I. Introduction

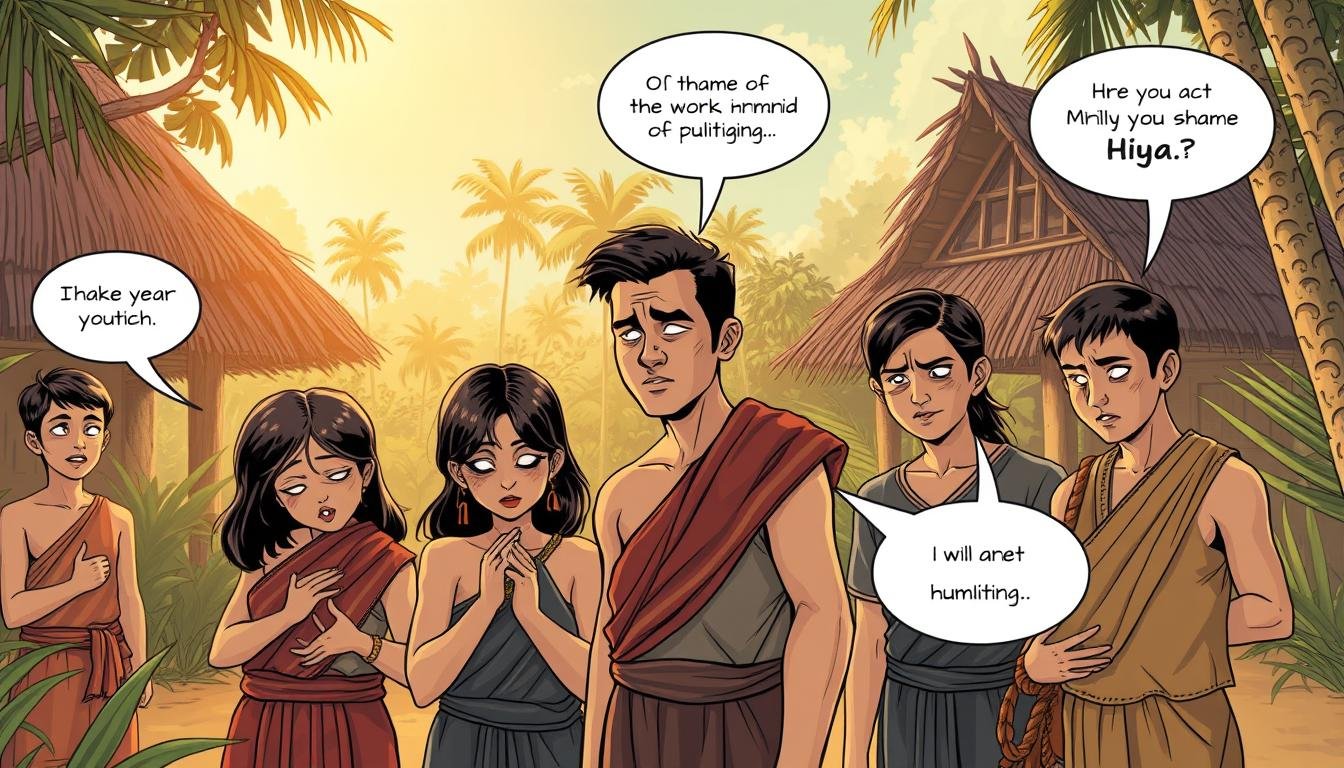

Ever hesitated to ask for help, fearing you might impose? Or felt a deep flush when put on the spot, even if you hadn’t done anything wrong? This might be a glimpse into the complex, often misunderstood Filipino concept of hiya. It’s a feeling deeply woven into the fabric of Filipino culture, frequently observed yet challenging to define accurately for outsiders and even for Filipinos themselves.

While often translated simplistically as ‘shame,’ ’embarrassment,’ or ‘shyness,’ Filipino Hiya carries a weight and nuance far beyond these single words. It’s a core element influencing social interactions, personal decisions, and the very way Filipinos perceive themselves and relate to others within their community. Understanding hiya is crucial not just for appreciating Filipino culture but for fostering meaningful connections and navigating interactions effectively.

