The history of the Spanish Colonial Period Philippines, spanning over three centuries from the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521 to the end of Spanish rule in 1898, is intrinsically linked to the exploitation of Philippines natural resources by the Spanish Colonizers. Driven by mercantilist ambitions, the Spanish Crown sought to extract wealth from its vast empire, and the Philippine archipelago, despite not possessing the vast silver deposits of its Latin American colonies, offered a different kind of riches: strategic location, fertile lands, valuable timber, potential mineral wealth, and a population to provide indigenous labor. This systematic extraction profoundly reshaped the Philippine Economy, societies, and environment, leaving a complex and often challenging legacy that resonates even today.

From the initial conquest led by figures like Miguel López de Legazpi, the Spanish implemented various systems designed to control land, labor, and trade, all aimed at channeling resources back to Spain or utilizing them to fund the colonial administration and the proselytizing efforts of the Catholic Church. This article will delve into the primary mechanisms employed for resource exploitation, examine the specific resources targeted, analyze the economic policies and institutions established, and discuss the multifaceted consequences for the archipelago and its people during the Spanish Colonial Period Philippines. Understanding this era of resource extraction is crucial for comprehending the historical trajectory of the nation.

The Context of Spanish Arrival and Early Resource Acquisition

The archipelago that would become the Philippines was, prior to Spanish arrival, composed of diverse chiefdoms and settlements with varied economies, engaged in agriculture, fishing, forestry, and vibrant regional trade networks, including connections with China, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Resources were managed primarily for local subsistence and regional exchange.

