaic woven from centuries of migration, trade, and interaction. Among the many indigenous groups that contribute to this diversity are the Mandaya people, primarily residing in the provinces of Davao Oriental and Davao de Oro in the southeastern part of Mindanao. Often referred to collectively as part of the Lumad groups of Mindanao, the Mandaya hold a distinct place in the ethnography and history of the Philippines, possessing a unique cultural heritage, a deep connection to their ancestral domain, and a history shaped by both internal dynamics and external forces, particularly during the periods of Spanish colonization and the American period.

Understanding the Mandaya Tribe of the Philippines requires delving into their pre-colonial life, their social structures led by datus, their spiritual beliefs rooted in animism, and their remarkable resilience in preserving their traditional culture amidst centuries of change. This article aims to provide a comprehensive historical analysis of the Mandaya, exploring their origins, societal organization, interactions with colonial powers, the challenges they face in the modern era, and their lasting contributions to the cultural landscape of the Philippines.

Origins and Early History: Roots in Eastern Mindanao

The origins of the Mandaya people are deeply intertwined with the ancient history of Eastern Mindanao. Their name is believed to be derived from “man” (person) and “daya” (upstream or upriver), signifying “people living upstream” or “people of the interior.” This etymology reflects their historical settlement patterns, typically in the mountainous and inland areas of what are now Davao Oriental and Davao de Oro.

Prior to extensive external contact, the Mandaya lived in relative isolation, their lives dictated by the rhythms of nature and the exigencies of survival in a tropical environment. Their economy was based primarily on swidden farming (kaingin), hunting, fishing, and gathering forest products. This subsistence mode fostered a close relationship with their environment, deeply influencing their spiritual beliefs and social practices. Their ancestral domain, encompassing vast tracts of forests, rivers, and mountains, was not merely a physical space but a sacred landscape teeming with spirits and ancestral energies.

Early accounts and anthropological studies suggest a decentralized political structure in the pre-colonial Mandaya society. Leadership was often vested in datus, hereditary or influential leaders who held authority within their specific communities or kinship groups. These datus were not absolute rulers but rather figures who commanded respect and loyalty based on their wisdom, bravery, wealth, and ability to settle disputes and lead in times of conflict. The concept of the bagani, or warrior-chief, was also significant, particularly in areas prone to inter-tribal conflict or raiding.

The Mandaya language, or Mandaya language, is part of the broader Austronesian language family, with various dialects spoken across their traditional territories. Language served not only as a tool for communication but also as a repository of their history, oral traditions, epics (like the “Davao”), and cultural knowledge.

Social Structure and Traditional Culture

The social fabric of the Mandaya people was intricate, based primarily on kinship and communal living. The banwa or buyawan served as the basic community unit, consisting of several households often related by blood or marriage. Within these communities, social hierarchy, while not as rigid as in some other pre-colonial Philippine societies, was present, with the datus occupying the upper strata.

Beyond the datus and their families, Mandaya society included free individuals, warriors (bagani), and sometimes a class of dependents or captives. Social mobility was possible, particularly for brave warriors or those who accumulated wealth.

Religion and spirituality were central to the traditional culture of the Mandaya. Their belief system was a form of animism, where spirits were believed to inhabit the natural world – trees, rivers, mountains, and even everyday objects. They worshipped a pantheon of deities, with Magbabaya often considered the supreme being. Rituals, ceremonies, and offerings were performed to appease or seek the favor of these spirits and deities, often mediated by spiritual leaders or shamans known as baylan. These rituals played a crucial role in agricultural cycles, healing, and navigating life’s transitions.