The purpose of this piece is to delve beyond simple translations and foster a nuanced understanding of hiya. We aim to explore its intricate definition, uncover its deep cultural roots, examine how it manifests in everyday life and behavior, discuss its multifaceted nature – both its positive contributions and potential drawbacks – and consider its relevance in the modern, globalized world. This journey will unpack why Filipino Shame, as a translation, falls short and reveal the deeper significance of hiya within the Filipino experience. Join us as we first attempt to define hiya more accurately, differentiate it from Western notions of shame, explore its cultural underpinnings tied to core Filipino values, observe its manifestations, analyze its dual nature, and reflect on its place today.

II. Defining Hiya: Beyond Simple Translation

One of the primary hurdles in understanding Filipino Hiya is the sheer challenge of translation. English words like “shame,” “embarrassment,” “timidity,” or “shyness” only capture fragments of its meaning. Each falls short because hiya isn’t just an internal feeling; it’s profoundly relational and situational. Attributing it solely to personal inadequacy misses its deep connection to social expectations and the preservation of harmony. Relying on these translations can lead to misinterpretations of Filipino behavior and motivations. For instance, hesitation might be seen as weakness rather than a manifestation of hiya aimed at maintaining politeness or avoiding imposition.

To grasp hiya more fully, we must consider its core components:

- Sense of social propriety and appropriateness: At its heart, hiya involves an acute awareness of what is considered proper or improper within a given social context. It guides individuals on how to behave respectfully according to unspoken rules and expectations. This sense of social propriety is fundamental to navigating Filipino social landscapes.

- Sensitivity to social norms and the judgment of others: Individuals experiencing hiya are highly attuned to how others might perceive their actions. There’s a strong concern about potentially violating social norms and facing disapproval or negative judgment from the community or group. This sensitivity reinforces adherence to collective standards.

- Awareness of one’s place within a social hierarchy or group: Hiya often involves recognizing one’s position relative to others – whether based on age, status, or relationship (e.g., guest vs. host, younger vs. elder, employee vs. employer). This awareness dictates appropriate levels of deference, directness, or assertiveness.

- Feeling of inadequacy or potential loss of face (mukha): A critical element is the fear of mapahiya – to be put to shame or to cause someone else shame, leading to a loss of face (mukha). Mukha, often translated as ‘face,’ represents one’s social standing, dignity, and self-esteem as perceived by the community. Protecting one’s mukha and the mukha of others is paramount, and hiya serves as a powerful internal regulator in this regard. The potential for public embarrassment or diminishing one’s social worth fuels the feeling of hiya.

It’s also vital to distinguish Filipino Hiya from Western concepts like “shame” or “guilt”:

- External vs. Internal Focus: While Western guilt often stems from an internal sense of moral transgression (“I did something bad”), and shame from a negative evaluation of the self (“I am bad”), hiya is predominantly focused on external social judgment and the potential disruption of social harmony. The primary concern is often “What will others think?” or “How will this affect my relationship with the group?” rather than an internal moral compass alone.

- Social Harmony vs. Individual Failing: Hiya operates strongly within the context of maintaining smooth interpersonal relations (pakikisama). Actions are often moderated by hiya to prevent causing offense, discomfort, or conflict within the group. Western shame might focus more on individual failure or inadequacy relative to personal standards, whereas hiya is intrinsically linked to the well-being and perception of the collective. Understanding this distinction is key to appreciating the motivations behind certain Filipino behaviors.

III. The Cultural Tapestry: Roots and Significance of Hiya

Filipino Hiya doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it’s deeply interwoven with the rich tapestry of core Filipino values and the predominantly collectivist culture of the Philippines. Understanding these connections illuminates why hiya holds such significance.