Initial Contact and Magellan’s Arrival

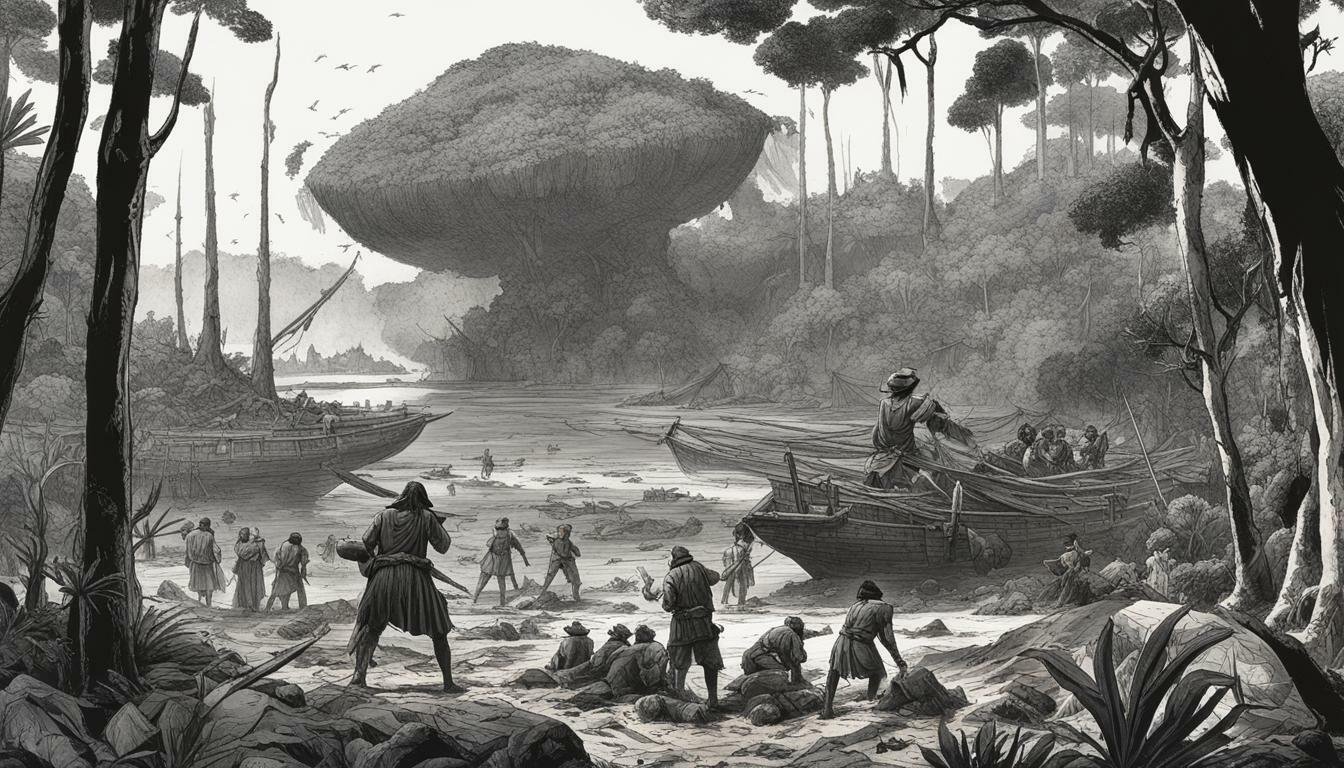

Ferdinand Magellan’s arrival in 1521, though ultimately fatal for him, marked the initial intrusion of a European power with imperial ambitions. While his expedition was primarily focused on finding a westward route to the Spice Islands, his brief interactions provided the Spanish with a glimpse of the archipelago’s potential, including existing gold ornaments and agricultural productivity.

Legazpi and the Establishment of Permanent Settlements

The successful expedition led by Miguel López de Legazpi, beginning in 1565, marked the true start of sustained Spanish colonization. After establishing the first permanent Spanish settlement in Cebu, and later moving to Panay and then Manila (founded in 1571), the Spanish faced the challenge of maintaining their presence and funding the colonial endeavor. This necessitated immediate steps to secure food supplies, building materials, and sources of revenue, initiating the direct exploitation of Philippines natural resources.

Early Forms of Extraction: Tribute and Gold

One of the first methods of resource acquisition was the imposition of tribute (tributo) on conquered native populations. This often involved demanding payments in kind, including rice, cotton, gold, forest products, and other local resources. This system, while ostensibly a recognition of Spanish sovereignty, served as an early form of extracting wealth directly from the labor and resources of the indigenous communities. Gold, present in various forms across the archipelago, was particularly coveted. Early accounts mention the collection of gold as tribute and Spanish efforts to locate sources, although large-scale, sustained gold mining under Spanish direct control proved challenging compared to the Americas.

Key Mechanisms of Resource Exploitation

To facilitate systematic resource control and extraction, the Spanish Colonizers introduced and adapted various colonial institutions and economic policies. These systems were designed to organize indigenous labor, control land, and manage the flow of goods for the benefit of the Spanish Crown and its representatives.

The Encomienda System: Land and Labor Control

Perhaps one of the most significant early mechanisms was the Encomienda System. Introduced in the early years of colonization, an encomienda was a grant of jurisdiction over a specific territory and its inhabitants to a Spanish individual, known as an encomendero. While theoretically the encomendero was responsible for protecting the natives and instructing them in Christianity, the system primarily served as a means to collect tribute and mobilize indigenous labor.

- Mechanism: Encomenderos were granted the right to demand tribute and labor services from the people within their encomienda.

- Impact: This system often led to severe abuses, over-extraction of tribute, and forced labor, causing hardship and depopulation in many areas. It was a direct way for Spaniards to benefit from the land and the people’s productivity.

- Resource Link: The tribute collected included agricultural products, forest goods, and sometimes labor used for public works or personal gain, all derived from the natural resources of the encomienda’s land base.

The Encomienda System was eventually phased out or reformed due to widespread abuse and indigenous resistance, giving way to more centralized forms of administration and taxation, but its legacy of coerced labor and resource extraction lingered.

Polo y Servicio: Forced Labor and Resource Extraction

Another pillar of Spanish exploitation was the Polo y Servicio, a system of forced labor levied upon Filipino males aged 16 to 60 for a specific period each year (originally 40 days, later reduced to 15 days). This labor was utilized for various colonial projects:

- Building ships for the Manila Galleon trade.

- Constructing roads, bridges, and public buildings (churches, forts).

- Working in mines or logging timber.

- Serving in military expeditions.