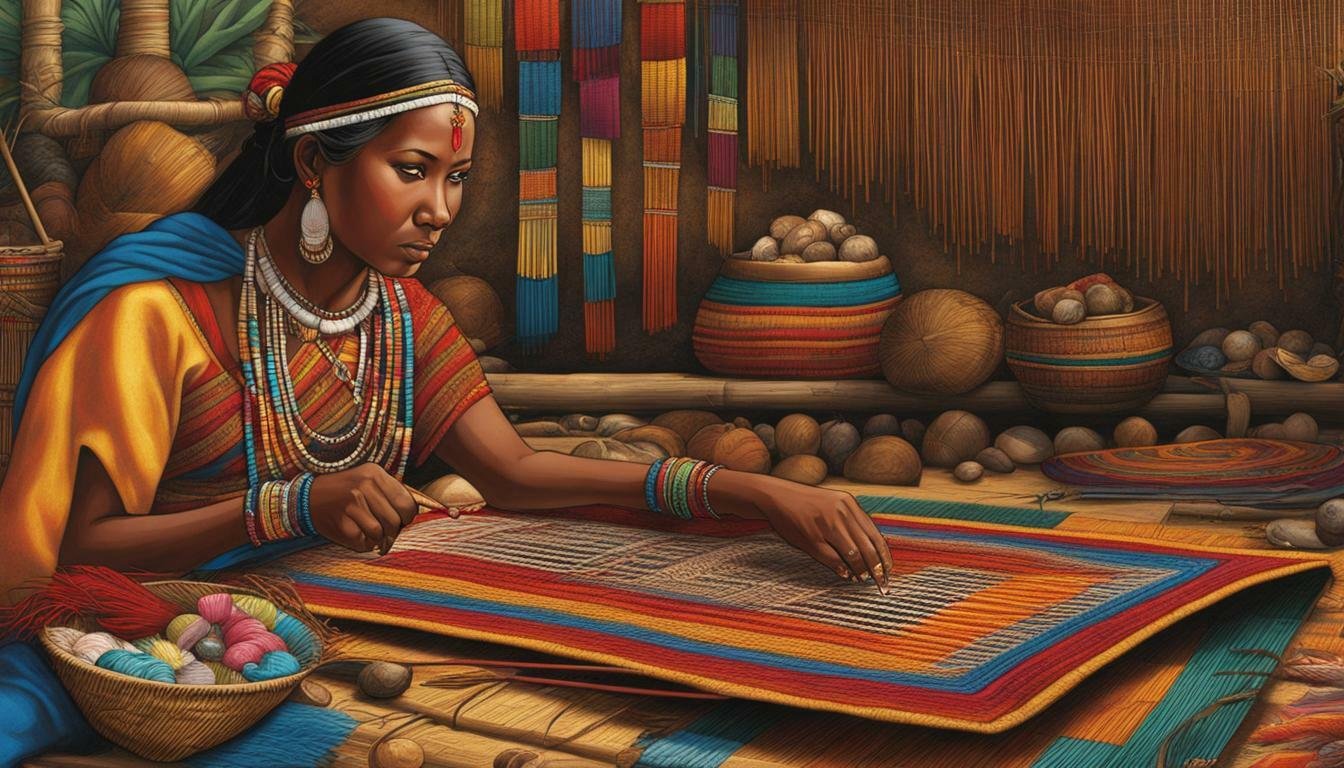

Artistic expression was another vital aspect of Mandaya culture. They are particularly renowned for their intricate weaving, especially of abaca fiber (Manila hemp) into beautiful and durable textiles known as dagmay. These textiles, often colored with natural dyes, feature complex geometric patterns, human figures, and animal motifs, each carrying symbolic meaning related to their beliefs and history. Weaving was not just a craft but a form of storytelling and cultural transmission.

Other traditional crafts included metalworking (particularly the crafting of bladed weapons like the kris and kampilan), beadwork, and pottery. Music and dance were also integral to their social and religious life, performed during celebrations, rituals, and gatherings. Their traditional attire, adorned with intricate embroidery, beads, and brass bells, reflected their aesthetic sensibilities and social status.

Interaction with Colonial Powers

The arrival of the Spanish in the Philippines in the 16th century marked the beginning of significant external influence on the indigenous groups of the archipelago, including those in Mindanao history. However, the impact of Spanish colonization on the Mandaya Tribe of the Philippines was initially limited and less profound compared to the lowland Christianized populations in Luzon and Visayas.