- Connection to Core Filipino Values:

- Kapwa (Shared Identity/Self): Perhaps the most foundational Filipino psychological concept, kapwa refers to a sense of shared identity, seeing the self in the other, or “shared inner self.” It implies that the ‘self’ is not an isolated individual but exists in relation to others. Hiya arises from this relational understanding. An action that brings shame doesn’t just affect the individual; it reflects on the family, the group, the kapwa. Conversely, one feels hiya for others, anticipating their potential discomfort or embarrassment, demonstrating the interconnectedness inherent in kapwa. This value fosters empathy and consideration, which are intertwined with the experience of hiya.

- Pakikisama (Smooth Interpersonal Relations): This value emphasizes getting along with others, maintaining group harmony, and avoiding conflict. Hiya acts as a crucial social lubricant facilitating pakikisama. By making individuals hesitant to be overly assertive, confrontational, or demanding, hiya helps preserve smooth interpersonal relations. It encourages agreeableness and prioritizes group cohesion over individual desires that might cause friction. The fear of disrupting pakikisama is a potent trigger for hiya.

- Pakikiramdam (Sensitivity/Feeling Others Out): This refers to a heightened sensitivity and ability to read subtle cues, unspoken messages, and the emotional states of others. Hiya is closely linked to pakikiramdam. It requires being attuned to the social atmosphere, anticipating potential disapproval, and adjusting one’s behavior accordingly. A person exercising pakikiramdam might feel hiya and thus refrain from asking a question if they sense it might inconvenience someone or reveal their own ignorance, thereby preserving social ease.

- Utang na Loob (Debt of Gratitude): This signifies a deep sense of obligation to repay favors or kindness received. Hiya can interact significantly with utang na loob. One might feel hiya to refuse a request from someone to whom they owe utang na loob, even if it’s inconvenient. Conversely, someone might feel hiya to ask for help, especially from someone they already feel indebted to, fearing it might deepen the obligation or appear presumptuous. This interplay adds another layer to the complexity of hiya in social exchanges.

- Role in Social Structure and Harmony:

- Reinforcing Respect: Hiya plays a role in maintaining social hierarchies by encouraging deference and respect towards elders, authority figures, and those of higher status. Younger individuals might feel hiya expressing strong opinions or contradicting elders directly.

- Maintaining Face (Mukha): As discussed earlier, preserving one’s own mukha (social standing, dignity) and that of others is vital. Hiya serves as a constant reminder to act in ways that uphold mukha, preventing actions that could lead to pagkapahiya (being shamed) for anyone involved.

- Discouraging Disruptive Behavior: By making individuals sensitive to social judgment, hiya discourages actions that might be seen as boastful, arrogant, overly aggressive, or generally disruptive to the peace and harmony of the group. It promotes conformity to accepted social norms.

- Collectivist Culture Context:

The Philippines is generally considered a collectivist culture, where group goals, interdependence, and social harmony are often prioritized over individual autonomy and achievement. In such a context, hiya functions as a powerful mechanism for social control and cohesion. What affects one person affects the group. Individual actions are constantly evaluated based on their impact on collective well-being and reputation. Therefore, hiya isn’t just a personal feeling but a socio-cultural phenomenon deeply embedded in the need to belong, maintain good relationships, and ensure the smooth functioning of the collective. The emphasis is less on “What do I want?” and more on “How will this affect us?” This collectivist culture backdrop is essential for understanding the pervasive influence of Filipino Hiya.

IV. Manifestations of Hiya in Daily Life and Behavior

Understanding the theoretical and cultural basis of Filipino Hiya is one thing; recognizing its practical manifestations in everyday interactions is another. Hiya subtly and profoundly shapes Filipino communication styles, behaviors, and even major life decisions.

- Communication Styles: Filipino communication styles are often characterized by a degree of indirectness, largely influenced by hiya and the desire for pakikisama.

- Indirectness: Direct refusals (“No”) can be perceived as harsh or confrontational, potentially causing loss of face (mukha) for either party. Hiya often leads Filipinos to use more roundabout ways to decline or disagree. This might involve ambiguous answers (“We’ll see,” “Maybe,” “I’ll try”), changing the subject, or offering gentle excuses rather than a flat negative. This indirect communication requires careful listening and pakikiramdam to understand the true message.