Polo y Servicio was a direct means of harnessing indigenous labor for projects crucial to the maintenance and economic activities of the colony, many of which were directly tied to resource extraction or facilitating resource trade (like shipbuilding using local timber). The requirement to serve often took men away from their farms and families, disrupting local agriculture and causing significant social and economic strain. The system was frequently abused, with unfair assignments, inadequate pay (if any), and harsh conditions.

The Galleon Trade: Silver for Asian Goods (Impact on Local Production)

While not direct extraction of physical resources from the Philippines for shipment to Spain (the primary cargo from Manila was Chinese silk, porcelain, and other Asian luxury goods, and the return cargo was Mexican silver), the Galleon Trade, specifically the Manila Galleon route between Manila and Acapulco, Mexico, was a major driver of the Colonial Economy and indirectly fueled resource exploitation.

- Mechanism: The trade facilitated the exchange of silver from the Americas for high-value Asian goods. Manila served as the crucial entrepôt.

- Impact on Resources: The need to support the trade required significant local resources:

- Timber: Massive amounts of high-quality timber from Philippine forests were needed to build and repair the galleons in shipyards like those in Cavite. This led to extensive logging.

- Food Supplies: The population concentrated around Manila and the workers involved in shipbuilding and trade needed to be fed, increasing demand on local agricultural production and sometimes leading to forced procurement.

- Labor: Polo y Servicio was heavily utilized for shipbuilding and port activities related to the Galleon Trade.

- Limited Diversification: The focus on the profitable Manila Galleon trade often discouraged investment in developing local industries or diversifying the Philippine Economy beyond providing raw materials and labor for this specific route. The Spanish Crown preferred this lucrative trade over promoting local production that might compete with Spanish goods.

The Galleon Trade made a few individuals wealthy but did little to stimulate broad economic development or improve the lives of the majority of Filipinos. It was an external trade focused on connecting Spanish America with Asia, with the Philippines serving primarily as a conduit and source of support resources.

Monopoly Systems (Tobacco, Abaca, etc.)

In later centuries, particularly in the 18th century, the Spanish Crown established state monopolies over key cash crops to increase revenue directly. The most famous of these was the Tobacco Monopoly, implemented in 1782 by Governor-General José Basco y Vargas.

- Mechanism: Specific provinces (primarily in Northern Luzon like Ilocos, Cagayan, and Nueva Ecija) were designated as tobacco-growing regions. Farmers were required to sell their entire harvest to the government at fixed, often low, prices. The government controlled production, drying, and sale.

- Impact: The monopoly generated significant income for the colonial government and even sent surpluses to Spain. However, it also caused immense hardship for farmers, who were strictly controlled, often received delayed or insufficient payment, and were forbidden from growing other crops or selling tobacco privately. This forced specialization was a direct exploitation of agricultural land and labor for state profit.

- Other Monopolies: Similar, though less extensive, monopolies or state controls were sometimes applied to other products like abaca (hemp), which became increasingly important for cordage.

These monopolies represent a shift towards more direct state control and exploitation of specific agricultural resources for maximum colonial revenue.

Specific Resources Exploited

The exploitation of Philippines natural resources targeted a range of valuable commodities present in the archipelago.

Agricultural Lands and Produce

Agriculture was the backbone of the Philippine economy before and during the Spanish period. The Spanish did not introduce many new crops comparable to the Columbian Exchange in the Americas, but they intensified the production of existing crops and introduced new systems of land ownership and labor to control agricultural output.

- Rice: The staple crop, rice, was demanded as tribute and used to feed the colonial population and those engaged in public works. Spanish control mechanisms like the Encomienda System and later the Hacienda System impacted traditional rice farming.

- Sugar: While sugar production existed pre-colonization, it expanded under Spanish rule, particularly with the growth of large estates (haciendas) worked by tenant farmers or hired labor. Sugar became an increasingly important export, especially in the 19th century.

- Tobacco: As discussed, the Tobacco Monopoly made tobacco one of the most intensely exploited agricultural resources, transforming landscapes and labor patterns in the designated regions.

- Abaca: The demand for rope for ships, including the Manila Galleon and later international trade, increased the exploitation of abaca fiber, particularly in regions like Bicol.