Spanish presence in southeastern Mindanao was primarily focused on coastal areas and was characterized by attempts at missionary work and occasional military expeditions. The mountainous terrain and the relatively remote location of the Mandaya territories provided a natural buffer against immediate and complete subjugation. While Spanish missionaries did attempt to establish contact and introduce Christianity, conversion efforts were slow and met with varying degrees of resistance or indifference. The Mandaya largely held on to their animism and traditional spiritual practices.

The Spanish administration’s primary interest in the region often revolved around controlling trade routes and preventing Moro raids from the south, rather than fully integrating the scattered and often resistant Lumad communities into their colonial system. This allowed the Mandaya to maintain a significant degree of autonomy during much of the Spanish period.

The shift in colonial power from Spain to the United States at the turn of the 20th century, following the Spanish-American War, ushered in the American period. The American approach to governing the indigenous groups of Mindanao, often referred to as “non-Christian tribes,” was different from the Spanish. The Americans aimed for greater integration through education, infrastructure development, and the introduction of new administrative structures.

During the American period, more extensive contact was made with the Mandaya and other Lumad groups. This brought about changes in their traditional way of life, including the introduction of new crops, tools, and concepts of land ownership. The American government established reservations and attempted to settle nomadic groups, often leading to disruption of traditional ancestral domain patterns and increased interaction, and sometimes conflict, over land rights. American anthropologists also conducted studies on the Mandaya, documenting aspects of their culture, language, and social organization, providing valuable, albeit sometimes biased, records.

While the Americans brought some improvements in healthcare and education, their policies also had unintended consequences, further eroding traditional authority structures and exposing the Mandaya to external economic forces. The concept of private property, alien to their communal land use, became a source of future conflict and displacement.

Resistance and Adaptation

Throughout both the Spanish colonization and the American period, the Mandaya people, like many indigenous groups, demonstrated remarkable resilience through various forms of resistance and adaptation. Direct armed resistance, though perhaps not as large-scale or well-documented as some other revolts in Philippine history, did occur in response to perceived threats to their autonomy, ancestral domain, or way of life.

More often, resistance took subtler forms, such as passive non-compliance with colonial regulations, withdrawal into more remote areas, or the selective adoption and adaptation of external influences while retaining core cultural practices. The strong leadership of datus and the spiritual guidance of the baylan played crucial roles in mobilizing communities and preserving cultural identity.

The Mandaya also adapted to the changing socio-political landscape. They learned to navigate the colonial legal systems, albeit with difficulty, particularly concerning land rights. Some individuals engaged in trade with outsiders, incorporating new goods and economic activities into their lives. Educational opportunities, though limited, allowed some Mandaya to gain literacy and engage with the wider Philippine society on new terms.

Cultural preservation efforts were often organic, passed down through generations through oral traditions, rituals, and the continued practice of traditional crafts like weaving. Despite pressures to assimilate, the Mandaya language, their belief in animism, and their intricate social customs persisted.

The post-colonial era brought new challenges, including increased migration into their territories, resource extraction activities, and further issues related to land rights and political representation. The history of the Mandaya people in the 20th and 21st centuries is one of continued struggle for self-determination, recognition of their indigenous rights, and the preservation of their unique cultural heritage in the face of modernization and external pressures.

Contemporary Mandaya Society and Challenges

Today, the Mandaya Tribe of the Philippines continues to inhabit their traditional territories in Davao Oriental and Davao de Oro. While many have integrated into mainstream Philippine society, adopting modern lifestyles and participating in the national economy and political system, a significant number still strive to maintain their cultural identity and traditional way of life.

The challenges facing contemporary Mandaya society are multifaceted. Issues related to land rights remain paramount. Encroachment by logging companies, mining operations, agricultural plantations, and settlers has led to displacement, environmental degradation within their ancestral domain, and loss of access to traditional resources. Securing and delineating their ancestral lands under the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997 is a crucial ongoing struggle.