- Hesitancy in Expressing Opinions: Especially in group settings or when interacting with superiors, hiya can make individuals hesitant to voice dissenting opinions, ask critical questions, or even share personal achievements for fear of appearing boastful, disruptive, or ignorant. Saving face – both one’s own and others’ – often takes precedence over direct expression.

- Use of Intermediaries (Tulay): To navigate potentially sensitive situations (like asking for a significant favor, delivering bad news, or resolving a conflict), Filipinos might employ a tulay (bridge) – a trusted intermediary. This person can broach the subject more delicately, minimizing the potential for direct confrontation and the associated hiya for the primary parties involved.

- Behavioral Indicators: Hiya often manifests through non-verbal cues and specific actions:

- Avoiding Eye Contact: While direct eye contact is valued in some cultures, in certain Filipino contexts (especially when speaking to elders, authority figures, or when feeling shy or embarrassed), avoiding sustained eye contact can be a sign of respect or a manifestation of hiya.

- Physical Cues: Blushing, lowering the head, speaking softly, fidgeting, or maintaining a reserved posture can all signal feelings of hiya. These are often involuntary physiological responses to feeling exposed or evaluated.

- Hesitation in Accepting Compliments or Help: Filipinos might deflect compliments (“Oh, it was nothing,” “Anyone could have done it”) or initially refuse offers of help or refreshments, even if wanted. This isn’t necessarily false modesty but can stem from hiya – not wanting to appear needy, boastful, or presumptuous. Persistent, gentle offering is often required.

- Reluctance to Ask Questions: The fear of appearing stupid or ignorant (mapahiya in front of others) can make individuals, especially students or subordinates, hesitant to ask for clarification or admit they don’t understand something. This manifestation of hiya can unfortunately hinder learning or task completion.

- Decision-Making Impact: The influence of hiya extends beyond simple interactions into significant life choices:

- Fear of Failure or Standing Out: Hiya can contribute to a fear of taking risks or pursuing paths that might lead to public failure or negative judgment. The potential loss of face (mukha) associated with failure can be a powerful deterrent. Similarly, standing out too much, even through success, can sometimes trigger hiya if it disrupts group harmony or appears boastful.

- Influence on Choices: Decisions about careers (choosing stable, ‘safe’ paths), personal relationships (hesitancy in expressing feelings or pursuing partners), seeking opportunities (not applying for promotions or scholarships due to fear of inadequacy or rejection), or even seeking medical help can be influenced by hiya. The fear of imposing, being judged, or failing can significantly narrow perceived options.

- Specific Social Scenarios: Hiya is particularly palpable in certain situations:

- Host-Guest Interactions: Guests often display hiya by initially refusing food or drinks (“Nakakahiya naman” – “It’s embarrassing/I feel shy”), while hosts insistently offer hospitality to avoid the hiya of appearing inhospitable.

- Dealing with Authority: Interactions with teachers, bosses, government officials, or elders are often marked by formality and deference rooted in hiya.

- Public Speaking/Performance: Stage fright is universal, but the fear of mapahiya in front of an audience can be particularly intense, amplified by the collective nature of Filipino Hiya.

- Requests and Refusals: Navigating requests (asking for favors) and refusals requires careful maneuvering around potential hiya, often involving indirect language or the use of intermediaries.

Understanding these manifestations is key for effective cross-cultural communication and interpreting Filipino behavior with greater cultural sensitivity.

V. The Double-Edged Sword: Positive and Negative Dimensions of Hiya

Like many deeply ingrained cultural concepts, Filipino Hiya is not inherently ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ It functions as a double-edged sword, offering significant social benefits while also presenting potential drawbacks for individuals and the community. Recognizing both facets is essential for a balanced perspective.

- Positive Aspects: In many ways, hiya serves valuable social functions, contributing positively to the community fabric:

- Promotes Humility and Modesty: Hiya encourages individuals to avoid arrogance or excessive self-promotion, fostering a sense of humility that is often highly valued in Filipino culture.