The systems of Land Ownership evolved under Spanish rule. While traditional communal or family ownership existed, the Spanish introduced concepts of private ownership, grants to Spaniards (like the Encomienda System, which evolved into private estates), and crucially, the accumulation of vast tracts of land by religious orders, known as Friar Lands. These large landholdings, often managed as haciendas, concentrated control over agricultural resources and labor in the hands of a few, displacing indigenous populations and creating a system of tenancy that often left farmers in precarious positions.

Mineral Wealth

Pre-colonial Philippines had existing small-scale mining of gold, copper, and iron. The Spanish were keen to find significant gold or silver deposits, hoping for wealth comparable to Mexico or Peru.

- Gold: While gold was present and collected as tribute, large, easily accessible deposits suitable for extensive Spanish-style mining operations were not found. Attempts at systematic gold mining occurred in areas like Paracale (Camarines Norte) and the Cordillera, but challenges related to technology, labor, resistance from indigenous miners (like the Igorot), and geological factors limited the scale compared to other Spanish colonies.

- Other Minerals: There was some extraction of iron and copper for local use and shipbuilding, but large-scale mining was not a defining feature of Spanish exploitation in the Philippines compared to agriculture or timber.

Despite the hopes, mineral wealth did not become the primary source of colonial revenue, unlike in parts of the Americas.

Timber and Forest Products

Philippine forests were a rich source of high-quality hardwoods, essential for shipbuilding, construction, and furniture.

- Shipbuilding: The demand for ships for the Galleon Trade, military use, and inter-island transport led to significant forestry exploitation. Entire mountainsides were sometimes denuded to acquire timber. This was a primary use of forced labor (Polo y Servicio).

- Construction: Timber was also vital for building churches, forts, government buildings, and Spanish homes.

- Other Products: Forest products like rattan, beeswax, and resins were also collected, sometimes as tribute or for trade.

Uncontrolled logging for colonial needs had significant environmental impacts, including deforestation and soil erosion in affected areas.

Marine and Other Resources

Fishing was and remained a vital source of food. While the Spanish did not implement large-scale industrial fishing operations, coastal communities’ resources were often impacted by colonial demands, population shifts, and sometimes by providing labor for galleon-related activities. Other resources like pearls (historically important in areas like Sulu) were also subject to collection and trade.

Economic Policies and Institutions of Spanish Rule

The exploitation of Philippines natural resources was shaped and driven by the overarching economic philosophy and institutions imposed by the Spanish Crown.

Mercantilism and the Spanish Crown’s Objectives

Spanish colonial economic policy was guided by mercantilism, the prevailing economic theory in Europe at the time. Mercantilism held that a nation’s wealth was measured by its accumulation of precious metals (gold and silver). Colonies were seen as existing primarily for the benefit of the mother country, serving as sources of raw materials and markets for manufactured goods.

- Extraction Focus: This philosophy directly encouraged the exploitation of colonial resources that could either be converted into precious metals (like silver from the Americas, though less so in the Philippines) or traded for goods that could be sold for silver (like Asian goods via the Galleon Trade).

- Trade Restrictions: The Spanish Crown imposed strict controls on colonial trade, aiming to channel all wealth through Spain and prevent direct trade with foreign powers. The Manila Galleon was a prime example of a highly controlled and restricted trade route designed to serve Spanish interests.

The Royal Company of the Philippines

In an attempt to stimulate direct trade between Spain and the Philippines, and to reduce reliance on the Mexico-based Galleon Trade, the Royal Company of the Philippines was established in 1785.

- Goal: To promote direct trade via the Cape of Good Hope, importing Spanish goods into the Philippines and exporting Philippine products (indigo, sugar, tobacco, abaca, etc.) directly to Spain and other parts of Europe.

- Impact: The company had limited success due to various factors, including resistance from interests involved in the Galleon Trade, inefficiency, and difficulties competing with established trade networks. While it did encourage the production of certain cash crops for export, its overall impact on transforming the fundamental nature of resource exploitation or significantly diversifying the Philippine Economy was constrained. It represented a later effort by the Spanish Crown to gain more direct economic benefit from the colony’s resources.