Cultural preservation is another significant concern. The younger generation’s exposure to mainstream media, education systems, and migration to urban areas can lead to a decline in the use of the Mandaya language, the knowledge of traditional customs, and the practice of crafts like weaving. Efforts by Mandaya elders, cultural workers, and non-governmental organizations are underway to revitalize cultural practices, document oral traditions, and promote the use of their language.

Economic development within Mandaya communities is often hindered by lack of infrastructure, limited access to markets, and insufficient support for sustainable livelihoods. While some engage in cash cropping, many still rely on traditional farming methods, which can be vulnerable to environmental changes and market fluctuations.

Political representation and participation are also areas of focus. Ensuring that the voices and concerns of the Mandaya people are heard and addressed at local and national levels is vital for their self-determination and the protection of their rights.

Despite these challenges, the Mandaya people are actively working towards a future that honors their past. Community-based initiatives, cultural centers, educational programs focused on indigenous knowledge, and advocacy for indigenous rights are all part of their ongoing efforts to build a sustainable and culturally vibrant future. Their inclusion under the umbrella term Lumad has also facilitated broader alliances and collective action among indigenous groups in Mindanao.

Mandaya Contribution to Philippine History and Culture

The Mandaya Tribe of the Philippines has made significant, though often underrecognized, contributions to the broader tapestry of Philippine history and culture. Their rich oral traditions, including epics and folktales, offer invaluable insights into the pre-colonial worldview, beliefs, and social structures of indigenous Mindanao. These narratives are not just stories but historical records, albeit in a different form, preserving the memory of their ancestors and their interactions with the world around them.

Their artistic heritage, particularly their sophisticated weaving techniques and the intricate designs of their dagmay textiles, is a testament to their creativity and cultural depth. These textiles are highly prized today and are recognized as a significant part of the Philippines’ material culture and artistic legacy. The symbolism embedded in their patterns provides a unique visual language that speaks to their history and beliefs.

The resilience of the Mandaya people in maintaining their cultural identity despite centuries of external pressure and colonization serves as an inspiring example of the strength and adaptability of indigenous groups. Their continued struggle for land rights and self-determination is a crucial part of the ongoing narrative of Mindanao history and the broader fight for indigenous rights in the Philippines and globally.

Their traditional ecological knowledge, developed over generations of living in harmony with their ancestral domain, offers valuable lessons in sustainable resource management and conservation, particularly relevant in the face of contemporary environmental challenges.

In essence, the history and culture of the Mandaya people provide a vital perspective on the diverse heritage of the Philippines, challenging a singular narrative and highlighting the importance of recognizing and celebrating the unique contributions of each indigenous group.

Key Takeaways:

- The Mandaya Tribe of the Philippines are an indigenous group primarily located in Davao Oriental and Davao de Oro in Eastern Mindanao, part of the broader Lumad classification.

- Their traditional society was organized around kinship groups led by datus and characterized by animism and a strong connection to their ancestral domain.

- They possessed a rich traditional culture, particularly known for their intricate weaving of dagmay textiles and the role of the bagani.

- Spanish colonization had limited initial impact due to their remote location, while the American period brought greater integration efforts and issues related to land rights.

- The Mandaya people resisted external pressures through various means, adapting while preserving their core cultural identity and Mandaya language.

- Contemporary challenges include securing land rights, cultural preservation, and economic development, but they are actively working to address these issues and advocate for indigenous rights.

- The Mandaya have contributed significantly to Philippine history and culture through their oral traditions, artistic heritage (weaving), resilience, and traditional ecological knowledge.

Conclusion:

The story of the Mandaya Tribe of the Philippines is a compelling chapter in the rich and complex history of the archipelago. From their ancient roots in Eastern Mindanao, their vibrant traditional culture shaped by animism and led by datus, to their encounters with Spanish colonization and the American period, the Mandaya people have demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability.

Their deep connection to their ancestral domain, their efforts in cultural preservation, and their ongoing struggle for land rights and indigenous rights highlight the enduring challenges faced by indigenous groups in the Philippines. Yet, their story is also one of strength, creativity (evident in their magnificent weaving), and the persistent determination to maintain their identity in a rapidly changing world.