- Encourages Politeness, Respectfulness, and Good Manners: The sensitivity to others’ feelings and the desire to avoid causing offense, inherent in hiya, naturally lead to polite and respectful behavior, especially towards elders and those in authority. It underpins many social graces.

- Acts as a Social Lubricant: By encouraging deference and discouraging confrontation, hiya helps maintain smooth interpersonal relations (pakikisama). It minimizes friction in daily interactions, acting as a social lubricant that contributes to group harmony.

- Contributes to Social Order and Cohesion: By reinforcing adherence to social norms and respect for hierarchy, hiya helps maintain social order and strengthens community bonds. It implicitly encourages behavior that supports the collective well-being.

- Negative Aspects / Potential Downsides: However, an overabundance or misapplication of hiya can have detrimental effects:

- Can Stifle Self-Expression and Assertiveness: The fear of standing out or causing offense can prevent individuals from expressing their true opinions, creative ideas, or personal needs. This can hinder personal growth and authentic communication.

- May Prevent Individuals from Asking for Needed Help: Hiya can be a significant barrier to seeking necessary support, whether it’s academic help, financial assistance, mental health services, or simply asking a neighbor for a small favor. The fear of imposing or revealing vulnerability can lead to suffering in silence.

- Can Lead to Avoidance of Necessary Conflict Resolution: While hiya promotes harmony, it can also lead to the avoidance of addressing problems or conflicts directly. Issues may fester unresolved because initiating a difficult conversation triggers too much hiya.

- May Contribute to Feelings of Anxiety or Inadequacy (“Inferiority Complex”): Constantly worrying about others’ judgment and feeling hesitant to act can foster anxiety and a persistent feeling of not being good enough. In some cases, it can manifest as what might be perceived as an inferiority complex.

- Can Be a Barrier to Reporting Wrongdoing: The hiya associated with potentially disrupting harmony, challenging authority, or becoming the center of negative attention can prevent individuals from reporting abuse, corruption, or other wrongdoings, thereby protecting the status quo.

- Context is Key: It’s crucial to emphasize that whether hiya is perceived or functions positively or negatively often depends heavily on the specific situation, the individuals involved, and the broader cultural context. What is considered appropriately respectful hesitation in one scenario might be detrimental inaction in another. The degree of hiya considered appropriate can also vary significantly based on factors like age, gender, social status, and regional background. A nuanced understanding avoids generalizations and appreciates the situational nature of Filipino Hiya.

VI. Understanding Hiya in the Modern Context

The Philippines, like all cultures, is not static. Forces like globalization, technological advancement, urbanization, and mass migration inevitably influence traditional values and norms, including Filipino Hiya. Understanding how hiya operates and potentially evolves in the 21st century is crucial.

- Evolution and Generational Shifts: There is ongoing discussion and anecdotal evidence suggesting that perceptions and expressions of hiya might be shifting, particularly among younger, urbanized Filipinos. Factors contributing to this include:

- Increased exposure to Western media and cultural values emphasizing individualism and directness.

- Educational systems that may encourage more active participation and critical thinking.

- Changing family structures and social dynamics.

- Greater anonymity in urban settings compared to close-knit rural communities. Younger generations might exhibit less hiya in certain situations, being more willing to voice opinions, ask questions, or challenge norms compared to their elders. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean hiya is disappearing, but rather that its triggers and manifestations might be evolving. The core sensitivity to social context often remains, even if expressed differently. The tension between traditional expectations of hiya and modern aspirations for self-expression is a real experience for many Filipinos today.

- Impact of Globalization and Diaspora: With millions of Filipinos living and working abroad, the interaction between hiya and other cultural norms becomes particularly significant.

- Navigating Directness: Filipinos in the Filipino diaspora often face challenges in cultures that value direct communication and assertiveness (e.g., North America, parts of Europe). Behaviors rooted in hiya, such as indirect communication or reluctance to self-promote, can be misinterpreted as evasiveness, lack of confidence, or incompetence in workplaces or social settings abroad. This necessitates a conscious effort towards cross-cultural communication adaptation.