Impact of Friar Lands and the Hacienda System

As mentioned, the accumulation of vast landholdings by religious orders (Augustinians, Dominicans, Franciscans, Recollects) constituted the Friar Lands. These lands, often acquired through donations, purchases, or questionable means, became large agricultural estates managed as haciendas.

- Control over Resources: The Friar Lands and other large haciendas concentrated control over prime agricultural land and water resources in the hands of a few entities or individuals.

- Labor Relations: These estates were worked by tenants (kasama) or hired laborers, often under arrangements that were economically disadvantageous to them, contributing to rural poverty and dependence. The system represented an entrenched form of Land Ownership that facilitated the exploitation of agricultural resources and the labor tied to them.

- Social Impact: The issue of Friar Lands became a major source of discontent and a key grievance that fueled the Independence Movement in the late 19th century, highlighting how land and resource control were central to colonial power and exploitation.

Taxation and its Burden

Beyond tribute and labor, various forms of taxation were imposed on the population, further extracting wealth derived from their labor and resources. These included head taxes (cedulapersonal introduced later), taxes on goods, and customs duties on trade. While necessary for running the colonial administration, the burden of taxation often fell disproportionately on the lower classes and indigenous populations, compelling them to produce more from their lands and labor to meet these obligations, thus driving further exploitation.

Consequences and Impacts of Exploitation

The systematic exploitation of Philippines natural resources by the Spanish Colonizers had profound and lasting consequences across various aspects of the archipelago’s existence.

On Indigenous Populations and Societies

The impact on the indigenous populations was arguably the most severe.

- Forced Labor and Displacement: Systems like the Encomienda System and Polo y Servicio disrupted traditional life, forced people into arduous and often dangerous labor far from their homes, and led to suffering, illness, and even death. Displacement occurred as land was alienated for encomiendas, haciendas, and later, Friar Lands.

- Economic Disruption: Traditional economic activities and regional trade networks were often undermined or reoriented to serve colonial interests (e.g., the focus on the Manila Galleon trade drew resources and labor away from other potential developments).

- Social Hierarchy: The colonial system created a new social hierarchy based on race and class, with Spaniards at the top benefiting most from resource exploitation, while indigenous Filipinos were largely relegated to providing labor and resources.

- Cultural Changes: While the Catholic Church‘s influence led to widespread conversion, the imposition of colonial rule and economic systems also impacted traditional governance structures, social customs, and relationship with the environment.

On the Environment

The intensive focus on extracting specific resources led to significant environmental changes.

- Deforestation: The demand for timber for shipbuilding (particularly for the Manila Galleon) and construction led to the clearing of vast tracts of old-growth forests, especially in coastal and accessible areas. This had cascading effects on ecosystems, soil stability, and biodiversity.

- Land Degradation: Intensive agricultural practices, sometimes without sustainable methods, and the pressure to produce more from limited land, could contribute to soil depletion and erosion.

- Impact of Mining: Although less extensive than in the Americas, local mining activities could cause localized environmental damage.

On the Development of the Philippine Economy

The Colonial Economy was structured primarily to benefit the Spanish Crown and Spanish elites, not to foster independent, diversified economic development in the Philippines.

- Dependency: The economy became largely dependent on providing raw materials and serving as an entrepôt for the Galleon Trade. This created a dependency on external markets and colonial policies rather than building a self-sustaining internal economy.

- Lack of Industrialization: There was little investment in developing local industries beyond basic crafts and raw material processing. The Spanish preferred to import manufactured goods, hindering local industrial growth.

- Unequal Distribution of Wealth: The wealth generated from resource exploitation was concentrated in the hands of the Spanish colonial government, religious orders, and a small number of Spanish and later, mestizo elites who benefited from the Encomienda System, haciendas, and trade. The majority of the Filipino population remained impoverished.

Seeds of Resistance and Nationalism

The burdens imposed by resource exploitation – forced labor, excessive tribute and taxation, land alienation, and the restrictive economic policies – were major sources of discontent and rebellion throughout the Spanish Colonial Period Philippines.

- Early Revolts: Numerous local and regional revolts, such as those led by Maniago (1660) and Malong (1661) protesting against Polo y Servicio and tribute, or the Silang revolt (1762-1763) partly against the Tobacco Monopoly, demonstrated the deep resentment caused by colonial exploitation.