The Mandaya language, their oral traditions, and their unique customs are invaluable components of the Philippines’ cultural diversity. Studying the history of the Mandaya people provides a deeper understanding not only of Mindanao history but also of the broader experiences of indigenous groups throughout the archipelago, reminding us of the importance of recognizing, respecting, and supporting the rights and aspirations of all the diverse peoples that make up the Filipino nation. Their legacy is a testament to the strength of tradition and the power of a people united by their history and their inherent right to their land and their way of life.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

Q1: Where do the Mandaya people primarily live in the Philippines? A1: The Mandaya people primarily inhabit the provinces of Davao Oriental and Davao de Oro in the southeastern part of Mindanao, specifically within the Eastern Mindanao region.

Q2: What is the significance of the name “Mandaya”? A2: The name “Mandaya” is believed to come from “man” (person) and “daya” (upstream or upriver), meaning “people living upstream” or “people of the interior,” reflecting their historical settlement in mountainous and inland areas.

Q3: What was the traditional social structure of the Mandaya? A3: Traditional Mandaya society was largely based on kinship groups and communities led by datus, influential leaders who guided their respective groups. The bagani or warrior-chief also held significance.

Q4: What are some key aspects of Mandaya traditional culture? A4: Key aspects include their animism (belief in spirits in nature), intricate weaving of dagmay textiles, oral traditions (epics and folktales), traditional attire, music, and dance.

Q5: How did Spanish colonization affect the Mandaya? A5: The impact of Spanish colonization was initially limited due to the Mandaya’s remote location. Spanish presence was primarily coastal, with limited success in missionary efforts in Mandaya territories.

Q6: What were the effects of the American period on the Mandaya? A6: The American period brought greater contact, attempts at integration through education and infrastructure, and the introduction of new administrative structures and concepts of land ownership, which sometimes led to issues over land rights.

Q7: What are some major challenges facing the Mandaya today? A7: Contemporary challenges include securing land rights against encroachment, cultural preservation amidst modernization, economic development, and ensuring political representation and indigenous rights.

Q8: What does it mean that the Mandaya are part of the Lumad? A8: Lumad is a collective term used since the 1980s to refer to the non-Islamized indigenous groups of Mindanao. Being part of the Lumad signifies their status as one of the numerous distinct indigenous peoples on the island.

Q9: Are there ongoing efforts for cultural preservation among the Mandaya? A9: Yes, there are ongoing efforts by Mandaya elders, cultural workers, and organizations to revitalize the traditional culture, document the Mandaya language and oral traditions, and promote cultural education among younger generations.

Sources:

- Cole, Fay-Cooper. The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao. Field Museum of Natural History, 1913. (A foundational early anthropological study).

- Jocano, F. Landa. Filipino Prehistory: Notes on Chronology and Cultural Unconformities. Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, University of the Philippines System, 1975. (Provides broader context on Philippine indigenous groups).

- Lopez-Gonzaga, Violeta B. The Socio-Political Development of the Indigenous Peoples of Southern Mindanao. Mindanao Studies Consortium, 1991. (Discusses the historical experiences of indigenous groups in the region).

- Rodil, B. R. The Lumad and Moro of Mindanao. Minority Rights Group International, 1994. (Focuses on the rights and history of indigenous peoples in Mindanao).

- Oxfam Philippines. “Mindanao’s Lumad: Caught in the Crossfire.” (Reports on contemporary issues facing Lumad communities, including the Mandaya). https://www.google.com/search?q=https://www.oxfam.org/en/philippines/mindanaos-lumad-caught-crossfire (Provides insight into current indigenous rights issues).

- National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) Philippines. (Official government body related to indigenous peoples’ affairs, provides information on ancestral domain and land rights). https://ncip.gov.ph/

- Academic databases and journals focusing on Philippine history, anthropology, and ethnography (e.g., Philippine Studies, Asian Studies, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies) for more specific scholarly articles on the Mandaya.

(Note: Specific book page numbers or direct links to paywalled academic articles are not feasible within this format, but the provided sources are reputable starting points for further research.)