- Challenges and Adaptations: Filipinos abroad must often learn to navigate situations requiring more directness, such as negotiating salaries, participating in meetings, or disagreeing openly, which might conflict with ingrained feelings of hiya. This can be a source of stress but also leads to adaptation and the development of bicultural communication strategies. Many learn to code-switch their behavior depending on the cultural context.

- Weakening or Reinterpretation: Constant exposure to different cultural frameworks and distance from the homeland’s immediate social pressures might lead to a gradual weakening or reinterpretation of hiya among some members of the diaspora, particularly in second and third generations. However, for many, it remains a core part of their Filipino identity, shaping their interactions within Filipino communities abroad and influencing how they raise their children.

- Importance of Nuanced Understanding: In our increasingly interconnected world, recognizing the complexity of Filipino Hiya – moving beyond the simplistic label of “Filipino Shame” – is more critical than ever.

- For non-Filipinos interacting with Filipinos (in business, education, healthcare, or personal relationships), understanding hiya fosters empathy, prevents misinterpretations, and facilitates more effective and respectful cross-cultural communication. It allows one to appreciate the motivations behind certain behaviors rather than judging them based on different cultural standards.

- For Filipinos themselves, especially those navigating multiple cultural contexts, understanding the roots and manifestations of their own hiya can be empowering. It allows for conscious reflection on how it influences their behavior and choices, enabling them to navigate different social expectations more effectively.

- Promoting cultural sensitivity requires acknowledging and respecting such deep-seated cultural concepts. Recognizing hiya allows for deeper insights into Filipino psychology and the values that shape the Filipino identity.

VII. Conclusion

Our exploration has revealed that Filipino Hiya is far more intricate than a simple translation like “Filipino Shame” or embarrassment suggests. It is a deeply embedded socio-emotional concept, a cornerstone of Filipino psychology and social interaction. We’ve seen how it’s intrinsically linked to core Filipino values such as Kapwa (shared identity), Pakikisama (smooth interpersonal relations), Pakikiramdam (sensitivity), and Utang na Loob (debt of gratitude), all operating within a predominantly collectivist culture. Hiya manifests in distinct Filipino communication styles (like indirect communication) and specific Filipino behaviors, influencing everything from daily interactions to major life decisions, always with an eye towards maintaining social propriety and avoiding the loss of face (mukha). We’ve also acknowledged its dual nature – acting as a positive social lubricant promoting respect and harmony, while also potentially stifling expression and hindering help-seeking. Furthermore, we recognized that hiya is not static, evolving under the influence of modernization and globalization, presenting unique challenges and adaptations, especially for the Filipino diaspora.

Ultimately, a genuine understanding of hiya requires looking beyond superficial labels. It demands appreciating its complex role in shaping Filipino identity, regulating social dynamics, and reflecting a worldview centered on relational harmony and shared social consciousness. It is not merely about feeling bad; it’s about navigating the intricate web of social relationships with sensitivity and awareness.

Embracing this complexity, rather than simplifying or judging it, is paramount. Recognizing the nuances of Filipino Hiya fosters greater cultural sensitivity, enhances cross-cultural communication, and builds bridges of empathy and understanding. Whether within Filipino communities or in interactions across cultures, appreciating the depth of hiya allows for more meaningful, respectful, and effective connections. It reminds us that understanding culture requires looking deeper, listening closely, and acknowledging the rich, multifaceted ways humans navigate their social worlds.

Key Takeaways:

- Hiya is Complex: It’s more than just ‘shame’; it involves social propriety, sensitivity to judgment, awareness of hierarchy, and fear of losing face (mukha).

- Culturally Rooted: Deeply connected to core Filipino values like Kapwa, Pakikisama, Pakikiramdam, and Utang na Loob, thriving in a collectivist context.

- Influences Behavior: Manifests in indirect communication, behavioral cues (eye contact avoidance, etc.), and can impact significant life decisions.

- Double-Edged: Has positive aspects (promotes humility, respect, social harmony) and negative ones (can stifle expression, prevent help-seeking, avoid conflict resolution).