- Growing Nationalism: Over centuries, the shared experience of being subjected to foreign rule, economic exploitation, and social injustice contributed to the development of a sense of common identity and grievances, eventually culminating in the rise of the Independence Movement in the late 19th century. Issues like the Friar Lands and economic inequality were central to the platform of the revolutionaries.

Comparison and Transition

Understanding Spanish exploitation can be illuminated by briefly comparing it to pre-colonial practices and the subsequent colonial period.

Spanish vs. Pre-colonial Resource Management

Pre-colonial societies had diverse systems of resource management, generally focused on subsistence, local needs, and regional trade. While hierarchies and tribute systems existed, they were typically on a smaller scale and integrated within local social structures. Spanish rule imposed a centralized, large-scale system driven by external, mercantilist goals, fundamentally altering the relationship between the people and their land and resources.

Spanish vs. American Colonial Period Exploitation

Following the Spanish-American War and the Treaty of Paris (1898), the American Colonial Period began. While the Americans also engaged in resource extraction and control, their methods and scale differed. American rule saw increased focus on large-scale export agriculture (sugar, coconut, abaca), mining, and forestry, often facilitated by American companies and new legislation regarding land ownership and resources. While infrastructure developed, the focus remained on integrating the Philippine economy into the American market and providing resources for U.S. industry, representing a continuation, albeit with different mechanisms and intensity, of colonial exploitation.

Historical Interpretations and Debates

Historians continue to analyze and debate the nature and extent of Spanish exploitation in the Philippines. While there is broad agreement on the reality of forced labor, tribute, and economic policies designed for colonial benefit, the nuances are debated:

- The degree to which the Philippines was a profitable colony for Spain compared to its American possessions.

- The specific impact of institutions like the Royal Company of the Philippines.

- The extent to which Spanish rule inadvertently laid some groundwork for future economic development (e.g., infrastructure for trade).

- The agency and resilience of indigenous populations in resisting or adapting to the systems of exploitation.

Different perspectives exist, drawing on various primary and secondary sources, highlighting the ongoing process of understanding this complex historical period.

Conclusion

The exploitation of Philippines natural resources by the Spanish Colonizers was a defining characteristic of the Spanish Colonial Period Philippines. Through systems like the Encomienda System, Polo y Servicio, the restrictions imposed by the Manila Galleon trade, and state monopolies like the Tobacco Monopoly, the Spanish Crown and its representatives systematically extracted wealth, labor, and valuable commodities from the archipelago.

Key resources targeted included fertile agricultural lands, timber for shipbuilding and construction (Forestry), and to a lesser extent, mineral deposits (Mining). The establishment of large Friar Lands and the Hacienda System fundamentally altered patterns of Land Ownership and created enduring social and economic inequalities.

Driven by mercantilist Economic Policies and enforced by colonial institutions, this systematic extraction had devastating consequences for indigenous labor and societies, leading to displacement, hardship, and the disruption of traditional economies. It also inflicted significant environmental damage, particularly through deforestation. Furthermore, the focus on servicing the needs of the colonial power and external trade routes like the Galleon Trade hindered the diversified development of the Philippine Economy, fostering dependency.

Ultimately, the experience of exploitation fueled widespread discontent and became a crucial factor in the rise of Resistance movements and the eventual Independence Movement, as Filipinos sought to reclaim control over their land, labor, and destiny from the Spanish Colonizers. Understanding this history is essential for grasping the roots of many socio-economic challenges and the long struggle for self-determination in the Philippines.

Key Takeaways:

- Spanish colonization in the Philippines was heavily focused on the systematic exploitation of Philippines natural resources.

- Key mechanisms included the Encomienda System, Polo y Servicio (forced indigenous labor), and state Monopoly Systems (especially Tobacco Monopoly).

- The Galleon Trade (specifically the Manila Galleon) indirectly drove resource exploitation, particularly Forestry for shipbuilding.

- Spanish Economic Policies, guided by mercantilism, prioritized extracting wealth for the Spanish Crown.

- The establishment of Friar Lands and the Hacienda System concentrated Land Ownership and control over agricultural resources.

- The consequences included severe hardship for indigenous populations, environmental damage, hindered economic development, and fueled Resistance and the Independence Movement.

- Figures like Ferdinand Magellan and Miguel López de Legazpi represent the initial phase of this colonial enterprise.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

Q1: What were the primary goals of the Spanish Colonizers in exploiting Philippine resources? A1: The primary goals were aligned with mercantilism: to generate wealth for the Spanish Crown through tribute, taxes, control of trade (like the Manila Galleon), and direct exploitation of valuable resources like timber and agricultural products (especially via monopolies like the Tobacco Monopoly). Funding the colonial administration and the missions of the Catholic Church were also key objectives that required resource extraction.

Q2: How did the Encomienda System facilitate resource exploitation? A2: The Encomienda System granted Spanish individuals control over specific territories and their indigenous inhabitants. This allowed encomenderos to demand tribute in the form of goods (agricultural produce, gold, forest products) and indigenous labor for their personal benefit and in service of the colonial state, directly leveraging the resources of the land and the people on it.

Q3: What was the significance of the Tobacco Monopoly in the context of resource exploitation? A3: The Tobacco Monopoly (1782-1882) was significant because it represented a direct and highly controlled state exploitation of a specific agricultural resource. It forced farmers in designated areas to grow only tobacco and sell it to the government at fixed prices, generating substantial revenue for the colonial state but causing significant hardship and economic control over the lives and lands of the affected Filipino farmers.

Q4: How did the Galleon Trade impact resource use in the Philippines, even though it primarily traded Asian goods for silver? A4: The Galleon Trade required massive logistical support from the Philippines. This included extensive forestry for building the large Manila Galleon ships using forced indigenous labor (Polo y Servicio), and the need to supply food and other resources for the population concentrated around Manila and the shipyards. The focus on the trade also diverted resources and attention away from developing other sectors of the Philippine Economy.

Q5: What were the long-term consequences of Spanish exploitation of natural resources in the Philippines? A5: The long-term consequences included persistent rural poverty and inequality due to skewed Land Ownership patterns (like Friar Lands and the Hacienda System), environmental degradation (especially deforestation), an economy that remained largely focused on exporting raw materials, and a legacy of social and economic disparity. It also sowed the seeds of discontent that fueled the Resistance movement and the struggle for independence.

Sources:

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. History of the Filipino People. 8th ed. C & E Publishing, 1990. (A widely used textbook providing a comprehensive overview of Philippine history, including the Spanish colonial period and its economic aspects).

- Constantino, Renato. The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Tala Publishing Services, 1975. (Offers a nationalist perspective on Philippine history, critically analyzing the impact of colonial rule and resource exploitation).

- Cushner, Nicholas P. Spain in the Philippines: From Conquest to Revolution. IPC Monographs, No. 1. Ateneo de Manila University, 1971. (Provides an academic account of the Spanish colonial administration and economic policies).

- De la Costa, Horacio. The Jesuits in the Philippines, 1581-1768. Harvard University Press, 1961. (While focused on the Jesuits, it provides valuable context on the role of religious orders, landholding, and economic activities).

- Larkin, John A. Sugar and the Origins of Modern Philippine Society. University of California Press, 1993. (Focuses on the development of the sugar industry, providing insights into agricultural exploitation and the Hacienda System).

- Phelan, John Leddy. The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700. University of Wisconsin Press, 1967. (Examines the early period of Spanish colonization, including the implementation of the Encomienda System and early economic interactions).

- Schurz, William Lytle. The Manila Galleon. E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939. (A classic work detailing the mechanics and significance of the Manila Galleon trade).

- Owen, Norman G. Prosperity Without Progress: Manila Hemp and Material Life in the Colonial Philippines. Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1984. (Explores the exploitation of abaca and its economic and social impact).

- Roth, Dennis Morrow. The Friar Estates of the Philippines. University of New Mexico Press, 1977. (Detailed study on the historical development and impact of Friar Lands).

(Note: While primary sources like colonial decrees, official reports, and chronicles exist, accessing and citing specific primary documents extensively within this format is challenging. The listed secondary sources by reputable historians synthesize and analyze primary source information).