- Context Matters: The impact and perception of hiya are highly situational.

- Evolving Concept: Influenced by modernization, globalization, and diaspora experiences, leading to shifts in expression and navigation.

- Understanding is Crucial: Essential for cultural sensitivity, effective cross-cultural communication, and building stronger relationships.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

- Is hiya the same as being shy or introverted?

While shyness or introversion can overlap with some manifestations of hiya (like hesitancy in speaking), they are distinct. Shyness is often considered a personality trait related to social anxiety, whereas hiya is a culturally conditioned socio-emotional response tied to specific social contexts, norms, and the preservation of face and harmony. A person who isn’t naturally shy might still feel strong hiya in certain Filipino social situations. - If hiya means avoiding conflict, how are disagreements handled in Filipino culture?

Disagreements are often handled indirectly to minimize confrontation and preserve pakikisama. This might involve using intermediaries (tulay), employing euphemisms or vague language, allowing time to cool down, or focusing on finding common ground. Direct confrontation is generally avoided unless absolutely necessary, and even then, efforts are made to manage potential loss of face (mukha). - Is hiya always a negative thing that Filipinos should try to overcome?

No, hiya is not inherently negative. As discussed, it has positive functions like promoting respect, politeness, and social harmony. The goal isn’t necessarily to eliminate hiya, but to understand its influence and develop the awareness (and perhaps assertiveness skills) to navigate situations where excessive hiya might be detrimental (e.g., preventing someone from asking for essential help or speaking out against injustice). It’s about balance and context. - How does hiya affect Filipinos working in Western business environments?

It can present challenges. The emphasis on indirect communication, reluctance to self-promote, and hesitancy to disagree openly (due to hiya) can be misinterpreted in environments valuing directness and individual assertiveness. Filipinos may need to consciously adapt their communication style, while non-Filipino colleagues benefit from understanding the cultural roots of these behaviors to foster better cross-cultural communication and avoid misjudgments. - Are younger Filipinos really less affected by hiya?

Evidence suggests a potential shift, but not necessarily a complete disappearance. Younger generations, particularly those in urban areas or with significant exposure to global culture, might express hiya differently or feel it less intensely in certain situations (like classroom participation). However, the underlying sensitivity to social context and the importance of Filipino values like pakikisama often remain influential, meaning hiya likely still plays a role, albeit perhaps a modified one. - What’s the difference between hiya and amor propio?

They are related but distinct concepts. Hiya is the feeling of propriety/shame/sensitivity itself. Amor propio is closer to self-esteem or sense of personal dignity. It’s the value placed on one’s own honor and status. An action that causes hiya (shame/embarrassment) is often damaging to one’s amor propio. So, hiya can be seen as the feeling triggered by a perceived threat to one’s amor propio or social face (mukha).

Sources:

- Enriquez, Virgilio G. (1994). From Colonial to Liberation Psychology: The Philippine Experience. De La Salle University Press. (Seminal work on Filipino Psychology, including concepts like Kapwa and Pakikiramdam)

- Pe-Pua, Rogelia, & Protacio-Marcelino, Elizabeth. (2000). Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino Psychology): A legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian Journal of Social Psychology,1 3(1), 49-71. (Overview of key concepts in Filipino Psychology)

- Lynch, Frank. (1962). Philippine Values II: Social Acceptance. Philippine Studies, 10(1), 82-99. (Early influential work discussing Smooth Interpersonal Relations and Hiya)

- Tan, Michael L. (Various Columns/Articles). Pinoy Kasi articles often touch upon Filipino cultural traits and values. (While specific articles vary, Tan frequently discusses cultural nuances).

- Pertierra, Raul. (Various Works). Anthropological studies on Filipino culture and social life often implicitly or explicitly discuss manifestations of concepts like hiya. (General reference to anthropological perspectives)

- Online forums and blogs discussing Filipino culture and diaspora experiences (e.g., discussions on platforms like Reddit’s r/Philippines, Filipino community websites). (Anecdotal sources reflecting contemporary experiences)